Whatever their views on Brexit, all politicians claim to want to deliver a country in which opportunities are spread more equally.

But the Education Policy Institute’s recent annual report shows that the most important measure of social mobility – the gap in educational attainment between poor children and the rest – is no longer closing. After years of progress, we are now at serious risk of going backwards.

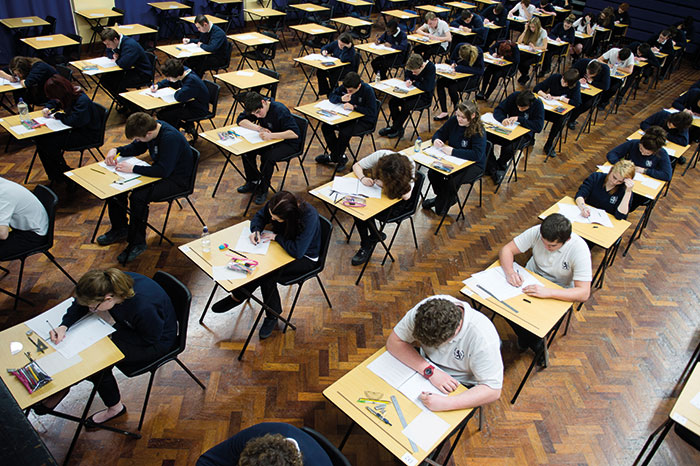

By the time they take their GCSEs, the poorest quarter of children are on average one and a half years of learning behind the others.

In the worst-performing parts of England – Blackpool, Peterborough, Rotherham – this attainment gap is as wide as two years. And for the most persistently poor children, it is also two full years.

We know that children who grow up in poverty suffer multiple disadvantages – many in the home. Indeed, 40% of the attainment gap at age 16 is already present at the beginning of schooling.

However, we also know that there is no iron law dictating that poverty must determine life chances – indeed, in some parts of England, the gap at age 16 is only six months, not 18.

During the past two decades, governments of all parties have used a variety of policy tools to try to close these gaps.

'Real-terms per-pupil funding for schools has fallen by 8% since 2010, while the proportion of local authority secondary schools in deficit quadrupled between 2014 and 2017-2018, with a third of such schools being in the red.'

New Labour introduced sponsored academies, the London Challenge and Sure Start centres. Under the coalition government, interventions included the pupil premium and extra early years support for disadvantaged two-year-olds. While it is not possible to precisely gauge the impact of these policies, we do know that the attainment gap over this period had been shrinking.

In 2015, EPI research indicated that the gap at age 16 would be closed within 50 years if trends continued. But in each subsequent year, the momentum has quickly drained away. The most recent projections make for very uncomfortable reading – indicating that poorer pupils will not draw level with their peers for over 500 years.

What explains this huge regression? We don’t know for certain. It could be that the pace of school improvement in the most challenging areas is not being maintained. Or the squeeze on school and local authority budgets could be playing a role.

Real-terms per-pupil funding for schools has fallen by 8% since 2010, while the proportion of local authority secondary schools in deficit quadrupled between 2014 and 2017-2018, with a third of such schools being in the red.

The new prime minister has been quick to acknowledge pressures. With much fanfare, he unveiled plans to “level up” school funding, addressing alleged imbalances in per pupil funding. But, while funding boosts may seem welcome, they are unlikely to end the current social mobility standstill.

Analysis shows that, under these plans, additional funding would in fact be disproportionately directed towards more affluent schools. On average, poorer pupils would attract less than half (£56) the additional funding of non-disadvantaged pupils (£116).

The PM may have overlooked the fact that a narrower schools funding gap may result in a bigger ‘opportunity gap’.

Policymakers are understandably preoccupied by Brexit.

But if leaders fail to pay attention to spreading educational opportunities, we may find that progress on social mobility falls into reverse gear, and that we become a country in which opportunity, and not just income and wealth, is spread less equally.