For those who would listen, alarms bells have been ringing over the past few months, sounding a warning that councils have been dipping dangerously into their rainy day savings.

The Institute for Government and CIPFA, in their Performance Tracker report last October, urged central government to “pay attention to any signs that local authorities are running down their reserves to plug gaps in day-to-day spending”.

Any council that was spending its reserves on “regular activity would soon find themselves in significant financial distress”, the tracker warned.

It seemed it wouldn’t be long before one fell. Then, on 2 February this year, Northamptonshire was compelled to issue a section 114 notice – the first of its kind in 20 years.

The section 151 officer took action and issued the notice, warning that the council had spent its reserves and would not be able to produce a balanced budget this year. Spending on all but safeguarding vulnerable people and statutory services was stopped.

Section 114 notices were introduced by the Local Government Finance Act 1988 and, after a few were issued in the 1990s, councils have balanced their books.

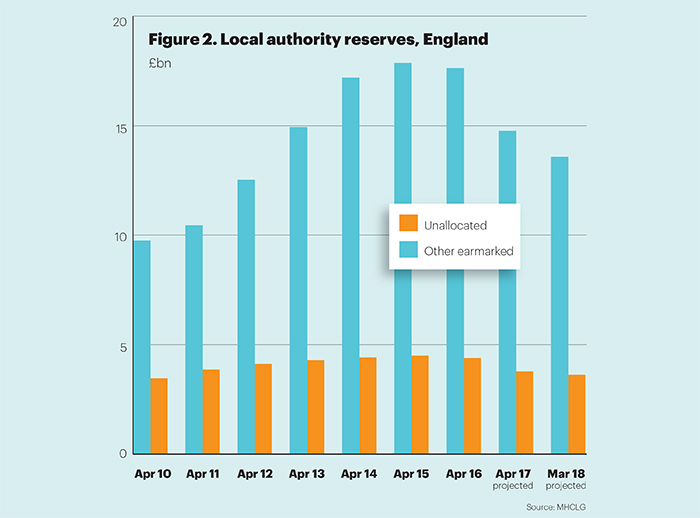

Indeed, since 2010 councils have been steadily building up reserves (see graph below).

Former local government secretary Sir Eric Pickles famously criticised councils in 2013, accusing them of “hoarding billions” while “pleading poverty and raising council tax”.

But 2016-17 government figures and those projected for 2017-18 show councils in England have started to dip into unallocated and earmarked reserves. Ringfenced reserves, such as those for public health and schools, cannot be used for other purposes.

On 1 April 2016, total unallocated and earmarked reserves for English councils stood at £22bn and, by the end of the financial year, had fallen to £21bn. By the end of the current financial year (2017-18), they are projected to have dipped to £17.2bn – a reduction of 18%.

The National Audit Office plans to release a report on Thursday this week on the financial sustainability of local councils in England, which is expected to highlight concern over the use of reserves.

Report author Aileen Murphie, director of local government value for money at the NAO, tells PF: “The sector is under increasing financial pressure. There’s a lot of uncertainty. It’s hard for an individual authority to see what their financial future might be without seeing what effect the new [local government finance] systems might have.

“The concern is that, if local authorities are continually dipping into their reserves, particularly to cover regular ongoing spending, it’s not a position that can carry on indefinitely.”

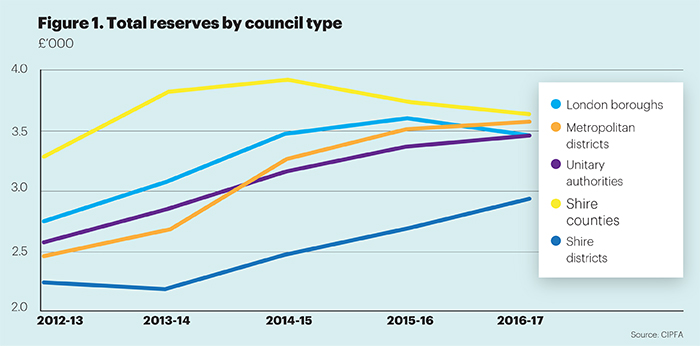

A closer look at 2016-17 figures (below) reveals which types of councils have been spending their savings. These are mainly county councils and London boroughs; others, particularly districts, have managed to continue to build them.

John Fuller, chair of the District Councils Network, offers an explanation as to why lower tier authorities have been able to add to their reserves. “The increases are associated with development and the recent uptick in planning permissions,” he says.

Councils responsible for planning – like districts – receive money from developers through section 106 agreements and community infrastructure levies, Fuller says.

Simon Edwards, director of the County Councils Network, echoes this, suggesting “lower tier councils have been in a position to add £400m to their reserves” in the past two years “arguably because of incentive-based funding, such as the new homes bonus”.

Fuller states districts have had to increase reserves to “offset the increase and transfer [of responsibilities] from central to local government”. The government could not pass on “onerous responsibility”, such as delivering Local Plans and appeals on business rates, without expecting councils to “build reserves to forward fund”, he tells PF.

Paul Dossett, head of local government at Grant Thornton, observes “district councils are, in some cases, still able to add to their reserves” because they are “not struggling with the demand-led pressures” on other councils, notably social care services for adults and children.

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government figures bear out that “demand-led” county councils have had to resort to raiding reserves. Northamptonshire is not alone.

“So long as local government spend continues to be cut it is inevitable more councils will approach a financial precipice."

Academic Tony Travers

Government figures show Surrey County Council’s reserves fell from £143.6m at the end of 2015-16 to £113.3m at the end of 2016-17 and are projected to drop to £72.2m next year.

It is well documented that Surrey has been struggling to fund adult social care and was considering suggesting a 15% council tax rise to residents in a referendum before the abandoning the plan. The council issued a statement saying: “We’ve agreed a three-year budget despite the severe financial pressure we – and councils across the country – are under due to rising demand for our services and falling government funding.”

Other counties that have also been dipping into reserves include Lancashire, going from £314.6m at the end of 2015-16 to £258.9m by March 2017, according to MHCLG figures.

Angie Ridgwell, Lancashire’s interim chief executive and director of resources, says the council’s revenue budget “has been supported in recent years by the reserves that have been available to the county council”.

She says there “will be sufficient funds within the transitional reserve to support the identified budget gap in 2018-19 and 2019-20”.

But she adds: “Further savings will need to be made and fully implemented by 2020-21 at the latest, to deliver a sustainable financial position going forward.”

Somerset’s reserves also went down from £56.9m on 31 March 2016 to £26.9m a year later. A Somerset County Council spokesperson told PF the figures were

in “no way a barometer of financial resilience”.

They pointed out their reserves went up in 2015-16 because of government funding for major engineering works related to floods in Somerset in 2014.

They went on: “[The] fall has been managed and [reserves] remain at a level considered adequate for an authority of this size and budget.”

At the CCN, Edwards says: “County authorities are facing a toxic cocktail of rising demand, historical underfunding of services, and core government grants reducing more sharply than other council types.

“It is against this backdrop and a projected £2.54bn funding black hole for counties by 2021 that many have had little choice but to draw down on reserves to protect frontline services.”

Local government expert and academic Tony Travers, a former member of the Audit Commission, comments that county councils have less budgetary freedom because “social care is such a large part of their spending”. They “clearly have no choice” but to start spending reserves, he tells PF, and forecasts more section 114 notices in the future.

“So long as local government spend continues to be cut it is inevitable more councils will approach a financial precipice.

“And what happens to the services? Failure,” Travers predicts.

He suggests the scrapping of the Audit Commission, a process completed in 2015, may be a factor as individual local authority finances are no longer in the spotlight.

“Dipping reserve levels are the best indication we have that councils’ ability to manage spending reductions are reaching the end of the road.”

Emily Andrews, senior researcher at the IfG

Its abolition has been “enormously useful” to the government, says Travers, because, through its audit activity, it would have been reporting year-on-year on each council and could have warned if any were running into financial trouble.

It is not just counties that are feeling the strain. Figures also reveal that London councils are now spending more of their reserves. Even before the Grenfell Tower tragedy last year, it appeared Kensington & Chelsea had reduced its reserves from £235.6m in March 2016 to £163.1m in March 2017.

A RBKC spokesperson said: “The difference between the two financial years is that our balances for 2017 reflect planned capital expenditure – which was greater than the previous year.”

The government figures show the councils’ reserves were projected to be £199.4m at the end of this financial year, although, following the Grenfell Tower tragedy, in all likelihood that will be lower.

According to MHCLG figures, Westminster also spent just over £90m of its reserves between 2016-17 and 2017-18 – with levels dropping from £275.2m to £185.1m.

However, a Westminster spokesperson tells PF this is because of a “technical [accounting] adjustment”. If the provision set aside for appeals against business rates is taken out of the equation (the business rates safety net payments), it actually saw reserves grow by £16m during 2016-17, they explain.

To the south of the capital, Croydon’s reserves went from just £41.3m at the end of 2015-16 to £32.8m in 2017-18, although estimated figures show it should have built them up again to £43.2m next year.

A council spokesperson highlights major cuts to grant.

“Croydon continues to lobby central government for fair funding and, despite facing the same pressures as an inner London borough, we are geographically an outer London borough and therefore only receive outer London funding, which is considerably less,” they say.

London Councils tells PF that boroughs had “prudently added to reserves” in the early years of austerity as more heavily grant-dependent urban areas were facing the steepest cuts in central government funding.

A spokesperson explains that, since 2015-16, boroughs have been drawing on reserves to support wider transformation programmes.

“Earmarked reserves are planned to continue to reduce significantly in the next three years,” they add.

“Clearly, this is not sustainable in the longer term in the face of continued funding reductions and growing demand.”

Dossett says London boroughs are having to dip into reserves because of “significant pressure on social care, particularly in respect to looked-after children, as well as a major spike in homelessness and the nil recourse to public funds”.

Of course, such pressures on councils are not going to go away any time soon.

Emily Andrews, senior researcher at the IfG, paints a bleak picture: “Northamptonshire’s situation is just the latest example of the wider pattern across public services we uncovered in our Performance Tracker report.

“Dipping reserve levels are the best indication we have that councils’ ability to manage spending reductions are reaching the end of the road.”

She suggests Whitehall gather better data – on service levels as well as spending – to understand what kind of efficiency plans will be achievable going forward.

“Without it, they risk more expensive emergency actions, and loss of services to the citizen,” she warns.

Jo Pitt, CIPFA’s local government policy manager, believes “unless the government creates a sustainable funding plan for local authorities it is likely that reserves will increasingly be used to plug short-term gaps in finances.”

She warns: ‘Reserves are there to safeguard councils against future risk, not to alleviate short-term funding pressures or to avoid making cuts to service delivery.”

An MHCLG spokesman tells PF: “Overall, councils will see a real-terms increase in resources over the next two years, more freedom and fairness and with a greater certainty to plan and secure value for money.”

Councils are “free to determine the level of reserves they hold and are accountable to their electorate for the decisions they make”, the department says.

“We are clear all councils should keep sufficient sums of money in reserve so that they have a financial cushion to meet sudden unexpected costs.”

However, it can be hard for councils to determine what “sufficient sums” of reserves means for them.

Dossett optimistically points out councils should not run out of cash because they can borrow funds from the Public Works Loan Board and from other local authorities. The government is also likely to step in if services fail, he believes.

Solace President Jo Miller is gloomier. She says councils are now “facing a cliff edge with no idea what funding they will have after 2020”.

“Reserves are classic ‘rock and a hard place’ territory” that “provide a cushion at best”. She points out: “There are no easy answers.”

Especially if, as Travers suggests, England has a “bigger public sector than the taxpayers want to pay for”.

“Councils have to balance a judgment about how much insurance they might need against future shocks with the risk of not being able to meet the needs of vulnerable people now,” Miller tells PF.

It is now, she says, “urgent that we turn our collective focus to securing a sustainable funding base for local public services”.

A budget without balance

A section 114 notice is made when “in the course of the discharge of functions of the authority, the executive or a person on behalf of the executive” is about to or has made a decision or taken action “incurring expenditure which is unlawful”.

So says the Local Government Finance Act 1988.

“Unlawful” is not achieving a balanced budget and taking a local authority’s finances into the red.

However, CIPFA’s briefing Balancing Local Authority Budgets explains just how hard it is to determine what “balanced” means.

“What is meant by ‘balanced’ is not defined in law and this has meant CFOs using their professional judgment to ensure that the local authority’s budget is robust and sustainable,” the document, published in March 2016, states.

“A prudent definition of a sustainable balanced budget for local government would be a financial plan based on sound assumptions,” CIPFA suggests.

It warns that section 114 notices should only be issued in the “gravest of circumstances” and “should be seen as the action of last resort”.

It adds: “While issuing a section 114 notice should not be seen as a failure, it will result in the loss of financial control by the leadership team.”

Warning given in Scotland

Scotland appears to be ahead of England in identifying the issue of councils increasingly using their reserves.

In November last year, the Accounts Commission issued a warning that “some councils risk running out of general fund reserves within two to three years”.

The watchdog named Moray, Clackmannanshire and North Ayrshire as councils that were in danger of using up cash reserves within three years if they continued to use them at the levels planned for 2017-18.

Scottish councils were “finding it increasingly difficult to identify and deliver savings and more have drawn on reserves than in previous years to fund change programmes and routine service delivery”, the commission recorded in its annual financial overview.

Debt for Scottish local authorities had increased by £836m in 2016-17 as councils took advantage of low interest rates to borrow more to invest in larger capital programmes, it noted.

Graham Sharp, the Accounts Commission chair, said at the time: “Effective leadership and financial management is becoming increasingly critical and medium-term financial strategies and well thought out savings plans are key to financial resilience and sustainability.”

Image credit: Getty