Selective schools are firmly back on the agenda. Yet while the government’s decision to push ahead with the expansion of grammars has incited much controversy, to many it probably didn’t come as a surprise.

Following the appointment of Damian Hinds to Secretary of State earlier in the year, a revival of the Prime Minister’s plans in the government’s much delayed Schools that work for everyone consultation was expected – albeit in far more limited form.

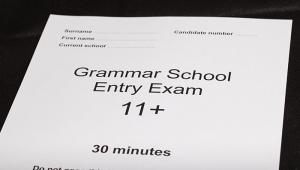

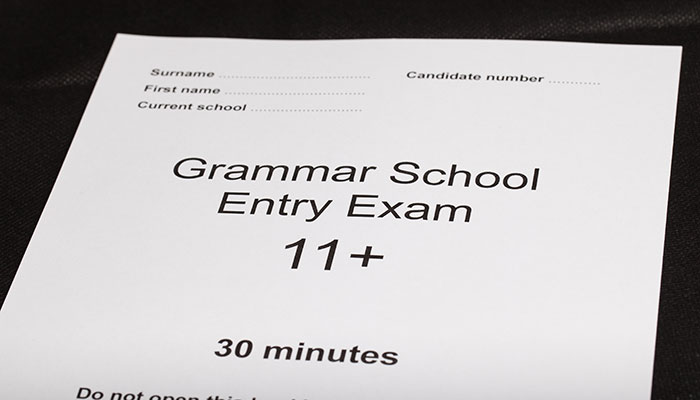

The recently announced Selective Schools Expansion Fund includes £50m to increase the number of places at existing grammar schools. Schools granted extra funding will be required to form a “fair access and partnership plan”, which compels them to outline how they will boost the number of places offered to pupils from poorer backgrounds.

However, while these new proposals are certainly more modest and conciliatory than the pre-election plans, the evidence tells us that they are still unlikely to improve social mobility.

Shortly after the government’s original plans were revealed, the Education Policy Institute published one of the largest studies into the impact of grammar schools on social mobility.

Our research found that as the number of grammar school places increases in areas where they are already highly concentrated, an attainment penalty emerges for pupils in the local area who don’t get in. As you might expect, pupils missing out are disproportionately derived from disadvantaged backgrounds.

So while Hinds’ plans may be well-intentioned, and may indeed benefit some less well-off pupils, overall they are likely to exacerbate educational disadvantage in targeted areas.

What’s more, in addition to penalising pupils who do not get in to grammars, we know that selective schools have a limited impact on the overall attainment of pupils in England, once a pupil’s prior attainment and socio-economic background is taken into consideration.

Inequality in England’s education system is still a huge problem. The gap in attainment at school between poorer pupils and their better-off peers is substantial and, based on the current rate of progress, is unlikely to be bridged for decades.

The government aims to help poorer pupils with its new grammar school plans. The evidence suggests they will further entrench educational inequality

This gap is narrow at the beginning of a child’s life, and widens over time through the school system. By the age of 11, the age at which selection for grammar schools takes place, as much as 60% of this gap is already apparent. Accordingly, it is likely that interventions at age 11 are far too late to spark considerable progress.

Given all of the available evidence, it is clear that there are far more effective ways to advance the prospects of disadvantaged pupils than directing increasingly scarce funds into academically selective schools.

Firstly, given what we know about the disadvantage gap increasing over the course of a child’s time at school, the government would be better off targeting resources towards early education.

Secondly, an effective strategy could be to strengthen the number of high-quality non-selective schools in under-performing areas – an approach with a proven track record in London over the past two decades. Presently, there are already about five times as many high-quality, non-selective schools than there are selective schools.

Evidence produced by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), after scrutinising diverse education systems in developed countries over a number of years, concludes that leading nations achieve both high performance and equity in schools through policies that avoid selection and segregation.

If the government is serious about improving the life chances of those from poorer backgrounds, and reducing levels of educational disadvantage, it should heed the OECD's message – and swiftly reconsider its plans for grammar schools.