After eight years of relentlessly plucking low-hanging fruit, it is time for the government to have an honest conversation about the true cost of public services.

That was the conclusion of the Institute for Government and CIPFA’s annual public services Performance Tracker report, published in October.

Since former chancellor George Osborne delivered his emergency budget in June 2010, claiming the government had “laid the foundations for a more prosperous future,” public services have been through a rigorous process of streamlining, but CIPFA and IfG’s research argues that further efficiency savings may prove hard to come by.

Discussing the report’s findings at an IfG event, Emily Andrews, associate director at the think-tank, said that, while public services have become more efficient, “we are reaching the end of the road for efficiency savings”.

Streamlining has been effective in seven out of the nine public services analysed by CIPFA and IfG (box below) but “demand is set to grow in almost all these services”, Andrews claimed.

Nine services examined by CIPFA and the IfG in the tracker

- General practice

- Hospitals

- Adult social care

- Children’s social care

- Schools

- Police

- Criminal courts

- Prisons

- Neighbourhood services

Efficiency has been achieved largely as a result of the public sector pay cap, which has kept the wage bill down. But this year the government loosened the cap with pay rises of between 1.5% and 3.5% for the police, prison officers, doctors, nurses and teachers.

The time has come “to be explicit about the cost of public services – vague promises about the end of austerity are not productive,” Andrews argued.

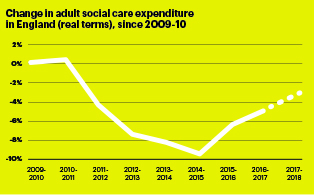

Adult social care is one area expected to come under the greatest pressure, and the Local Government Association has identified a £3.5bn funding gap by 2025 (see graph, below, for changes in expenditure).

CIPFA’s report said the adult social care sector is propped up by an “increased reliance on informal care,” from family and friends of those in need.

A separate study from Carers UK in October found unpaid carers contribute £132bn worth of care support annually. This, the tracker noted, is evidence of the government “quietly shifting the costs of services onto individuals”.

This trend is also apparent in the UK justice system, where legal aid cuts have meant more defendants now have to pay for their own defence – or even defend themselves. Criminal legal aid spending fell by 32.1% in real terms between 2010-11 and 2017-18, from £1,175m to £891m in 2017-18.

This trend is also apparent in the UK justice system, where legal aid cuts have meant more defendants now have to pay for their own defence – or even defend themselves. Criminal legal aid spending fell by 32.1% in real terms between 2010-11 and 2017-18, from £1,175m to £891m in 2017-18.

Prisons are the only area where spending cuts have not been counter-balanced by efficiency improvements, according to the research.

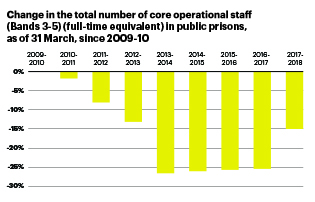

Andrews noted the Ministry of Justice is “one of the few unprotected departments” and, as such, has had to manage spending cuts through staff reductions.

And despite increasing the amount of prison staff by 3,205 since March 2017, the aftermath of sustained cuts has meant an initial reduction in staff levels has left an experience gap in the sector, with 33% of prison officers having less than two years’ experience in 2018, compared with 7% in 2010. Cuts have manifested in increases in assaults on prison staff, with the number of attacks on staff almost tripling to 9,000 between 2009-10 and 2017-18 (see graph, below right).

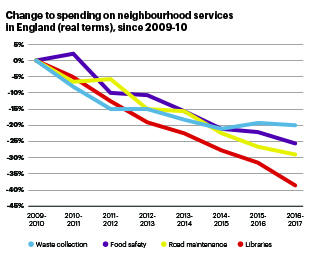

Elsewhere, neighbourhood services have sustained the biggest cuts of all the nine services considered in the report. The number of authorities charging for garden waste collection rose from 88 to 199 between 2010-11 and 2018-18, reinforcing the idea articulated in the report that “where government can get people to pay directly for services, it is often doing so”.

Over the same period, the number of authorities offering free garden waste collection fell from 236 to 137, according to the tracker (see graph, below left).

“We are now doing less and people are paying more for it,” commented former CIPFA president Andrew Burns, who also spoke at the event.

Burns, who is director of finance and resources at Staffordshire County Council, raised the issue of disproportionate spending on certain services, specifically social care. He said: “In Staffordshire, we now spend 70% of our budget on 2% of our population,” underscoring the report’s claim that, locally, spending on social care has squeezed other services.

Burns, who is director of finance and resources at Staffordshire County Council, raised the issue of disproportionate spending on certain services, specifically social care. He said: “In Staffordshire, we now spend 70% of our budget on 2% of our population,” underscoring the report’s claim that, locally, spending on social care has squeezed other services.

The report found that non-social care spending now makes up only 46% of all local government spending, down from 55% in 2010-11 – a trend that CIPFA and IfG said “creates obvious potential for public resentment”.

“People paying local taxes think that they are paying for services available to everyone in the area, such as waste collection and libraries. But those universal services are being squeezed by social care, used only by a minority,” the report said.

Burns also alluded to the adult social care precept, which came into effect in April 2018 and allows councils that provide social care to adults to increase their share of council tax by up to an extra 3%. He said: “There has been a shift from national to local taxation to fund social care, but this shift is not the solution.”

With central government funding for local authorities falling by 49.1% between 2010 and 2018, according to the National Audit Office, councils have had to think of creative ways to bolster their finances.

“Councils are increasingly looking at income generation, but that is only a marginal contribution,” Burns said.

The Performance Tracker highlighted the fact that “trade-offs” were necessary within public services if the government fails to increase taxes.

“It is clear that demographic pressures and other trends will prove unsustainable without a significant change in the scope or nature of public services, a change in the degree to which people pay directly for those services, or a much higher level of taxation,” the report said.

“It is clear that demographic pressures and other trends will prove unsustainable without a significant change in the scope or nature of public services, a change in the degree to which people pay directly for those services, or a much higher level of taxation,” the report said.

Polling conducted by Ipsos Mori on behalf of Deloitte recently found that 62% of people in the UK would be open to higher taxes to support increased public spending – up from 40% in 2009. But when this notion was put to the panel, panellists agreed that, in reality, increasing tax would be difficult.

However, CIPFA and IfG’s report notes that “tough decisions will have to be made: whether tax increases, or lower expectations of services, or more individual contributions, or radical service changes”. The government needs to be explicit about the realities, it says.

“They need to begin telling people clearly that they face a national choice.”