By Mark Hellowell | 26 September 2013

The government's National Infrastructure Plan promises much, but can it deliver? With HS2 under fire, private finance at a premium and only a handful of pipeline projects completed, it will be a big ask

If its current rhetoric is to be believed, the government is embarking on the biggest programme of infrastructure development since the Victorian era. The International Monetary Fund, the Labour Party and numerous experts say otherwise, but ministers have a £42bn High Speed 2 railway plan – commanding the ‘passionate support’ of both David Cameron and George Osborne – to silence all criticism.

The scheme is controversial, for sure, but it serves an important political purpose: that of providing a degree of substance to an otherwise contestable claim to be investing in the economy. After all, if the government is willing to support so controversial a project, on the basis of what the chair of the Public Accounts Committee Margaret Hodge describes as ‘fragile numbers, out-of-date data and assumptions that do not reflect real life’, who could accuse ministers of not taking infrastructure investment seriously?

Yet the critics have a point, as will become more evident in the Autumn Statement later this year, when the Treasury is forced to report slow progress on the National Infrastructure Plan. In reality, investment remains muted, in both the public and the private sectors. Despite Chief Secretary to the Treasury Danny Alexander’s claim in the July Spending Round that the government is implementing the ‘most comprehensive, ambitious and long-lasting capital investment plans ever’, the figures reveal a 1.7% fall in public capital spending. Even the much-trumpeted £300bn of investment means a real-terms fall in capital spending in every year from 2015/16.

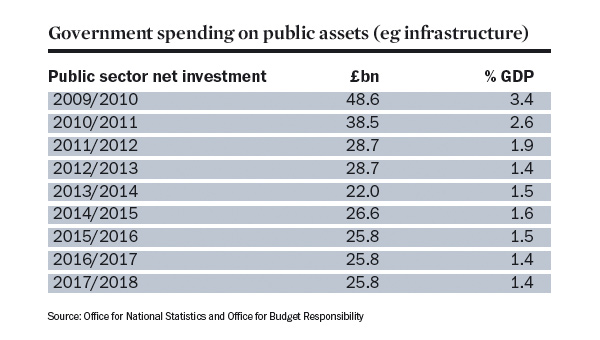

Overall, gross public investment in today’s money will be £450bn in the 10 years to 2020/21, compared to £530bn in the previous decade, if the capital value of Private Finance Initiative projects is included. Even as a percentage of overall government spending, the coalition’s record is unimpressive. Despite the hatchet taken to revenue spending since May 2010, gross investment is projected to average about 6.2% of total spending over the decade, compared to 7.6% (including PFI) in the previous ten years. Recent figures for net investment, which is recognised as the most accurate indicator of how much the government is adding to the public asset base, show it fell from £49bn in 2009/2010 to £29bn in 2010/2011, and this is forecast to fall to £26bn – just 1.4% of GDP – by 2016/2017 (see chart).

There has been no lack of activity, but the gap between aspirations and outcomes is stark. The NIP specifies 40 priority projects – from the Northern Line extension of the London Underground (on which creditors have received a £1bn government guarantee), to Crossrail, to the building of offshore wind farms and High Speed Rail 2 – but progress has been slow at best, as an update on the NIP in March had to acknowledge. And the problems spread to social infrastructure, too. After a series of delays, work has at last started under the Priority School Building Programme, the government’s largest school-construction project, but there have been a series of changes since it was originally envisaged, including a decision to directly fund £1bn of work originally slated to be delivered under Private Finance 2.

Similar decisions were made to directly fund a large new Ministry of Defence accommodation programme and the Crossrail rolling stock, apparently due to ministerial concern that the PF2 concept had not been proved and delays were likely. And in prisons, the government has announced details of ‘a new approach’ to completion based on the construction of new prison capacity, including a possible new 2,000place super-prison and four new house blocks at existing prisons. But it is unclear whether PF2 – or some other form of private finance – will be required to deliver it.

Perhaps the bigger challenge is in the private sector, where 60% of Britain’s infrastructure investment needs actually reside. Official figures show that only seven out of 576 projects in the government’s infrastructure pipeline – most of which relate to utilities in private sector ownership, and require financing in the equity and debt markets – have been completed. While the economy has been crying out for infrastructure spending (as the respectable face of economic stimulus) since 2010, only 20% of these have yet to start construction.

According to the influential World Economic Forum report on global competitiveness, Britain has fallen from 24th to 28th in the world for the quality of its infrastructure. While it is difficult to see which events over the past 12 months actually merit such a league table collapse, the fact that the world’s seventh-largest economy is perceived to have worse infrastructure than South Korea, Malaysia and the Bahamas is a valid cause for political attention. A cacophony of voices is calling for something to be done, and there is an increasingly prominent view that some form of independent office is required – a body that can, to a degree, take the inevitable volatility of politics out of national infrastructure planning and delivery.

The idea was introduced in the summer in a report by the London School of Economics Growth Commission, a mixture of academics and industry grandees, which called for the establishment of a statutory Infrastructure Strategy Board. The aim was to provide independent, expert advice on infrastructure to parliament, and to lay the foundation for cross-party consensus on long-term investment policy. The idea is much the same as that of the Labour-commissioned review by Sir John Armitt, former chair of the Olympic Delivery Authority, whose 32-page report was published earlier this month and received relatively little media attention.

Although an aide to the shadow chancellor refers to the Armitt review as the ‘last word in Labour Party infrastructure policy’, the report does no more than echo the Growth Commission’s call for an independent body. Doubtless the appointment of Armitt, fresh from the success of the Olympics, was politically expedient for Labour – not least because the coalition had recently made Lord Deighton, former chief executive of the ODA, a minister for infrastructure in the Treasury – but his report fails to address a key variable in the investment problem: the chronic lack of finance.

There is a vigorous debate about why this problem still remains half a decade after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. A forthcoming paper by the influential Oxford University economist Dieter Helm suggests that the problem is down to excessive political and market risk. Governments can’t be trusted to make good on their promises to give investors a reasonable return, and the lack of a joined-up approach to infrastructure investment means investors are uncertain as to whether the £250bn of investment envisaged in the national infrastructure plan will be affordable to consumers. In a country where perhaps a quarter of households are likely to be ‘fuel poor’ within a couple of years, the affordability of additional costs from renewables and nuclear is uncertain.

As the National Audit Office pointed out in February, there has been no overall assessment of the impact of infrastructure spending on consumers. (Infrastructure UK was tasked with doing this precise thing in 2012, but dropped the assignment due to its being technically too difficult.) To the extent that affordability has been assessed by the government at all, this has been done on a sector-by-sector basis.

According to Helm, the conclusion any lender will come to is that the NIP is not founded on a secure revenue base. ‘No amount of trips to China to ask lenders to cough up will solve this,’ he observes.

No doubt market risk is a factor, but there are significant constraints on the market, too, which are ultimately traceable to the regulatory response to the financial crisis. Stricter capital adequacy regulations under the Basel III Accord make long-term lending costly for commercial banks. These regulations, under the control of the Bank of International Settlements, seek to ensure that banks’ long-term capital is sufficient to support the risks on their assets. Basel III raises required capital ratios incrementally from 8% in 2013 to 10.5% in 2018, and banks are responding by reducing risk-weighted assets rather than increasing equity.

One way of doing this is to reduce lending into sectors such as infrastructure, which, because of long maturities, are expensive in capital adequacy terms.

The government’s response has been to encourage alternative investors, particular pension funds, to step into the market recently exited by banks. However, UK pension funds have historically invested relatively small amounts in infrastructure assets. Pension funds in Britain invest an estimated 1% of their total assets in infrastructure, which is low by international standards (the figure is up to 15% in Canada, for example). This is because most UK pension funds lack the capacity and in-house expertise to invest directly and assess risks.

The intention to tackle this lies behind the new Private Finance 2 model, the coalition’s successor to the much-maligned PFI, which has been restructured to offer a lower risk profile to less-savvy and more risk-averse funders. More generally, the government has established the Pensions Infrastructure Platform, which includes the National Association of Pension Funds, and which represents around £800bn of assets; the Pension Protection Fund, with over £6bn; and a group of smaller funds holding a combined £50bn; and is expected to make its initial £2bn investment in infrastructure projects later this year. The PIP has a ten-year target of raising an additional £20bn in infrastructure investment.

But progress has been too slow, and the plan continues to face serious headwinds. Increasingly, these investors are – like banks – constrained by international regulations. The Solvency II protocol, which codifies long-standing European Union directives on the insurance industry, introduces a minimum capital requirement for insurance firms, and similar principles are due to be adopted by pension fund regulators following a review of the EU Pension Funds Directive. Recent analysis by the ratings agency Fitch suggests that anything less than a single-A rating for infrastructure assets would be uneconomic for investors. Such problems are unlikely to be answered by an independent office for infrastructure, as the Armitt review calls for, and all require a much more active role for the state.

In its distinctive way, the coalition government has acknowledged this. Its solution has been to make £40bn available in guarantees, with the aim of giving lenders greater comfort that they’ll get their money back. This approach is part of a wider coalition government motif of ‘off-balance sheet’ economic stimulus, similar to the ‘Help to Buy’ programme of mortgage guarantees. This has led to criticism from the IMF, which fears a reflating house-price bubble.

Unfortunately, perhaps, no such bubble is evident in infrastructure, and the approach has met with limited success. Just £1.6bn of the available guarantees have been taken up, as uncertainty about the future shape of infrastructure and the affordability of new investments for consumers remains. The reason, argues Paul Connolly, director of the Management Consultancies Association, is the lack of coordination in infrastructure strategy. ‘Investors simply cannot see an overall infrastructure strategy to buy into,’ he says, citing the ‘lack of buzz’ around guarantees and PF2 as the salient examples.

A more activist role for the state was envisaged by the outgoing Labour government, which began to draw up plans for a national infrastructure bank in 2009, which it believed could help to increase the supply of private finance. This idea was also backed by the LSE Growth Commission, which pointed out that such a bank could overcome regulatory constraints and reduce political risk. International experience appears to show the advantages of a bank with this sort of mandate, such as the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Germany’s Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Though the idea was backed by both Labour and Liberal Democrat manifestos for the 2010 election, and commands the support of the all the great and the good economists at LSE, the limited scope of the Armitt review appears to underline the fact that such radical measures are off the table, at least in the short term.

Part of the reticence originates in a fear that a dreaded ‘central state planner’ will re-emerge, lacking the information to allocate investment to the most beneficial projects and acting as a drag on growth. Such hesitancy is understandable, but in the longer term, it may not be sustainable.

But even as spending on public services is constrained and public capital investment is curtailed, the state is slowly, tentatively, creeping back into the infrastructure business. The old nationalised industries had their problems, but under state control, the country’s infrastructure coped with the most rapid period of economic growth in history, from the end of the Second World War until the 1970s. It is far from clear that a privatised economy can do likewise as Britain gradually drags itself from its current economic malaise.

Mark Hellowell is a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh and an advisor to the Treasury Select Committee

This feature was first published in the October edition of Public Finance magazine