By John Thornton | 1 November 2012

Why does Whitehall find it so hard to reap the benefits of shared services? One reason is that departments still put their individual needs first

When a former county treasurer recently told an audience of senior finance professionals: ‘Shared services do not work, or to be more specific, I have not seen a shared service arrangement deliver the planned savings’, he was greeted with a general murmur of agreement.

Later, a member of the audience did challenge this statement, saying his shared service project had been very successful. But the overriding view of those present seemed to be that shared services had over-promised and under-delivered. Why should this be?

The potential benefits are enormously persuasive. By sharing infrastructure and systems you can achieve substantial economies of scale. For each party it should build greater organisational capacity, ensure resilience and lever in more capital for investment. It should also provide a great mechanism for stimulating innovation and driving improvement.

There have, however, been some well-publicised failures. According to a recent National Audit Office report, plans for Whitehall departments to save money by sharing back-office services have cost £500m more than projected.

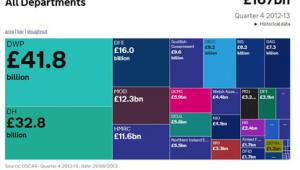

The NAO reviewed five of the eight shared services centres that were created across Whitehall following Sir Peter Gershon’s efficiency review in 2004. Together they were expected to cost £0.9bn to build and operate and then save £159m over the five years to 2010/11.

To date, they have cost £1.4bn. Only one, at the Ministry of Justice, has achieved sufficient savings to cover its costs. Two others, for Research Councils UK and the Department for Transport, have each cost more than £100m to build, overspent by at least a third, and are unlikely to generate enough savings to ever recoup their setup costs.

Many of these shared services initiatives were predicated on and inspired by private sector models. IT company Oracle, for example, used shared services to cut its costs by over 25% and save $1bn. At the heart of the Oracle strategy was investment in technology, shared services and standardised processes. This included moving from 52 versions of Oracle’s financial systems to one and transferring most of its global transaction processing to a single shared service centre. It did this some years ago and since then has acquired numerous businesses, adding substantial revenues and business capability, and integrated these into its shared service centre without significantly increasing its core overheads.

Why has the public sector found it so difficult to achieve similar savings from shared services? The NAO report concludes that the services provided are usually overly customised and made more complex to meet the needs of individual departmental customers, resulting in multiple versions of systems and processes, thereby significantly reducing the ability of the shared service centres to make efficiencies.

Most departmental customers have not acted as ‘intelligent customers’, they have not driven savings and rationalisation. Government has not developed the necessary benchmarks against which it could measure performance and drive improvement. Plus, the use of the centres has been voluntary and so departments have struggled to roll out shared services fully across all their business units and arm’s-length bodies.

This does not prove that the concept was wrong but it does show that you cannot just lift a model from the private sector without considering the wider structural, cultural and policy levers. Shared services have worked in the private sector and parts of the public sector, usually within single organisations, with strong leadership that could force through standardisation, automation and rationalisation.

There remains a strong commitment to shared services across government departments – but have they learnt the lessons of the past?

John Thornton is the director of e-ssential Resources and an independent adviser on business transformation, financial management and innovation

This feature appeared in the November issue of Public Finance