After five years of cuts, adult social care spending is on the increase.

This has been made possible by new ring-fenced grants from central government, and thanks to councils raising more tax locally through the social care precept.

Our new research, published last week, with support from the IFS’s Local Government Finance and Devolution Consortium, finds that spending increased by 7% in real-terms between 2014–15 and 2017–18.

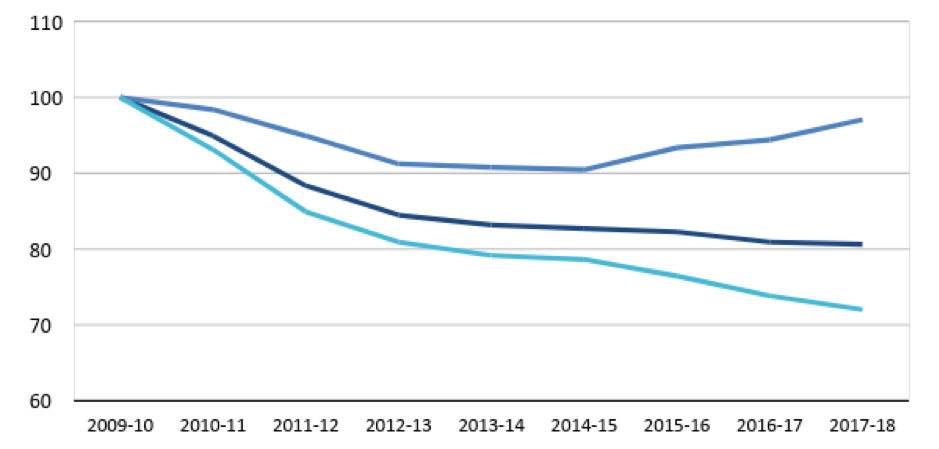

Service spending by councils in England (2009–10 = 100), 2017-18 prices

Source: Author’s calculations using MHCLG local government revenue expenditure and financing statistics (various years). More detail in the report.

Note: Service spending excludes spending on education, police, fire and public health. Includes spending funded by transfers from the NHS (i.e. the Better Care Fund).

Recent increases haven’t fully offset the 10% fall in adult social care spending that happened between 2009–10 and 2014–15.

Spending in 2017-18 on adult social care was budgeted to still be 3% lower than its 2009-10 peak.

As the population has grown over this period, this is equivalent to 9% lower spending per person.

The modest recovery in adult social care spending could continue in 2018-19 as ring-fenced funding is up by a further £830 million.

Depending on how councils choose to allocate their non-ring-fenced budget spending on adult social care this year could exceed its 2009-10 level – although it would still be lower per person.

These changes are taking place against a backdrop of much larger cuts to the rest of council spending.

Whilst adult social care was cut by 9% per person between 2009-10 and 2017-18, spending on other council services fell by an average of 32% per person

In part, this has been a choice by councils who have had to make difficult trade-offs given the pressures facing many of their services.

Indeed the extent to which councils have protected adult social care relative to other services has varied around the country reflecting different local challenges and priorities.

But councils have also been given a big steer by central government to prioritise social care.

When additional money has been made available to councils’ by central government, it has been on the condition that the funding be used to support social care services.

This applies to transfers from the NHS budget (the Better Care Fund), new grant funding (the Improved Better Care Fund) and the extra tax councils have been permitted to raise (the Social Care precept).

Councils could in principle reduce the spending on adult social care out of the non-ring-fenced portion of their budget (so that the new funding acts to reduce cuts elsewhere), but the upturn in adult social care spending since new grants came on stream does suggest that a lot of this money is being used as intended by Westminster.

Unless councils decide to circumvent the ring-fence, spending on other council services is set to continue its downwards trajectory over the next couple of years, as the pot of funding available to councils (that isn’t ring-fenced for social care) is still shrinking.

Delivering further cuts to services that have already been cut by almost a third (per person) on average will be difficult, especially with councils saying pressures are building in other areas like children's services and housing.

Beyond 2020, further challenges loom.

A fairly immediate issue is whether funding streams that have been introduced to support social care will continue after the end of the decade. For example, much of the increase in adult social care spending has been funded by the social care precept (allowing councils to increase council tax by an extra 3% per year).

Although council tax rates will remain permanently higher, it remains to be seen whether councils’ will be allowed to keep making big year-on-year increases to fund spending growth.

Looking to the longer term, previous IFS research has shown that even if council tax bills were to go up substantially, income from council tax and business rates is unlikely to keep pace with rising demand for adult social care over the next 20 years.

This means that additional funding (either grants or more devolved tax revenues) would be needed if we want to avoid paring back social care provision, or making yet more cuts to other council services.

That’s before we even start thinking about increasing the generosity of the care system.

The sustainability of adult social care funding in the future will depend on the outcome of three things the government has control over: the social care green paper, the Fair Funding Review, and the next Spending Review.

All three are important as adult social care funding, local government funding, and overall plans for public spending are intimately linked.

But sustainability will also depend on something it that the government has much less control over – the performance of the economy and public finances.

The outlook for local government generally, and adult social care specifically, is therefore likely to remain challenging and uncertain.