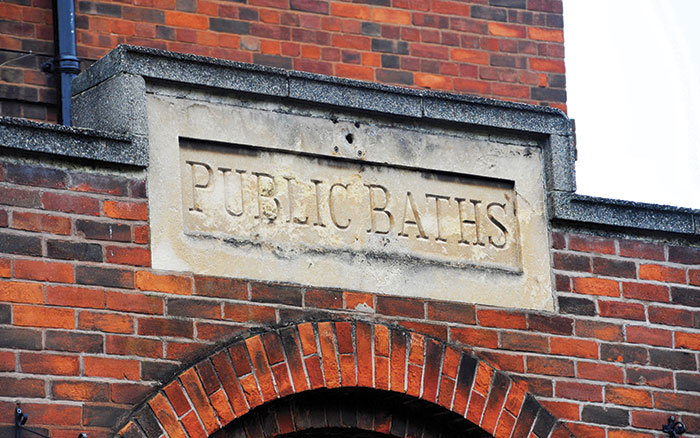

Local authorities own vast amounts of land and buildings, from large headquarters to public toilets and everything in between.

The stock is diverse and in some cases will have been built up over a substantial period, with some dating back to the 19th century.

Information on these buildings needs to be kept up to date, for both maintenance and compliance requirements.

From the day of completion, a building starts to deteriorate.

The rate of deterioration will depend on various factors, including the quality of materials, the frequency and volume of use, the environment and the quality of the maintenance regime.

The performance of buildings from a maintenance and compliance perspective should be reviewed on a regular basis.

The performance of buildings from a maintenance and compliance perspective should be reviewed on a regular basis.

Following research with councils, CIPFA has found that over 45% have not conducted a recent condition survey, with only 17% having undertaken surveys on a rolling basis of 20% or more of their estate per year, which is considered good practice.

In the UK, most public bodies categorise the condition of a building for its use as follows:

A: Good – performing as intended and operating efficiently

B: Satisfactory – performing as intended but showing minor deterioration

C: Poor – showing major defects and/or not operating as intended

D: Bad – life expired and/or serious risk of imminent failure.

Condition is usually assessed by site surveys.

It is recommended that authorities assess 20% of their buildings each year so, over five years, they have a complete picture of the estate.

This has several advantages:

● It provides clear, non-technical information to politicians and officers on the estate’s condition and the effects of expenditure

● Change is tracked over time

● Condition information is easily accessible

● It enables maintenance expenditure to be prioritised

● It allows policy in asset management standards to be set out (i.e. “If we can’t achieve all A grade buildings, let’s aim for a B” or “Let’s have publicly accessible spaces as A and back office as B”).

Works required are generally divided into three priority bands:

1: Urgent works to prevent immediate closure of the premises and/or to address an immediate high health and safety risk

2: Essential work within two years to prevent serious deterioration

3: Desirable work to be done within three to five years.

This approach has significant benefits.

It enables asset managers to prioritise maintenance, while allowing them to argue their case for maintenance budgets based on need.

It also allows for lifecycle planning of maintenance.

In addtion, this approach shows the effects of policy in setting standards and supports option appraisals for future use or disposal.

Generally, CIPFA has seen a drop in returns for condition and maintenance indicators, so this information is going out of date.

This can cause problems, not least because it means there will be less confidence in property data, which reduces the ability to make evidence-based arguments for adequate property maintenance spend.

Post Grenfell, all public sector bodies need to have a good understanding of the maintenance needs and the health and safety issues around their properties.

In addition, tracking year-on-year performance and the effects of maintenance spend and estate policy on overall maintenance need will become more difficult.

This means option appraisals may be conducted without the full picture.

Maintenance expenditure is squeezed.

The average percentage of priority 1 maintenance works has risen by 30% over the past year, and spend as a percentage of maintenance need came in at just under 17%, a similar drop from the average of the previous three years.

Post Grenfell, all public sector bodies need to have a good understanding of the maintenance needs and the health and safety issues around their properties.

The failure to maintain can have far more significant costs than just those of repairs.