08 May 2008

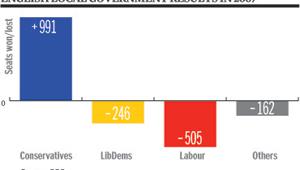

One certain result of Labour's rout in the May 1 elections is that it will become a tax-cutting party – or, at least, seek to portray itself as one ahead of a likely 2010 general election.

All three main parties face the same dilemma: how to offer lower taxes for the average voter, while not reducing receipts from taxation too much. They face two conflicting pressures: first, the increased evidence that voters are hostile to further rises in taxation; second, the absence of any fiscal room for manoeuvre in view of the deteriorating borrowing position.

Moreover, it is no longer possible just to shift taxes from individuals to companies since businesses can – and do – shift their head offices in order to minimise their tax liabilities.

The past six months have illustrated all these constraints. The potency of the tax issue was shown in the autumn when shadow chancellor George Osborne not only ignited his party conference but also won widespread public support by promising to increase the threshold for inheritance tax to £1m. The 'million-pound moment' forced the government to respond and changed political perceptions about tax.

There is also ample evidence that traditional Labour supporters were reluctant to turn out to vote for their party last week because of the row over the abolition of the 10p starting rate of income tax.

We have seen long-term cycles of support for – or at least acquiesence in – higher taxes. But then, after a period when both taxes and public spending have risen, concern increases that the money is not being well spent and tax resistance becomes a major political factor.

Complaints by skilled manual workers about increased deductions from their pay packets played a big part in the Labour defeat of 1979. The Conservatives portrayed themselves as the tax-cutting party, even though it was a long time before they were able to reduce the tax burden, as opposed to shifting the balance from direct to indirect taxes.

During the 1990s, concerns developed about inadequacies in public services, notably schools and the NHS. But Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were very cautious. Before Labour's election in 1997, they promised not to raise the basic or higher rates of income tax, or to broaden the VAT base. Instead, we got stealth taxes.

It took until 2002 for Brown to announce a rise in direct taxes, via an across-the-board increase in employer and employee national insurance contributions – and that was specifically linked to spending on the NHS. This move was broadly accepted.

However, that phase is now clearly over, and more recent polling evidence shows that voters are not only very sceptical about whether the big rises in public spending in this decade have been well spent but are also strongly opposed to further rises in taxation.

A YouGov poll for the Sunday Times in March this year showed that two-thirds of the public believe that the overall amount raised in taxation is too high and that the government should tax and spend less. A fifth think the overall level is about right. Labour voters are evenly split between the two options.

Three-fifths of voters, according to the same poll, think taxes can be cut without public services suffering because it is possible to run services more efficiently. Just under a third believe that tax cuts – leading to less money being spent on public services – would mean that they would suffer. Labour voters split, 53% to 42%, in favour of the latter view.

This voter resistance has been reflected in the uproar over the abolition of the 10p tax rate, and a sense that ordinary people are already paying enough in taxes. And, as in the late 1970s, the protests have come at a time when the government has little or no fiscal flexibility. It is very hard for Chancellor Alistair Darling to find a straightforward solution to the 10p problem because any obvious response, such as raising the starting allowance or threshold, could be very expensive.

So the government, in common with the opposition parties, is trying to help the worst-off without further increases in the overall tax burden. Even the Liberal Democrats, who previously backed some increases in taxes, now say their objective is to reduce taxes overall if possible.

The government's broad approach of limiting the real growth in spending to no more than 2% a year for the foreseeable future is intended to free resources both to reduce borrowing and, in time, to allow some reduction in the tax burden. This approach is broadly accepted by both the main opposition parties, despite differences of emphasis.

Commentators such as the Institute for Fiscal Studies think-tank believe taxes need to be raised, as soon as practicable, and possibly by as much as £8bn, in order to get public finances back on a healthy path.

So, as all parties accept, the most that can happen is a shift of the tax burden. The LibDems have so far been the most explicit, proposing a big increase in various green taxes in order to finance cuts in direct taxation – though there is the complication that they want to replace council tax with a local income tax.

The Conservatives have been cautious so far, apart from their pledges on inheritance tax, capital gains tax and taxing non-domiciles. There has been talk of removing the 'marriage penalty' from the tax system, but otherwise Osborne has largely promised in general terms that any new green taxes would go into what he calls a 'family fund' to reduce direct taxes.

A further constraint is the global business environment, which gives companies more opportunity to cut their tax bills by shifting their operations around the world. Thanks to Brown, Britain already has the lowest corporate tax rate among the Group of Seven industrialised countries, but faces growing competition from Ireland and Switzerland, which are seeking to attract businesses. A number of leading groups have said they are considering shifting their tax bases to Ireland.

These pressures were seen in the business reaction to the government's proposals on capital gains tax and non-domiciles, which led to modifications.

Business has also campaigned for reductions in company taxes. In practice, there is little scope for the government to raise more money from the corporate sector. The Conservatives have pledged to cut the small companies' tax rate from 22p to 20p in the pound, financing this by scrapping the annual investment allowance.

They would also cut the corporation tax rate (already reduced by the government) and finance that by removing some reliefs and reducing capital allowances. In addition, the Tories are proposing changes in the taxation of foreign profits to discourage companies from relocating their head offices away from Britain.

In response, the government has set up a task force aimed at keeping Britain's tax environment competitive, while Brown has hinted at cuts in corporation tax 'when we can afford to do so'.

The politics of taxation have changed to leave governments – and opposition parties – with little scope for dramatic initiatives. Watch for the smoke and mirrors.

Peter Riddell is chief political commentator of The Times

PFmay2008