Quick wins

Topping $1k on health: Global health spending per head works out at just over $1,000 a year, according to World Bank data, a significant hike on the $462 recorded in 1995. Per capita spending is highest in Switzerland at $9,674 and lowest in Madagascar at just $14.

Less like a chimney: Just 26% of Americans now smoke a pack of cigarettes a day, the lowest level recorded by Gallup, which has been tracking US smoking habits for seven decades. The equivalent figure in the mid-1940s was 55%.

Weight of the world: If all adults had the average Japanese body mass index of 22.9, total biomass would fall by 14.6 million tonnes – the weight of 235 million people, according to research published by BMC Public Health.

Chinese medicine

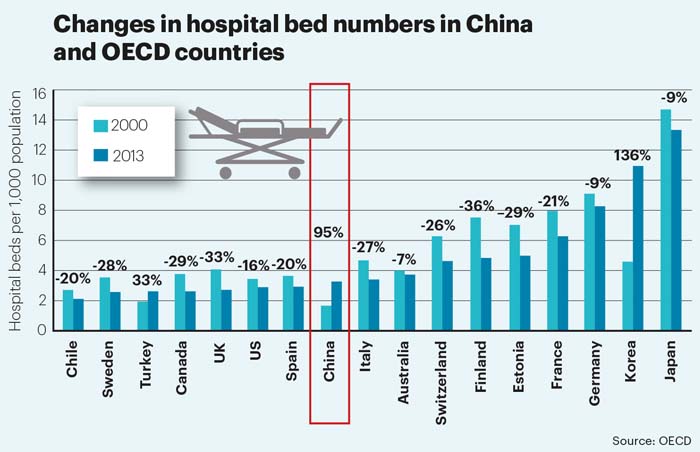

China’s health system is over-reliant on hospital care. A World Bank report, produced with the Chinese government and the World Health Organization, notes that China has more hospital beds per 1,000 population than the US, UK and Canada. Hospital bed numbers doubled between 1980 and 2000 and doubled again between 2000 and 2013.

The World Bank says this is contrary to the pattern observed in most other countries where there has been a move away from hospitals to primary care, and a consequent decline in the number of hospital beds. As the graph shows, Korea is another notable exception to this pattern, seeing a huge 136% increase in beds.

China is being encouraged to adopt a health system centred on primary care and focused on health outcomes, which will offer better value for money.

Lottery of life

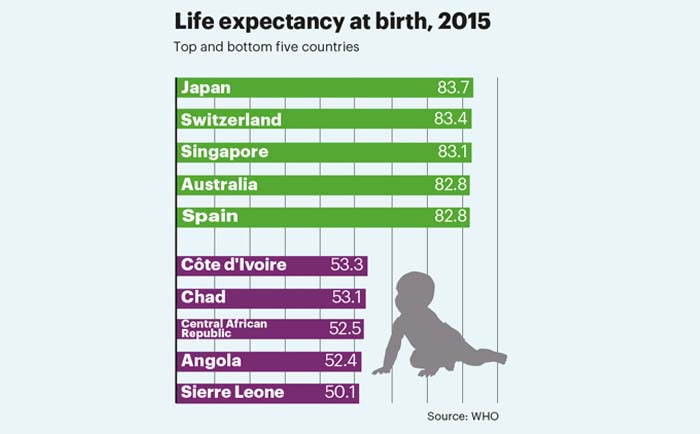

Despite some impressive recent gains in global life expectancy – it improved by five years between 2000 and 2015 – World Health Organization data shows up some stark inequalities.

While the average Japanese, Australian or Swiss person can expect to live into their early 80s, in the poorest parts of Africa, life expectancy is much lower. In Sierra Leone, for example, an average woman only just lives past her 50th birthday, while a man can expect to die at 49.3. Babies born in 2015 can expect to live for 71.4 years on average, but individual outlook will depend on where in the world they are.

Spending recovers

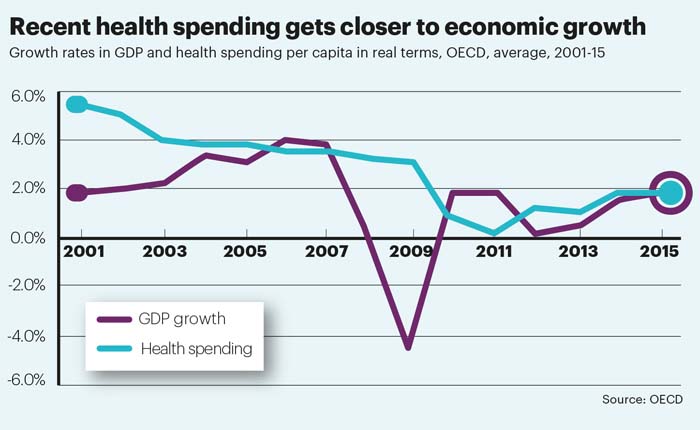

Health spending in the wealthy countries of the OECD has been rising slowly after a period of steady decline. The graph shows that spending fell sharply between 2009 and 2011, mirroring the dramatic plunge in GDP growth that followed the 2007 financial crisis.

Increases in government and compulsory insurance spending are driving the renewed growth, the OECD observes, but it adds that questions remain over whether current financial resources for healthcare are adequate or being used in the most effective way.

Clinical staff for the better off

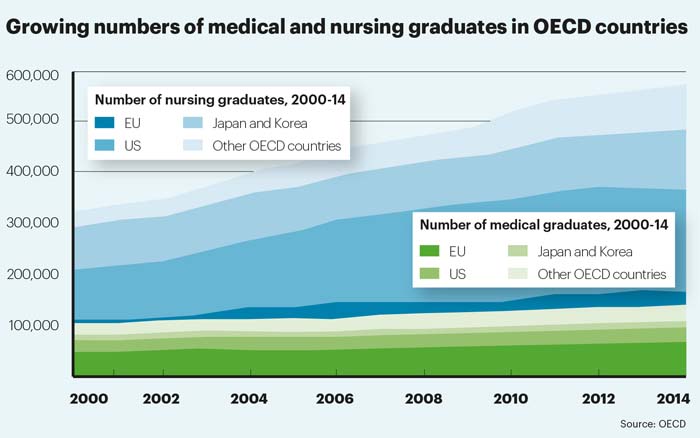

The affluent world has seen a significant rise in doctor and nurse numbers since the turn of the millennium. According to OECD data, the number of medical graduates across the group’s 35 countries rose by 32% between 2000 and 2014, while the number of nurses went up by a staggering 76%. The increase in nurses was particularly marked in the US, where numbers doubled over the period. The 22 EU countries in the OECD also saw strong growth, with medical graduates rising by 37% and nursing graduates by 48%.

The reason behind the growth was concern about the imminent retirement of baby boomers, which prompted OECD governments to invest in training programmes. Immigration of foreign-trained doctors and nurses have also helped keep numbers buoyant.

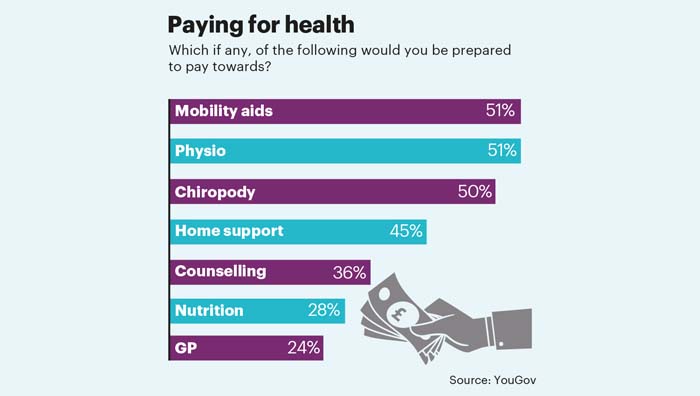

Can pay, would pay

One in four Britons would pay to see their GP, research carried out last year by pollsters YouGov found. However, there was much more enthusiasm for payment for ancillary services.

Half of respondents said they would be willing to pay for mobility aids, physiotherapy or chiropody, and just over one third said they would be prepared to pay for counselling and talking therapies.

More than half of respondents (56%) revealed a pragmatic side, saying they recognised that the NHS cannot do everything.

Fat is a fiscal issue

Taxes on sugar and fat are back on the menu after Food Standards Scotland floated the idea of a levy on junk food. In a paper published in August, the Scottish Government agency said legislative and fiscal measures should be considered to help improve Scotland’s notoriously bad diet.

Mexico is one of the world’s trailblazers in this area. In 2014, it brought in a tax of one peso per litre of sweetened beverage in an attempt to lower obesity and diabetes levels. An evaluation of Mexico’s tax published in the British Medical Journal in November found that sales of sugary drinks had declined by 6% a year after the tax took effect, with the greatest reduction among the poorest households.

France has introduced a sugar tax similar to Mexico’s, as has the city of Berkeley in California. The measure is also set to be introduced in the UK in 2018.