By David Walker | 4 March 2014

The chancellor will use the Budget to reinforce the prime minister’s recovery message to the World Economic Forum at Davos. But rising house prices and consumption threaten to suck in imports, while the UK’s export markets are running into trouble

We know where Chancellor George Osborne won’t be buying hamburgers as he burns the midnight oil preparing his 2014 Budget – after the fuss following last year’s spending review, the spinmeisters won’t let his staff anywhere near upmarket Byron’s.

But there are no prizes for guessing what’s top of the No 11 iPod playlist. Happy days are here again, the American post-crash hit, is tune of the season in Downing Street. Cue some neat political shape-shifting. The Tories are borrowing a song from the era of Democrat FDR while Ed Miliband is channelling the other Roosevelt, Teddy. Though a Republican, he hammered the cartels and took the little guy’s part against the corporations (his latest biography is said to be bedside reading for the Labour leader).

Not that it will provide much solace in the face of the figures in Osborne’s red box. The numbers do indeed stand up the coalition’s riff on UK recovery. Unemployment continues to fall – February even saw a spate of stories about employers having to push up pay rates to keep and attract staff; the British car industry reports surging sales;

consumer confidence is high.

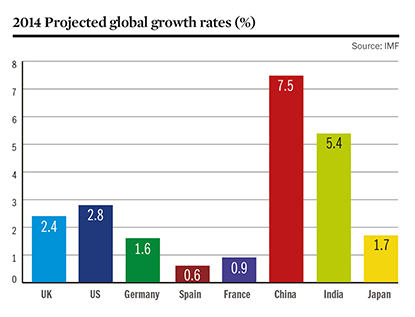

Measured against the eurozone’s anaemic 1% projected growth this year, the UK’s 2.4% looks rather impressive. According to the latest IMF World Outlook, it’s barely less than the US (2.8%) and far better than Germany (1.6%), Japan (1.7%) or France (0.9%). Compared to most other advanced economies, we’re walking tall.

As for looking the rest of the world right in the eye, that story is going to be harder to stand up. Just as the south and west coasts of England have been battered by gales that got going somewhere in the Pacific, so globalisation’s post-2008 downside has been demonstrated by currency mayhem and deep angst over emerging markets. How many City wiseacres are currently cracking the one about emerging markets being markets you need to exit in an emergency?

Chancellors – and this was as true of Osborne’s predecessors – tend to cite international economic conditions when they need a scapegoat, not to explain why a national economy is doing well. The Treasury knows UK growth can’t rely on rising house prices and consumption, which bring more imports. But exports depend on resilient demand in countries with appreciating currencies; the collapse of the Turkish lira and the Indonesian rupiah, not to mention the Brazilian real, doesn’t seem to bear that scenario out.

Brazil and Indonesia, of course, barely count as UK trading partners, compared to the rest of Europe. The trouble is, you can’t walk tall if you are constantly stooping to slag off your nearest and dearest, particularly the eurozone where, though the eurosceptics don’t like it, the UK does more than half its import and export trade.

France, for example, took 7.5% of UK exports in 2013, twice the proportion going to China. So why did the Conservative party chair, Grant Shapps, attack the government of François Hollande a few days before the Anglo-French summit, accusing it of taking France ‘back into the dust’? In place of this cross-Channel sniping, a more honest response might have been to acknowledge that the UK, like France, lacks any kind of big idea for how an open, advanced economy dependent on a few vulnerable sectors for exports is to thrive as the world gropes its way forward, still dizzy from the effects of the 2008 crash.

The uneven nature of the way ahead is illustrated by the IMF’s projections, which expect the world economy as a whole to grow by 3.7% in 2014, with emerging and developing economies forecast to grow on average by 5.1%. The latter percentage, in theory, could sound like the great opportunity extolled by David Cameron on last year’s visit to the east. But take China (projected growth 7.5%) out of the graphs and the picture takes on many more tints of grey.

In Latin America recently, old habits have returned. Argentina and Venezuela contrive to turn themselves into basket cases once again; who would bet on Mexico when the state is collapsing (and the currency imploding)? In Turkey, deep political and religious strife that is hard for even the most seasoned observers to fathom coincides with capital flight, provoking the central bank into a drastic interest rate hike. The central bank governor is immediately condemned by the prime minister. Perhaps the UK shouldn’t rely on Turkey as a trade partner.

Unless, that is, you are one of those bestselling economic gurus such as Jim O’Neill, the former chair of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, or Michael Spence, the 2001 Nobel laureate, who see what’s happening this spring as mere blips on an upwards path towards general prosperity. In his book The next convergence, Spence predicts that 75% of the world’s people by 2050 will live in countries classed as ‘advanced’ in terms of GDP per head.

In the meantime, the Brics group of emerging economies identified by O’Neill no longer includes South Africa; Russia, increasingly authoritarian, its economy regressing into dependence on minerals and hydrocarbons, is also out. Brazil faces the drop, especially if this year’s World Cup is badly organised. As for the latest coinage by O’Neill: take out Mexico, Turkey and Indonesia – all in the midst of crisis – and what is left of his Mints is Nigeria, another oil-dependent economy that has already been wracked by secession and domestic instability.

And don’t forget political risk, hard to price, but omnipresent. China and Japan could not possibly go to war over islands in the East China Sea, could they, with the ¥124 trillion in the Japan Government Pension Investment Fund needing to find a home somewhere, let alone the growing value of Chinese ownership of US assets? But that’s analogous to what they were saying in 1914 in Europe.

The world economy is vastly more interlinked now, but that fact tells you very little about international cooperation. Hot money disappears from Istanbul partly because of jitters over the reduction of ‘monetary easing’ by the US Federal Reserve. Putting a sensible grey-haired woman in charge (Janet Yellen was sworn in as head of the Fed last month) won’t make American policy any less inward focused: the world superpower turns out to feel no responsibility for international monetary ordering.

That’s another sure sign that the international financial regime has still to come to terms with 2008. The G8 grouping of rich countries did great work in 2009 in agreeing to support demand. But that was then. Transatlantic, let alone global, agreement is hard to reach on anything much these days. Trade talks have stalled. The imprint of the G20 is hard to spot. The IMF has yet to agree on rules for sovereign debt.

The Republic of Ireland and Portugal may have escaped their bailouts but political instability stalks Greece and Hungary. No wonder analysts’ bulletins warn that state bankruptcies have not gone away.

Early signs in 2014 have demonstrated another global imbalance. The Chinese authorities want to cool new bank loans, but other countries are complaining that banks won’t lend for productive, employment-generating investments.

Banks will lend for house purchases – and without such loans the chancellor would have a lot less to crow about. But a house price bubble is not going to power UK growth sufficiently to wrest back the massive loss in GDP compared to the pre-crisis trend. Which brings us back to exports as the only real source of sustainable growth.

We’re getting there, says Osborne. In his Budget speech, the chancellor will probably name-check the firms to which he and his Downing Street neighbour have lately been dragging the TV cameras: Nissan and Jaguar Land Rover (the UK now exports more finished cars than it imports); plus Hornby, the model train maker, and fan company Vent-Axia, all examples of the business reversal that Cameron has been extolling in recent speeches. ‘Re-shoring’, the return to the UK of production lines that were abandoned in favour of Made in China, India and elsewhere, is apparently the new game in town.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, the prime minister claimed more than one in 10 small- and medium-sized businesses had in the past year brought ‘some production’ back to the UK. This was ‘more than double the proportion sending production in the opposite direction’. He cited the relocation of a factory from China to Leeds by food manufacturer Symingtons, and some repatriation of jobs by the UK fashion brand Jaeger. ‘

When mobile network company EE recently decided to move 300 call centre jobs from the Philippines to Northern Ireland, they didn’t do it because wages were lower. They did it because productivity was higher and because the company decided it would be more successful by having a more local call centre for its customers,’ the PM claimed.

Yet the UK’s deficit in international trade in goods and services shows all its old stubbornness, even if exports to China increased by 10% in the quarter to November. Imports from China were just under the value of the trade gap in goods, £10bn, in the same period. The UK economy sucks in goods and exports services but to nothing like the same value: within the gap is a mix of repatriated profits and capital flows. That’s why walking tall involves bowing and scraping to overseas investors, and the sale of sensitive energy and telecoms infrastructure to the Chinese.

Walking tall also implies knowing where – and in what direction – you are heading. It surely matters to UK plc that the country’s defence and diplomatic posture has been shrinking.

Is this ‘post-globalisation’, to be replaced by the new mantra of ‘regionalisation’? If so, politically it’s a bit of a problem, especially if it means trying to make the European economy work, as it heads towards deflation and derailing of the fragile EU recovery.

Osborne’s Budget party will probably also be pooped by the business secretary. Vince Cable has already noted that sterling has lost a quarter of its international value since the crash but, instead of cheaper currency boosting overseas sales, UK trade performance has improved only feebly. In the three months to November 2013, he said, UK exports to China came to a third of the value of the total deficit in visible trade over the same period. And he wasn’t finished there.

Eeyore Cable has also been complaining about job creation being concentrated in London and the Southeast – that ‘giant suction machine, draining life out of the rest of the country’. But Westminster doesn’t want to hear about difficult, structural questions, even – or perhaps especially – in a year when Scotland’s departure from the UK could make the imbalance within England look even more dramatic. Nor will Osborne’s audience be offered much that’s difficult to grapple with about the UK’s international imbalances, at a time of deepest uncertainty about the trends unfolding in the world economy.

Ace tactician Osborne will use the Budget to tease and tempt middle-income voters, insisting the statistics prove that for the UK, at least, the glass is half full, and to avert their eyes from what might lie ahead, beyond 2015/16 – such as an import explosion followed by a sterling collapse, followed by an interest rate hike, wreaking havoc with over-borrowed households. All that is for another time, another place.

David Walker is a writer and commentator on public policy and international issues

This feature was first published in the March edition of Public Finance magazine