Trust and confidence by the general public (and society at large) in the charity sector are crucial as a basis for ensuring its health and growth. Scandals, however isolated, have the potential to inflict considerable damage, including undermining the sector’s ability to access funding. Often these arise because the behaviour of particular charities is at odds with the public’s expectations. Examples of this can relate to disquiet over what might be viewed as excessive executive salaries or highly questionable fundraising practices. Moreover, the action (or inaction) of government and/or regulators can contribute to the collapse of publicly funded charities. When trust is eroded, donors withhold funds, volunteers limit their involvement, regulators investigate and regulation can become more intrusive. Often the biggest losers are vulnerable beneficiaries and society at large.

Trust is a belief in the reliability, truth or ability of something or someone. But what does trust look like for those (funders, donors, volunteers, beneficiaries and the general public) who engage with charities? Common expectations are that charities will both ‘do good’ (create positive change) and ‘be good’ (spend wisely; act ethically). While these expectations hold, stakeholders continue to place trust in and support charities; when trust is lost, damage results.

How, then, can trust be (re)built? Different stakeholders develop trust in different ways. Some might require ‘hard evidence’ on which to base trust: such as seeing the ‘good work’ done or being convinced that ‘good work’ has been done. For others, trust can be based on a relationship or identification with a charity: for example, following repeated interactions, recognising shared values or emotional connections. Still others may place trust based on the institutions of the charity sector: such as relevant laws, codes, regulation, registration and reporting requirements. In many cases, these aspects impact in an interrelated and layered manner to influence stakeholders.

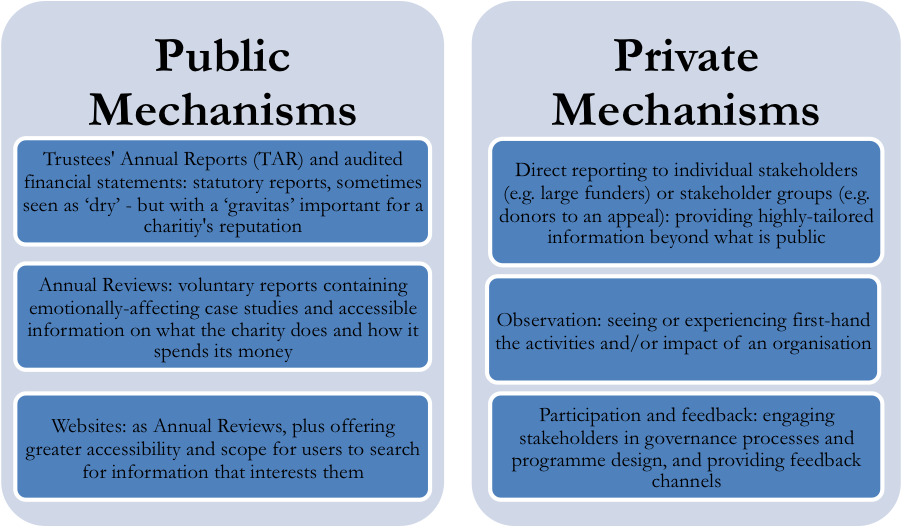

On the basis of ongoing research, we argue that, particularly in the case of large charities (which are often at a distance from many of their key stakeholders), there is a need to use a mix of ‘public’ (available to all) and ‘private’ (tailored to particular stakeholders) accountability mechanisms to engage with stakeholders. This ‘toolbox’ of mechanisms operates interconnectedly, and, if used sensitively and strategically, can significantly enhance accountability and support the (re)building of trust. Examples of the mechanisms are:

Charities can tailor their use of this ‘toolbox’ to meet the expectations of their various stakeholders: often using multiple accountability mechanisms with the same stakeholder, and specific mechanisms with multiple stakeholders. For example:

- Large funders often expect to receive good-quality TARs and financial statements, but then anticipate/demand more detailed information through direct reporting (they ‘trust but verify’). Over time, this allows two-way conversations, improved transparency and meaningful funder/charity relationships to develop, thereby enhancing trust, and consequently reducing the need for costly direct reporting.

- For individual donors, accessible communications such as Annual Reviews, websites and specific donor reporting (to give a broad sense of what the charity does and how it spends its money) can help propagate an emotional connection and identification-based trust.

- With beneficiaries (who often fail to engage with formal public mechanisms), observation, participation and feedback may be particularly important in trust-building.

- Trust (and engagement) from the general public (a group often remote from core charity activities) can be encouraged by good-quality, publicly-available communications, awareness of appropriate charity regulation and opportunities to observe what goes on.

Private and public mechanisms reinforce each other. In our research we argue that public mechanisms are crucial in meeting baseline stakeholder expectations, but are inadequate in building a substantial trust relationship. To do this, private mechanisms need to be mobilised; but this is not easy. Identifying stakeholder interests and needs, establishing an appropriate mix of mechanisms, considering the cost and efficacy of specific private mechanisms and the difficulty of reaching/engaging some important stakeholder groups all provide challenges.

A number of implications arise from our research:

- If charities (and the charity sector) are serious about (re)building trust they need to: consider how they can best implement and use private mechanisms of accountability with stakeholder groups who, at times, are hard to engage; and experiment creatively to achieve an appropriate mix of private and public accountability mechanisms.

- Those who fund charities: should reflect on what drives their trust (or distrust); and consider what is needed to cement a substantial trust relationship (possibly a more-focussed direct reporting, ongoing transparent conversations, or greater engagement via observation?)

- Regulators and sector bodies need to: recognise the potential for private accountability mechanisms to create and underpin trust relationships; and, in whatever ways possible, encourage the development and utilisation of such means.

This article is based on an ongoing programme of research into charity accountability, aspects of which were presented by the authors at the Public Services and Charities: Accounting, Accountability and Governance at a Time of Change conference held at the Centre for Not-for-profit and Public-sector Research, Queen’s University Belfast in 2017 and subsequently published in the British Accounting Review (available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.09.004 (paywall)).