Since the general election, there has been a chorus of calls for the cap on public sector pay to be lifted, including voices from within the Cabinet. But so far, the Chancellor has been singing from a different hymn sheet. It’s not hard to see why – the NHS pay bill is more than £50bn each year (by far the largest item in the Department of Health’s £117bn revenue budget), and holding down the pay of public sector staff is one of the few levers a government can pull to control public sector finances.

However, once that lever has been pulled, you would hope it wouldn’t stay locked in position for nearly a decade. Yet that is exactly what has happened since Alistair Darling – the then chancellor – first introduced the pay cap in 2009. There is now growing recognition that the NHS Pay Review Body is right when it says ‘we are approaching the point when current public sector pay policy is no longer sustainable for the NHS’.

Since the recession, pay awards for the public sector have either been frozen (in 2011/12 and 2012/13) or capped at 1 % (2013/14 onwards) for all but the lowest-paid workers. This arrangement is not due to end until 2020/21. As a result, the value of NHS staff pay has decreased significantly as the cost of living has increased.

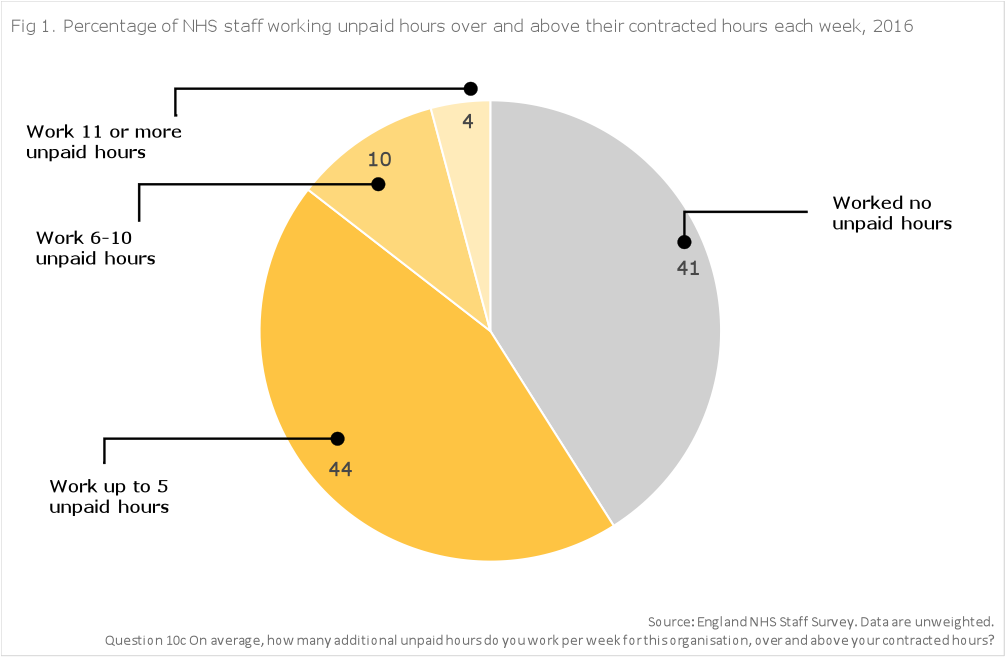

For example, Band 5 level nurses, who might be responsible for wound care or administering medications to patients, have seen the value of their pay fall by 7 % between April 2010 and April 2016 compared to inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index, and by 11 % against the Retail Price Index. The chancellor has recently said that public sector pay policy must be ‘fair to public-sector workers but also fair to taxpayers’. The number of unpaid hours NHS staff work outside their contracts (Figure 1), despite years of this declining value in their take home pay, may suggest the taxpayer is getting a good enough deal already and that we are at risk of further eroding our social compact with NHS staff.

So as the government decides whether it wants a hard or soft version of austerity, it will be faced with some difficult choices on public sector pay. Does it try to hold the line on pay restraint until 2020/21? Does it target pay awards at certain professions – such as frontline nursing, police, teachers – or the whole public sector? Does it increase public sector spending sufficiently to increase both the pay and number of staff, or does it explicitly trade these factors off and tell the electorate that it could have had more nurses but the government has chosen to opt for fewer, fairer-paid nurses instead?

The view from the NHS on these options is clear – as Jim Mackey, chief executive of NHS Improvement, has noted, easing or ending pay restraint for NHS staff must be supported by additional funding from central government rather than being drawn from the existing NHS funding settlement. Unfunded pay awards for staff could be a toxic mix for the NHS, if employers then have to reduce the number of staff they can afford to employ. This will be unpalatable for a Treasury that is facing unexpected spending pressures from new infrastructure projects in Northern Ireland, longer-term economic uncertainty from Brexit, and shrinking fiscal headroom as reform of the triple lock and winter fuel payments grows less politically feasible. But significant amounts of capital and transformation funding within the NHS have already been diverted to support the day-to-day running costs of services, and there is even less room for manoeuvre left within the NHS financial settlement.

But there is an even more fundamental question of what the government would be purchasing if it decided to end pay restraint in the NHS. In addition to pay packets that have fallen behind inflation, the workforce pressures in the NHS include significant staff shortages, high vacancy rates and challenges to morale.

There is an argument that removing pay restraint in the NHS will boost recruitment and retention of staff. With the end of student bursaries for nurses and allied staff, the NHS will now have to compete with other fee-paying courses for potential students – public sector pay caps are not a great selling point in this market. If trained nurses in other settings, including the private sector, are responsive to pay levels then an end to pay restraint may see workers move back to the NHS.

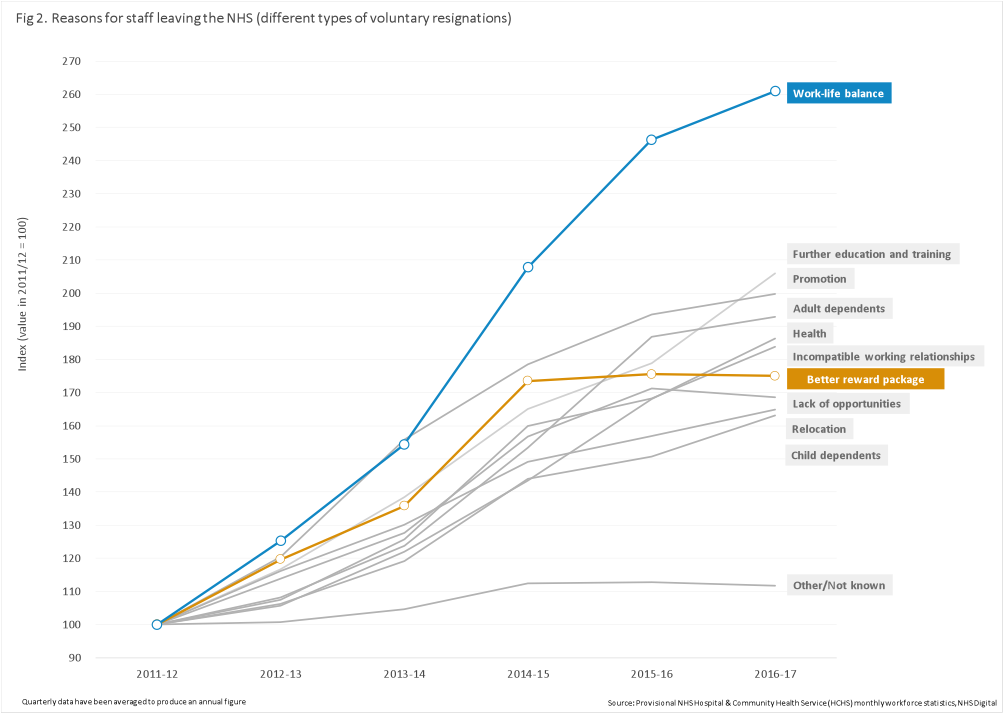

But even bearing this in mind, the Pay Review Body was unconvinced that pay rises in line with inflation would encourage more staff to join the NHS or persuade fewer staff to leave. Data from NHS Digital (Figure 2) also suggests that the fastest growing reason for staff voluntarily resigning from the NHS is work–life balance, and not the reward package on offer (or even the euphemistically categorised ‘incompatible working relationships’).

I once had a boss who would ask the same question every time a discussion on a policy issue was heading off-track: what is the problem you are trying to address? Ending public sector pay restraint would help address the falling value of staff salaries but would not be a panacea for the workforce challenges of the NHS. The problems are wider than pay and the solutions offered by employers to support better work–life balance and morale should be wider as well – as others have pointed out. None of this is an argument to resist change to NHS pay policy – the Pay Review Body report makes clear this is untenable. But let the ‘buyer’ beware, or at least be aware, on what extra spending on NHS staff pay can achieve.