In a speech last month, business secretary Greg Clark reaffirmed the government’s commitment that its industrial strategy would ‘create good jobs for all people in all parts of the country’. The fact that the speech was delivered in the West Midlands, with its new mayor Andy Street outlining what it would mean for the region, demonstrated that city regions will be at the heart of designing and delivering their own industrial strategies.

Pursuing an industrial strategy signals the state taking an active role not just in improving individuals’ abilities to access the labour market – through boosting skills or transport links – but also in how well local economies provide jobs.

A new JRF report shows just why an economic strategy that creates more and better jobs across the UK’s cities is so needed. The national picture on jobs is good; a higher proportion of the working age population are in work than ever before. But a deeper dive into people’s experiences of the labour market shows many issues that need addressing.

Being unemployed is just one way people can fall short of having a good job. One in eight of the labour force in the 12 cities looked at in the report is underemployed – they are in work but not working as many hours as they’d like. Many other potential workers are not actively searching for work despite the fact they do want to work for a variety of reasons including not being able to find suitable work due to disability or caring responsibilities. In all, just under a quarter of the workforce in the UK’s major cities are unemployed, underemployed or unwantedly inactive.

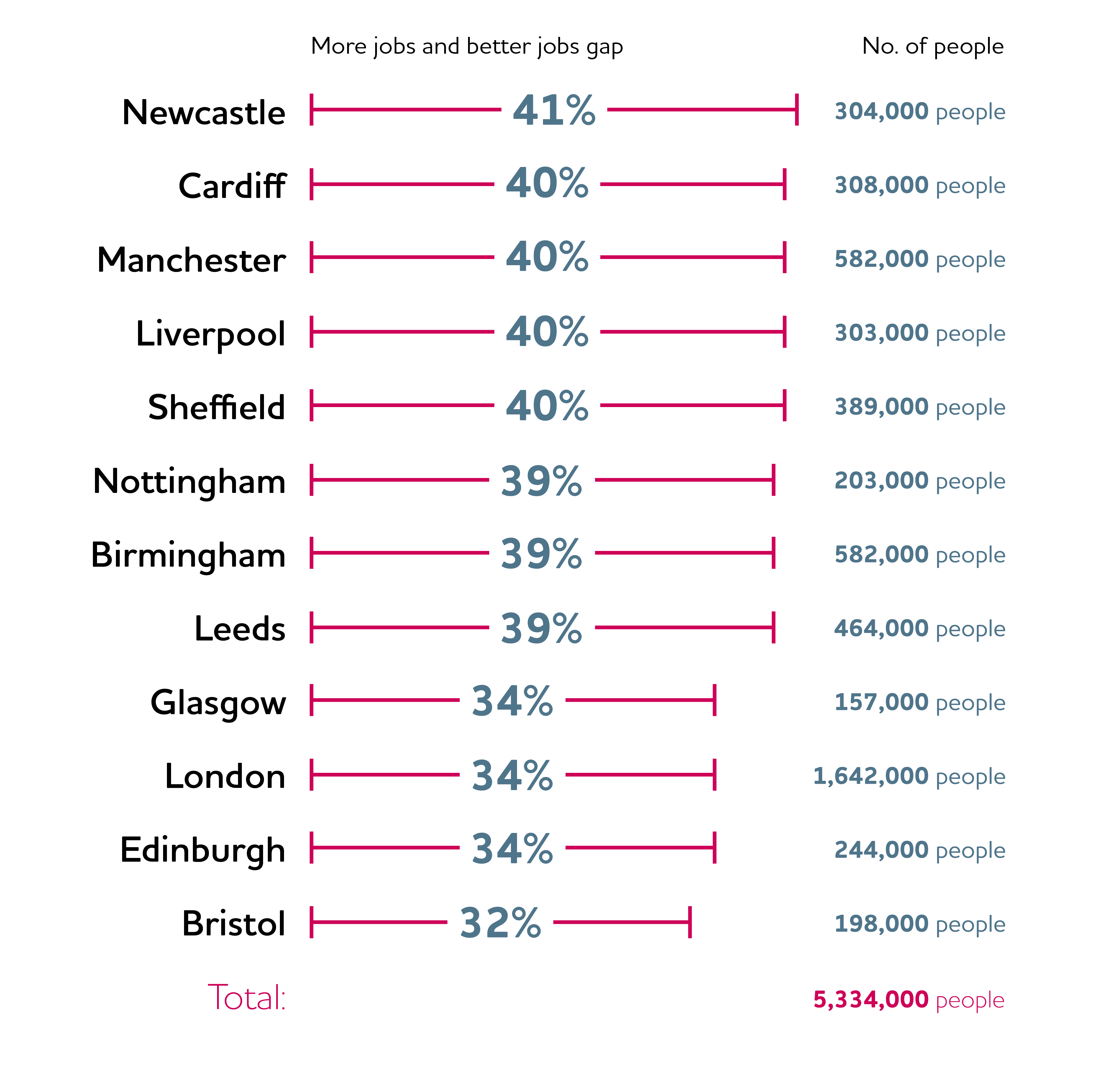

Next is the issue of job quality, including pay and security. One in six of the labour force is paid less than the Living Wage (or in London the London Living Wage) – the amount a representative household needs to earn to achieve life’s necessities. In total, we estimate the More and Better Jobs Gap in the UK’s major cities – the number of people in the workforce who don’t have a good quality job – at 5.3 million people, equivalent to the combined working age population of the West Midlands, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region and Tees Valley.

The analysis also pinpoints specific issues for different cities. In the West Midlands just two-thirds of the working age population is in employment, compared to three quarters nationally, and the unemployment rate stands at 9%. In Manchester, just under a fifth of the workforce earn less than the Living Wage. The map below shows the scale of the More and Better Jobs Gaps in UK’s major cities. The government is right we’ll need different locally led industrial strategies in different cities.

We will learn much more about how the industrial strategy will play out as the government publishes its white paper in the autumn and the new mayors lay out their plans. One thing they need to watch out for is policy priorities being drawn towards the ‘shiny and new’ – hi-tech ‘world-beating’ industries. Greg Clark used his speech in Birmingham to launch the Faraday Challenge, a competition to boost research and development of expertise in battery technology. Andy Street has talked about the West Midlands’ potential in Smart Energy and robotics.

But investing in the shiny and new is unlikely to be enough to deliver the more and better jobs we need. These industries create a relatively small number of jobs, so we’re relying on the benefits spilling over to the rest of the population. Recent research from the Resolution Foundation found that high-wage jobs do create more jobs in the local economy, but the jobs that are created are low quality ones. They might do a bit to close the More Jobs Gap, but only by swelling the Better Jobs gap.

What would a better approach look like? JRF research looked at innovative practice from cities around the world where local leaders have prioritised creating more and better jobs. Here are three lessons from abroad that city leaders here should take note of.

Target sectors that deliver growth in good quality jobs. Local leaders in San Antonio, Texas, have identified priority sectors based on the types of job they create as well as the local economy’s existing assets. By targeting sectors delivering middle- rather than high-skilled jobs, they identified health services, business systems, IT and vehicle maintenance and repair as their priority sectors – a very different set to those often pursued through industrial strategies. UK cities could estimate the number and types of job provided by different sectors that align with their current assets, and prioritise the ones that best directly deliver good jobs.

Pursue demand-led skills strategies. The Chicago Manufacturing Renaissance Council attempts to overcome the low-skills trap that exists in the disadvantaged West Side of Chicago by boosting both the supply and demand for skills. The council brings together manufacturing employers and education and skills providers to design skills programmes that are led by the demands of employers. UK cities could form similar partnerships between employers and training providers to pursue demand-led skills strategies.

Coordination and partnerships to make sure local people benefit. The Limerick for IT scheme formed a partnership of major inward investors, local universities and local and national governments, to work to identify infrastructure and skills needs and then to provide services and skills to ensure people living locally benefited from inward investment. Partnership working between governments, businesses and anchor institutions will be essential to delivering an industrial strategy that creates more and better jobs.

Learning from the examples above would be a start, but wouldn’t be enough to close the More and Better Jobs Gap. Workers in retail, hospitality and care are the least likely to be in a good job, and these sectors aren’t going away. Cities will also need strategies to drive up productivity and pay in these low-paid sectors. JRF will publishing work on how to do this later in the year.

In committing to creating good jobs for all in all parts of the country, the government has set the right challenge for its Industrial Strategy. The government and local leaders now need to find the right policies. Doing so requires making sure sector and productivity strategies create good quality jobs, everyone has the skills they need to participate, and all places have the capacity to create the conditions for more and better jobs.