Consider for a moment what would happen if we voted to leave the EU on 23 June.

The Conservatives would be badly bruised but look to unite to fight Labour rather than fall into disunity. They would also want to agree a quick exit agreement to ensure political, electoral and economic stability. And they would be conscious that they would have to get any deal past a heavily remain-centric House of Commons.

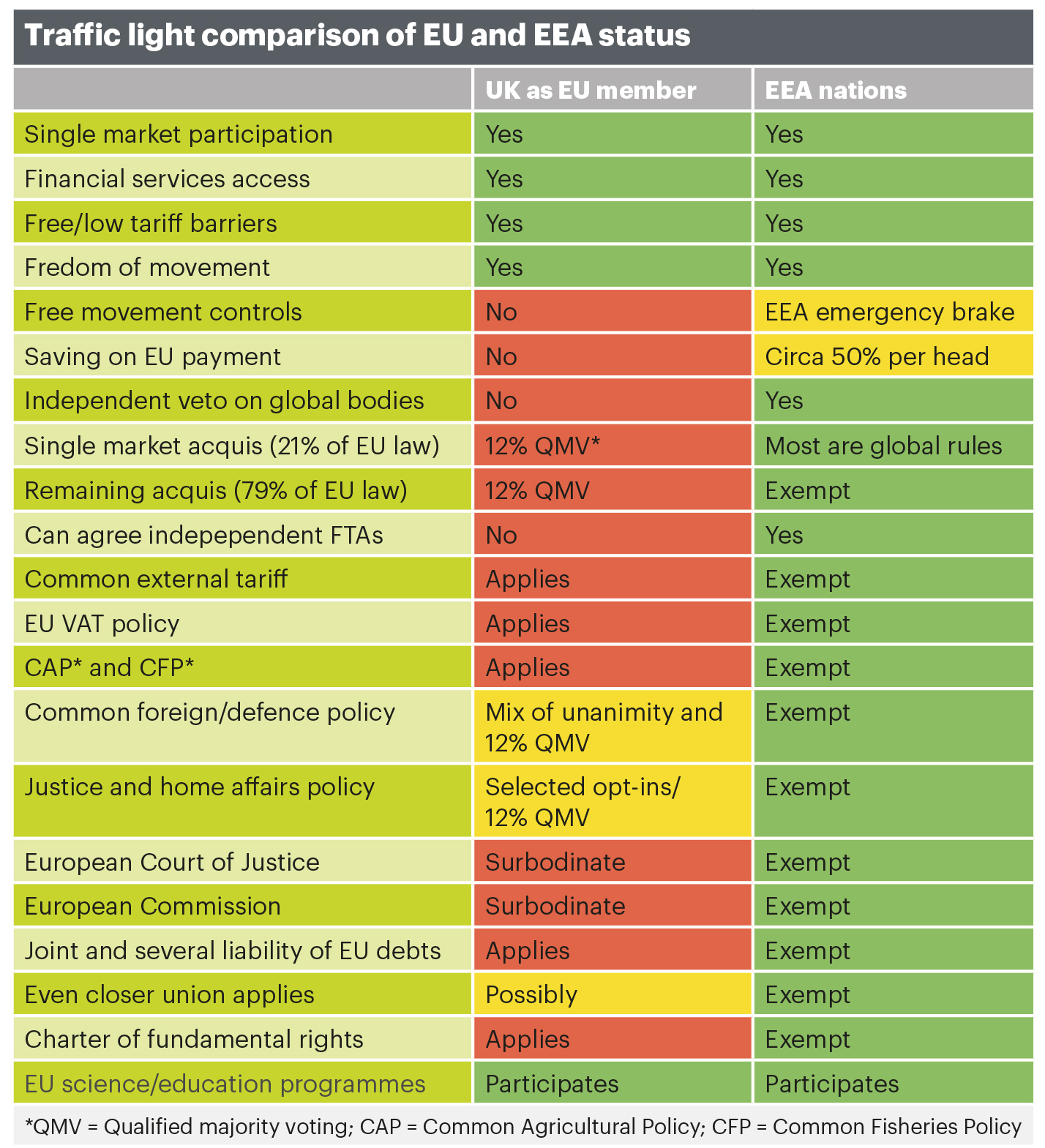

That all points to an exit deal outside the EU but inside the European Economic Area (EEA) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). In other words, a single market-only relationship. Most remain scare stories rest on Britain leaving the single market – fears that are instantly neutralised by an EEA deal. Questions about Northern Ireland, expats, Gibraltar and perhaps even Scotland would also dissipate.

An exit would, however, have a knock-on effect on the EU, perhaps prompting other member states to consider following Britain in leaving. This could set off a dynamic that turns the single market into a genuine Europe-wide market decoupled from the EU; all of Europe could be a part of this on reasonable terms, including better democratic checks on free movement.

So what is the EEA option?

This is the position adopted by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. These EEA countries have a market-based relationship with the EU by having full single market access but are spared the EU’s ambitions for political union.

Liechtenstein: like other EEA countries, Liechtenstein has a market-based relationship with the EU without its legislative controls. Photo: iStock

The option would be very attractive to Britain.

There are, however, several alleged drawbacks to the EEA option that need addressing one by one.

EEA countries have ‘no say’ over EU laws

This is incorrect. EEA countries have a say through structures that allow formal consultation and participation between the EU and EFTA/EEA, particularly in the crucial early stages.

Furthermore, EEA countries exert independent influence in global bodies where the majority of single market legislation now originates. The UK cannot do this because of its EU membership.

Even inside the EU, Britain’s influence is severely constrained. The recent failed EU renegotiation starkly showed its limits.

Finally, as a safety valve, EEA countries have a right to challenge and opt out of new EU laws – a right the UK as an EU member does not have.

EEA countries adopt 75% of EU laws

This is wrong because it takes no account of numerous EU regulations. The real figure is between 10% and 28%, depending on the calculation method. This figure is made up of single market law, the majority of which originates at the global level, where EEA countries exert their influence. Britain adopts 100% of EU law and, at a global level, is increasingly bound by the EU’s position.

EEA countries still have to pay the EU

EEA/EFTA members do pay a small amount for single market access, but not at the levels publicised by the remain lobby who focus on Norway and include ‘Norway grants’, which aren’t paid to the EU but to individual European countries. When that distortion is removed, Norway pays significantly less than the UK.

Free movement will not change

This is very nearly true but for the fact that EEA countries have a permanent ‘emergency brake’ on the four freedoms, including free movement. They have the unilateral power to use this brake and have done so in the past.

Again, EEA countries are in a stronger position while the UK has little influence within the EU. Prime minister David Cameron’s attempt at getting a very limited emergency brake on benefit payments resulted in a messy compromise.

Other objections to the EEA option come from those who prefer a bespoke ‘better deal’. That is understandable. The problem is that it could take 10 years to negotiate – a timescale there will be no appetite for. Plus, Britain’s required relationship with the EU far exceeds a mere trade deal. It is deep and extraordinarily complex, with massive areas of cooperation and joint action, some of which we may want to continue after we leave. Trade is barely the half of it.

The step back to the EEA thus allows a smooth exit without having to deal with everything upfront. It starts an evolutionary journey towards an optimistic global Britain while maintaining open trade with our nearest neighbours and friends.

Such an exit would keep the good things from the EU – genuine cooperation and free movement, which are a positive and necessary part of the deal that would allow trade with the EU to continue uninterrupted.

But, after an exit and over time, the UK – and indeed all of Europe – would shift to an amended settlement. This would be a liberal one where democracy is nurtured, not neutered, and where Europe’s diversity is genuinely celebrated and not constantly shoehorned into a political one size fits none structure from a bygone age. It will focus much more on a single open trading area, not on a country called Europe, with a single government.

The EEA option provides the first step.