A welcome feature of local government secretary Greg Clark’s early months in office were his obvious efforts to be less interventionist and provocatively critical of local government than his predecessor, Eric Pickles. It’s not taken long, though, for it to become clear that he’s not that cuddly, and that the ghost of Pickles Past still haunts the DCLG’s Marsham Street corridors.

In early October in a party conference-pandering move straight from the Pickles playbook, Clark enthusiastically endorsed the government’s plan to amend pensions regulations and procurement guidelines – the aim being to ban councils declining on ethical grounds to invest in or trade with companies involved, for instance, in the arms trade, fossil fuels, tobacco products, and Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank.

So, come November’s Spending Review, it was more disappointing than surprising to hear the communities secretary not so much echo as anticipate George Osborne’s injunctions to local authorities to make good their grant losses by drawing on the billions of revenue reserves they’d built up – precisely as Eric Pickles was wont to do each budget-making season.

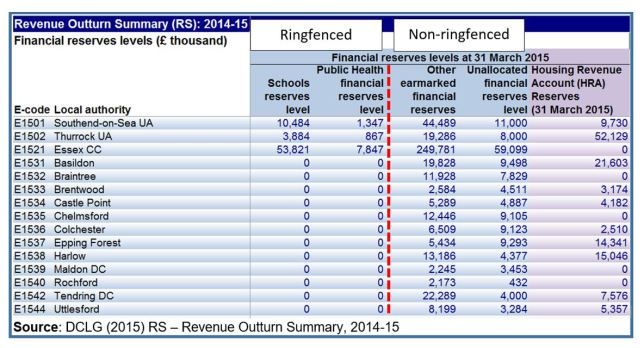

Indeed, the DCLG furnished the chancellor – and, of course, the media – with what he deemed the convincing evidence of councils’ ability to do so, in the form of updated revenue expenditure and financing statistics (pp. 12-13, Table 6). “Today’s figures show how they are well placed to … play their part in dealing with the deficit… with local authorities holding £22.5 billion in non-ringfenced reserves – up 170% in real terms over the last 15 years. Now is the time to make efficient use of their assets and resources to provide the services local people want to see.” (my emphasis).

It was noticeable that Clark used neither of the inflammatory H-words – in contrast to Pickles, who in such situations was unable to stop himself sneering at the ‘hypocrisy’ of councils pleading poverty as they annually ‘hoarded’ their billions of cash reserves. But then he didn’t need to; Pickles’ media-training is by now well embedded, certainly in the tabloids.

Normally, none of this would matter much, apart from irritating any viewers who resent being manipulated into being outraged at some scary big numbers and alleged mismanagement that they have no means of judging for themselves. In this case, though, it came to the attention of Councillor David Finch, Conservative Leader of Essex County Council, who understandably took the whole thing quite personally and proceeded ‘do a Hudspeth’.

You may recall my recent account of the revealing correspondence between David Cameron and Ian Hudspeth, Conservative leader of the PM’s own Oxfordshire County Council, in which the latter patiently and at length put the PM right on a number of misunderstandings he’d revealed about the county’s financial management and indeed about the impact of his own government’s policies. I sub-titled the exchange ‘the gift that keeps on giving’ and, although this wasn’t the form I anticipated a further instalment taking, it certainly fits the bill.

Councillor Finch had been one of numerous council leaders, in addition to the Local Government Association (LGA) itself, who protested back in November that:

“Whitehall should not be dictating how we should be managing our finances and reserves. Holding reserves is simply prudent and effective financial management and is done to ensure that in the event of an emergency or a major incident we can react without impacting other services.”

Politically if not personally, the Essex leader must have had a trying Christmas, not least through local MPs and their constituents having gained the impression that swilling around County Hall was not floodwater, as elsewhere in the country, but oodles of revenue reserves. He therefore wrote Cameron a three-page letter – described on his blog as ‘polite’ and by others as ‘hard-hitting’ and ‘scathing’ – setting out for the PM a few home truths. There were details of the council’s past savings, future enforced cuts, and ongoing budget pressures, but you sensed that, even more than these specifics, what really irked Finch was the flak he’d had to take about the council’s alleged reserves:

“I continue to be alarmed at central government misunderstanding, or even ignorance, about council reserves. Essex MPs have been told by the DCLG that the council is sitting on £300m of unringfenced reserves. We actually only have about £60m. The reality is we have just 23 days of available funding in our general reserve.” (my emphasis)

Like Hudspeth in Oxfordshire, the Essex leader is concerned more broadly about what he terms the “giant disconnect emerging between central government and local government” concerning local financial management (my emphasis). But the reserves issue has specific figures attached – a £240m gap is a big misunderstanding by any standards – which means that the Essex section of the relevant DCLG table enables us to work out what’s probably been going on.

It would seem that the DCLG failed properly to explain, or the MPs failed to grasp, that, near-synonymous though the terms ‘ringfenced’ and ‘earmarked’ may be in any everyday conversation in which they may happen to appear, in local finance lingo they are fundamentally different. The DCLG distinguishes between local authorities’ ringfenced reserves, allocated specifically to schools or public health (though not housing, which is completely separate), and non-ringfenced, which are the rest.

Large local authorities especially, however, earmark often a large proportion of their non-ringfenced (sometimes labelled ‘usable’) reserves for a range of different but particular purposes. Like any prudent budgeter, they set money aside for future spending, rather than having to find it all when it suddenly becomes due by the end of the month. Common earmarked reserves are for financing future capital investment and major repairs, for Private Finance Initiative payments on long-term projects, to cover claims made under a council’s self-insurance arrangements, to enable future savings targets to be delivered, and, not least in recent years, to safeguard against future years’ grant funding reductions.

The non-earmarked remainder – under one-fifth in Essex CC’s case – goes into the council’s General Fund, or Finch’s ‘general reserve’, which will be used to balance the budget if it’s overspent at the end of the year, but, in the meantime and more topically, will be used to pay for sudden and large cost pressures – like damage caused by exceptionally severe weather conditions.

David Cameron, who either doesn’t understand or doesn’t care about these not terribly subtle ringfencing and earmarking distinctions, seems happy to fire off petulant and factually inaccurate letters to his county council leader, and to have his MPs similarly badger their own councils.

Clark’s case, though, is different. He certainly does understand, not least because a CIPFA survey of local authority reserves only last summer spelt out the message in detailed clarity. The numerous “recent changes in local authority funding have significantly increased the level of risk being managed by local authorities”. The radical transformations in service provision on which ministers are so keen have major one-off costs, including redundancy costs that have to be budgeted for. “Using reserves purely to support ongoing expenditure merely postpones the need for cuts and makes those cuts more difficult to deliver when needed…”

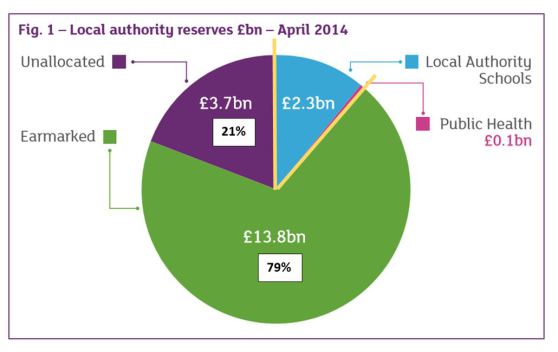

Above all, there were the statistical findings of the CIPFA survey – that, almost precisely reflecting the situation in Essex, nearly four-fifths of councils’ reserves were not being either mindlessly or politically ‘hoarded’, but were already earmarked for specific, and often government-created, purposes. To accuse ministers of ‘going native’ is almost a Yes, Minister cliché and in Clark’s case probably unfair, but he certainly doesn’t seem as cuddly today as he did six months ago.

A version of this article first appeared on the INLOGOV blog