IPPR has published a new report on political inequality and what to do about it. In an ideal world, we would now be setting up a constitutional convention and debating electoral reform, the relationship between the different nations of the UK, and that between the citizen and the state. But the prosaic reality is that sweeping reforms of this kind are no longer on the agenda, at Westminster at least. If a constitutional convention is to take place, it will have to be self-organised in civil society.

In that context, we have recommended a set of incremental but substantial reforms: to give the Boundary Commission a new duty to consider the electoral competitiveness of seats – that is, to tilt against the creation of safe seats – when boundaries are redrawn; charge the Electoral Commission and local government with significant new responsibilities to drive up voter registration; and to create a Democracy Commission to promote democratic renewal, both representative and participatory.

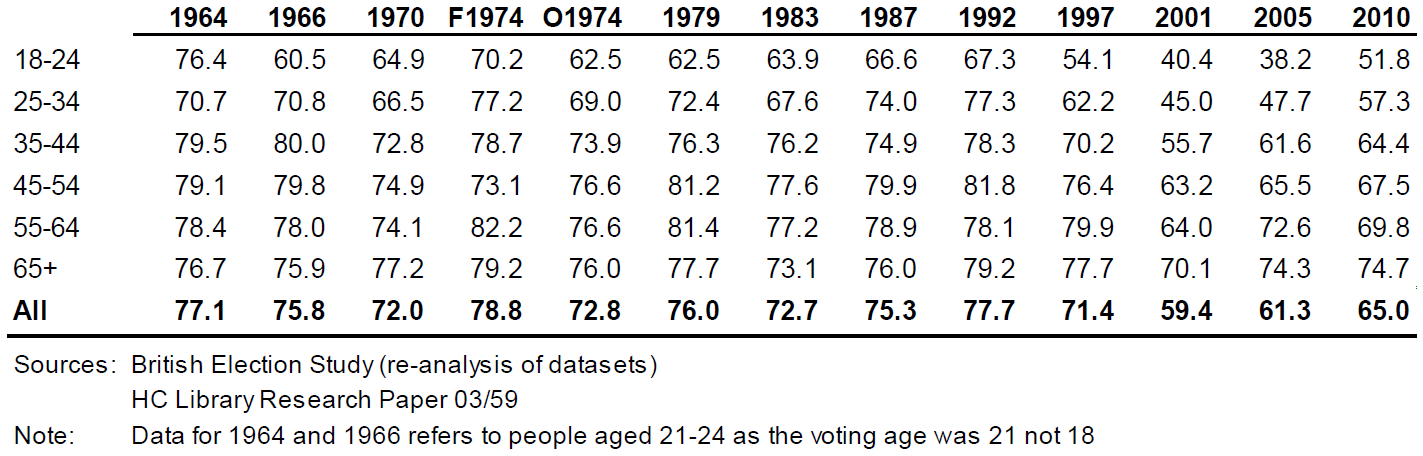

Most people are familiar with the inequality in turnout between the social classes. No less egregious is the inequality in turnout between the generations. This is now a major political cleavage, with hugely significant consequences. In the early 1960s, turnout rates differed little between young and old, but as the table below shows this gap has widened dramatically over the decades since, and for the 2015 general election it is estimated that the difference will be 35 percentage points (data from the British Election Study data is due to be published in October).

Figure 1: Estimated percentage turnout by age at general elections, 1964–2010

This is of particular consequence for the Labour party, since it has suffered huge losses among older voters: 47 per cent of the over-65s voted Conservative in 2015, a 5.5-point swing from Labour, who picked up only 23 per cent of this key section of the electorate. Labour won in every age-group up to those aged 55 and over. Yet its Russell Brand moment never arrived, and barring a major reform (such as compulsory voting for first-time voters), it never will.

Moreover, as Britain ages, the political clout of older generations will inevitably rise, as they become an increasingly larger slice of the electorate. Yet barely any of the Labour leadership discussions has touched on this fundamental point – which is especially glaring in light of George Osborne’s political acuity on the issue.

Indeed, there is an argument to be made that the ageing of northern European societies and the rise of political inequality between the generations has been an important contributory factor to the weakening of European social democracy. In the US, migration has replenished the population and helped to renew the Democrat coalition – Republicans cannot win elections with older white votes alone. In northern Europe, by contrast, migration and ageing have both worked to the disadvantage of social democrats, splintering working-class voting blocs and pulling politics towards the right.

So whether you care about electoral or constitutional reform or not, the political inequalities of ageing societies should matter. They have substantial political consequences.

This article was first published on Nick Pearce's blog