By Mark Hellowell | 22 September 2014

Northern cities are being promised major new infrastructure investment to help rebalance their economies. So will the chancellor make good on his warm words of support for the One North initiative and deliver £15bn in the Autumn Statement?

‘The powerhouse of London dominates more and more. And that’s not healthy for our economy. It’s not good for our country. We need a Northern Powerhouse too.’ So said George Osborne at a speech at Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry in June. Some cynics see belated interest in the North as an electoral overture for a Conservative Party that has few seats there. Regardless, leaders of the five largest northern cities – Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne and Sheffield – have taken the chancellor at his word and they are grasping the initiative.

Their One North plan incorporates a 25-year investment programme alongside a call for a substantial devolution of powers from the centre to enable that to happen. At the core of the initiative is a £15bn proposal to construct a high-speed trans-Pennine rail line running from Liverpool to Leeds and, ideally, to Hull on the east coast. The ambition is to improve transport links in the North to the extent that the region acts as a unified ‘cluster’, in which people, goods and ideas can move rapidly between cities as if in a single large urban centre.

If implemented, the plan would be genuinely transformational for this part of England – an area that has a population equal to that of the Netherlands but an economy only two-thirds as large. Movement between the big northern cities is currently a laborious process, especially on public transport. The train from Liverpool to Hull, a journey of 127 miles, takes over three hours – at an average speed of just 42mph. As a result, very few people actually make the journey. In contrast, passengers can get from Liverpool to London – a journey more than 100 miles farther – in about the same time, and HS2 will reduce that by nearly another hour.

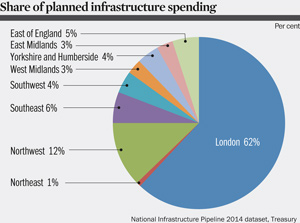

But if there are grounds for optimism after the chancellor’s speech, they are not to be found in the actions of this or any recent government. As think-tank IPPR North recently pointed out in its report, Transformational infrastructure for the North, there is a remarkable degree of London-centrism in the Treasury’s £483bn National Infrastructure Pipeline. Where public money is involved, the pipeline anticipates infrastructure spending in London of £5,425 per resident, compared to the next highest, the Northwest, on £1,248. The Northeast, however, sees only £223 per resident – or 1/25th of the value of investment in the capital. These disparities are not the result of some inescapable economic logic. They are the outcome of political choices, of cumulative decisions taken by governments over many years.

Reflecting on this experience, northern leaders believe that tackling disparities in investment must involve a number of wide-ranging changes to the political and technical processes through which infrastructure decisions are made. They are looking for Osborne to re-confirm his enthusiasm for the Northern Powerhouse concept in his Autumn Statement in December. The chancellor has hinted that will indeed be the case. The leaders make clear that, if he doesn’t deliver on this, there will be a political cost – and one that will be harder to bear for being six months before the general election.

‘Large infrastructure projects take political commitment – that’s what’s happened with Crossrail and the big London Underground investments,’ says Ed Cox, IPPR North’s director. ‘The chancellor has promised to make northern infrastructure the centrepiece of his autumn statement and he now needs to be held accountable for that. So we would expect to see support for the £15bn.’

So the politics matter. But there are also important technical impediments to change. In particular, the current approach to cost-benefit analysis, which determines how the Department of Transport prioritises capital investment projects, is often presented by ministers as a technocratic process that is free from political influence. Yet its structure has profound distributional consequences. The measurement of benefit, for example, favours richer areas with dense populations and busy transport routes. A project that reduces journey times on a busy commuter route presents readily measurable benefits in terms of the higher productivity of those commuters and the wages they can command.

The benefits of projects that focus on making poorer populations more affluent cannot be so easily measured.

Dieter Helm, of Oxford University, argues that increasing the productivity and earning power of identifiable service users – the ‘marginal benefit’ associated with investment – is not the correct way to assess the economic case for big public infrastructure projects. ‘A moment’s reflection indicates how weak such techniques are when it comes to deciding how much infrastructure to provide,’ he said. ‘Infrastructure typically comes in systems, not discrete bits. Choosing what sort and what level of infrastructure to supply is not a marginal decision. It is often about one system or another.’

With a programme like that envisaged for the trans-Pennine network, the issue at stake is whether there are economic benefits to creating a new urban cluster from the west to the east coast, not whether individual elements of the network make sense on their own. This network-level question is one that a conventional cost-benefit analysis cannot address.

Perhaps the fundamental problem for northern cities, however, is that there are schemes that may produce broad economic benefits that, in the current system, do not even attract enough interest from central government to get to the point of being appraised. For this reason, One North supporters are pushing for wide-ranging devolution of power over infrastructure policy – and transport in particular – to combined authorities and city regions.

IPPR North argues that what is needed is a Transport for London of the North – an entity with the power to take a strategic approach to investment across municipal boundaries and access the public and private capital required to invest on a strategic basis.

Is such a major shift in power achievable given the fragmented nature of governance in the area?

Lord Shipley, a Liberal Democrat peer and an adviser to the government on local growth, believes it is. He told Public Finance: ‘[Currently], you have a combined authority in Merseyside, you have one in Greater Manchester, you have one in South Yorkshire around Sheffield, you have one in the Leeds area and one in the Northeast – Northumberland, Durham and Tyne and Wear.

‘The big question is how all of those are enabled to grow, because one of the things that the chancellor, as I recall his speech, has said is that that the whole is less than the sum of the parts. But the whole should be greater than the sum of the parts, so there should be a big gain, and the question for me is how that is to be fulfilled.’

A key issue is how to access finance. Only the government can decide what sort of infrastructure systems the North needs, but the fiscal framework restricts capital budgets. After accounting for depreciation, public investment was 1.4% of GDP last year, down from 3.4% in the final year of the last decade. Danny Alexander, the chief secretary to the Treasury, may talk of the biggest programme of infrastructure development since the Victorian era, but in fact investment is lower in real terms than it has been for 12 years.

It is not clear what sources of alternative capital are available to realise One North’s ambitions, and the wider infrastructure requirements of the North, given current restrictions on public borrowing. Until 2012, the obvious solution would have been the private finance initiative, under which investors and construction companies sourced capital for investments that were off the public sector budget.

But PFI is now officially discouraged by the Treasury. Although its preferred approach, Private Finance 2, bears close resemblance to PFI, there appears to be little enthusiasm for moving ahead with this among government departments. The Priority School Building Programme, in which the new approach is being piloted, has reduced the scale of the privately financed component from an initial £2bn to just £700m.

The Ministry of Defence shifted its accommodation programme from private to public finance, as did the Department for Transport and the Crossrail rolling stock project. There is one PF2 project in the health sector – plans for a £352m Midland Metropolitan Hospital received Treasury approval in August – but there are concerns in Whitehall that the PF2 concept has not been proved.

Lord Shipley believes tax-increment financing – in effect, borrowing against the expected increases in future business rates attributable to enhanced infrastructure – could play a useful role, especially for transport infrastructure. ‘If the government is to expand TIF, the question is how you actually get the growth in property values that you want, because otherwise the borrowing becomes more difficult.’

Transferring risk from the centre is likely to result in better investment decisions but a higher cost of finance and more limited borrowing capacity. The trend at the moment, as seen in Scotland, is for parts of the UK to become more responsible for their own investment decisions, but finding the appropriate balance of investment risk between central and local government is a key issue.

‘I think the government will have to assist the North of England more in terms of underpinning its borrowing,’ said Shipley. ‘The private sector is very ready to invest in London and the Southeast, because the return is pretty quick and more than reasonable, but in other parts of the country it is more difficult for private investors to see a quick return for their money.’

Markets will not produce new trans-Pennine connections and other improvements to the transport networks of the North. Osborne’s plan seems to recognise this. But it is unclear if the political rhetoric will lead to political action after the general election, or turn out to be little more than an electoral sales pitch. Current disparities are, perhaps, illustrative of what many see as a wider trend in public policy, in which funding is channelled disproportionately towards the capital, and away from the poorer regions of the UK.

But devolution of infrastructure policy will meet with determined opponents. In early September, a CBI report called for the government to further centralise and depoliticise the process of infrastructure prioritisation. Similar themes are evident in the Labour-commissioned review by Sir John Armitt, former chair of the Olympic Delivery Authority, whose report last September called for an infrastructure commission to set priorities with freedom from short-termist political pressures.

This appears to be the last word in Labour Party policy on infrastructure policy, but there are clear tensions between this and the ambitions of the North to take on greater risk and responsibility over local investments. A big shift in economic policy may be needed to get the cities of the North moving again and northern leaders, including Manchester City council leader Sir Richard Leese and Liverpool mayor Joe Anderson, are pushing hard for that to occur. But whatever the pre-electoral rhetoric, it is clear that the political battle is far from won.

Mark Hellowell is a lecturer at the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh and an adviser to the Treasury Select Committee

Additional reporting by Richard Johnstone

This feature was first published in the October edition of Public Finance magazine