By Erik Britton | 1 September 2014

Government policies have put a rocket under over-inflated house prices while social housing’s share of the total stock has steadily fallen. So how do you rebalance the market?

Until the March 2013 Budget, the UK economy was in the doldrums. After the biggest recession on record, the recovery was weak at best. House prices were falling, the government’s finances were deteriorating, bank lending was contracting and inflation was uncomfortably high.

The Budget changed all that – specifically, the Help to Buy scheme announced by Chancellor George Osborne. The scheme has two planks: support for housebuilding and for homebuyers. The government would subsidise mortgages and finance for builders.

Since then, the UK has leapt from the bottom to the top of the league table of advanced economies in terms of its growth rates; house prices have accelerated into double-digits; bank lending has turned positive (at least to households); and inflation has slowed.

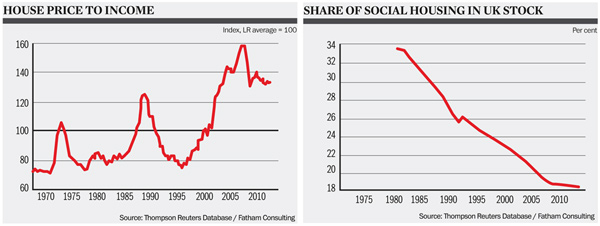

The UK is obsessed with housing. An unsustainable boom in house prices (and the debt that went with it) was the main cause of the banking crisis and therefore the recession. Although house prices fell back during the recession, they remained far in excess of fair value when Help to Buy was introduced. With Help to Buy, the government put a rocket under house prices which were already far too high. Our estimates suggest house prices need to fall by a further 20% to 30% relative to incomes to bring them back to fair value.

If the current momentum persists, the ratio will increase further – back towards the all-time peak it reached before the recession, or even beyond. We are still in a house-price bubble, and we are now inflating it even further.

Before the recession, stories abounded that purported to explain and justify the house price boom: things are different now… the UK is a small country with a limited supply of housing… there are more households now than there used to be, etc. Now those stories are being rehearsed again to explain why we need not worry about house prices, at least not yet. The most frequent excuse is a supposed shortage of supply, especially in London and the Southeast of England.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the UK suffers from a chronic shortage of houses. All political parties agree, so does the Bank of England and so (unsurprisingly) do the housebuilders. Universally acknowledged it may be; true, it is not. Housing stock per head has been flat, though at historic high levels, over the last decade. In 2012, for example, the UK population grew by 0.6%, as did the stock of housing.

But surely that can’t be true in London and the Southeast? House prices have certainly grown much more rapidly in London and the Southeast than in the rest of the UK. However, the ratio of house prices to incomes – the key metric – is no more extended in London and the Southeast than it is on average across the UK as a whole. House prices have grown more rapidly there because incomes have grown more rapidly. In fact, the degree of overvaluation is similar across all regions except Northern Ireland.

The supply of private housing has increased. Ever since the reforms of the 1980s, the share of social housing in the total housing stock has been falling gradually. So, while the stock of housing per head has been flat, the stock of private housing per head has been increasing – albeit less rapidly than it once was

Any asset price ought to reflect the future stream of income which that asset produces: in the case of housing, that income is rent. Rent measures the cost of purchasing housing services – shelter. If those housing services were really in short supply, then rents would increase relative to incomes. But the reverse is happening: rents are falling relative to incomes – and are lower now than at any time since the rent controls of the late 1970s.

The problem is not a shortage of housing, but cheap and subsidised housing credit. Although mortgage lending spreads are much higher than before the recession, monetary policy is so loose that a two-year fixed mortgage rate is now about 2.5%, close to its all-time low. And the government (through Help to Buy) is subsidising mortgage lending still further.

This country has never seen anything close to the support that is currently in place for house prices. The housing market is a key channel – perhaps the key channel – for the transmission of monetary policy, which has now joined forces with fiscal policy. Policy-makers are throwing everything they have at the housing market – and it is working.

It is working so well that concerns about a potential house-price bubble and the damage that could inflict on the banking sector and the wider economy have been expressed even in the hallowed halls of the Bank of England. Those concerns have not yet been reflected in the stance of monetary policy (and nor will they be in the near future) – but the newly aggrandised Bank now has other tools at its disposal.

Much has been made of the role of the Financial Policy Committee and its use of macro-prudential policy – restraints on the ability of banks to lend beyond certain key ratios that threaten financial stability. The FPC, we are assured, is keenly aware of the risks in the housing market and will act to mitigate them.

Unfortunately, such action as has so far been undertaken is far too little to make a significant difference. And the evidence from other countries that have implemented macro-prudential policy is salutary: Spain, Ireland and Canada were all early exponents of macro-prudential policy as a means to control the housing market. In Spain and Ireland, it did not work out well, to put it mildly. In Canada, house price and household debt-to-income ratios have grown continuously through the recession and to date, despite macro-prudential policies aimed at restraining them. The housing market correction in Canada is still to come.

Macro-prudential policy will not put a lid on the demand for housing while rates stay low and Help to Buy remains in place. In a tug of war with monetary and fiscal policy on one side and macro-prudential policy on the other, monetary and fiscal policy will win.

Monetary policy will remain exceptionally supportive into the medium term. Analysis from the Bank of England suggests that just a 200-basis-point increase in mortgage interest rates would drive housing market stress up to the levels it reached just before the biggest financial market crisis of all time.

That alone is probably sufficient reason for the Monetary Policy Committee to hold back on increasing interest rates more rapidly. But there is another side to the story: interest rates affect all parts of the economy, not just the housing market. Higher rates would drive up the value of sterling; increase firms’ costs and make it more difficult to export; reduce the income of households available for consumption; and penalise current consumption or investment in favour of savings.

The impact would be strongly negative for the economy as a whole, at a time when the recovery outside the housing sector is fragile. If rates were to rise enough to deflate the housing bubble, the impact on the wider economy would be dramatically negative – with a risk of an outright recession.

Our policy prescription is for fiscal policy to switch sides in the tug of war. If Help to Buy were abolished, the balance between loose monetary policy and slightly tighter macro-prudential policy would be more even – though monetary policy would probably still win. The way to redress the balance is for fiscal policy actively to reduce the demand for housing.

Measures such as capital gains tax on a principal residence, or on the value of that and other property; a land tax; or an increase in stamp duty could bring house prices back down to their fair value and reduce the burden of debt on the typical household, without damaging the wider economy too severely.

There would be other benefits too. If policy continues to incentivise lending for housing against all other forms of credit, then that is where the bulk of the UK’s financial resources will be devoted. Housing is a profoundly unproductive asset in a macroeconomic sense. Creating those incentives means creating an economy that is destined for low productivity and weak growth at best in the long term: a zombie economy.

Erik Britton, director at Fathom Consulting, is a keynote speaker at CIPFA’s Social Housing Conference in London on September 26

This feature was first published in the September edition of Public Finance magazine