By Paul Woods | 27 February 2014

The likelihood of some English councils becoming unviable has been increased by a funding system that favours the wealthiest parts of the country. To avoid a financial crisis, the government must rethink its approach

It is now clear following recent statements and letters from ministers and officials in the Department for Communities and Local Government that there has been a significant change in grant funding principles. Where these previously reflected differences in spending need and resource equalisation, there is now a focus on ‘incentivisation’.

This change in emphasis and approach has produced a grant settlement for 2014/15 and an illustrative settlement for 2015/16 that will have profound effects on the poorest areas of England. There are disproportionately higher cuts in grant and spending power for the most deprived areas of the country, while the wealthier, least deprived areas see a growth in spending power.

The cumulative impact of such cuts in spending power risks bringing closer the point in time when some councils will no longer be able to meet statutory responsibilities and, after reserves and assets are exhausted, become unviable.

As well as being hugely damaging to the people and communities directly involved, this could deplete the confidence and morale of citizens, staff and partners across the whole of local government.

The prospect of multiple council failures over the next parliament could lead to a wider and more general financial crisis that will be extremely difficult to rectify.

What is clear is that the incentives for housing and business growth that have been built into the new system can still be achieved while also delivering proportionate and fairer changes in funding that continue to recognise need and maintain resource equalisation. These objectives are not mutually exclusive. The disproportionate distribution, erosion of resource equalisation and reduced reflection of ‘needs’ are separate and specific decisions by the DCLG.

Disproportionate funding settlements also risk an increasing sense of injustice and division in the country that will challenge the fairness and sustainability of the new grant system. This could potentially lead to its early replacement – creating instability for all councils, with the risk of significant swings in the distribution of funding under different political administrations. Ideally a more independent funding process – perhaps overseen by a commission as suggested by CIPFA – would create a more stable and rational funding environment for councils.

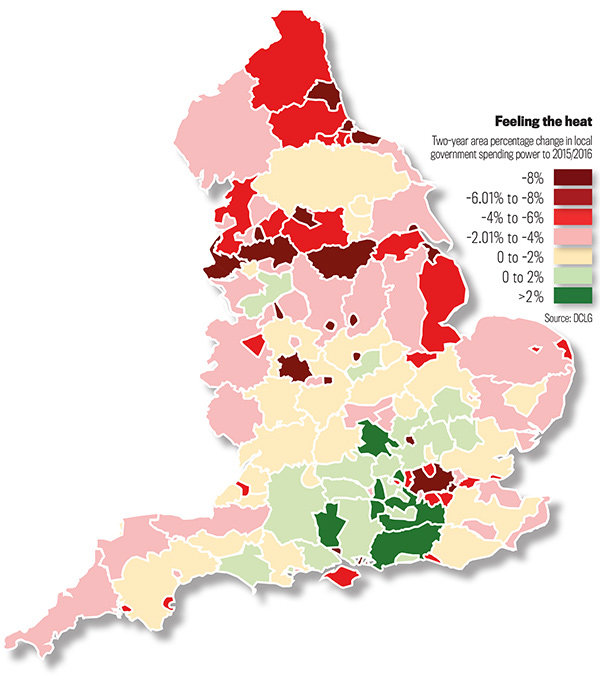

The differences in the change in spending power can be seen in Newcastle City Council’s ‘heatmap’ (above), which shows the percentage change in spending power over the next two years.

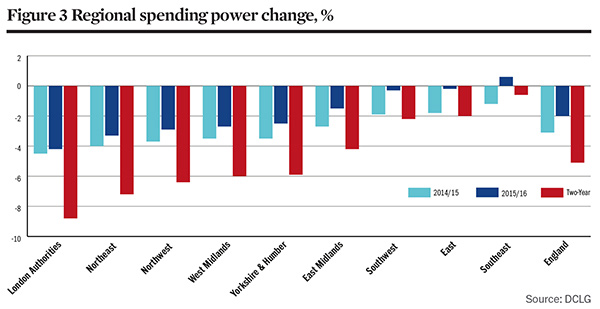

The pattern of spending power changes appears consistent, with the biggest percentage cuts in spending power in areas of the country facing the highest levels of deprivation and where there is most reliance on public funding. London, the Northeast and the Northwest are the worst affected. The smallest reductions or growth in spending power occur in areas that are generally the wealthiest and least deprived in the country, such as the East and Southeast.

The main reasons for the disproportionate change in spending power appear to be the decisions to erode council tax resource equalisation from 2014/15 onwards and changes to the way funding is top-sliced to pay for the New Homes Bonus, plus the hold-back to cover calls on the business rate safety net. Making the top-slice in a more equitable way, such as in proportion to the number of dwellings in an area, would reduce the disproportionate cut in funding and improve the fairness of the settlement.

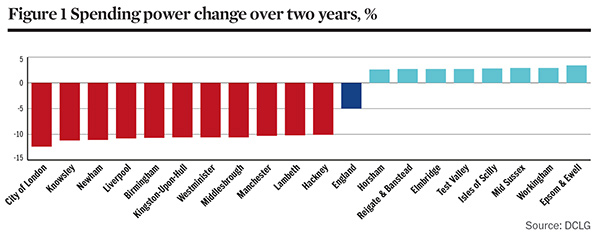

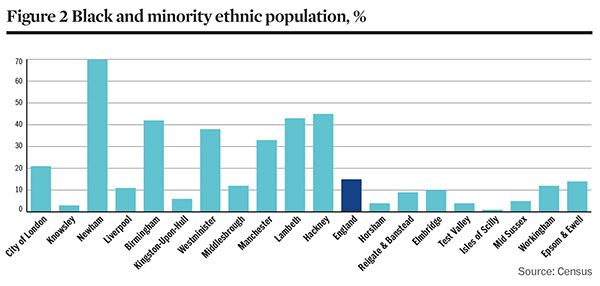

The impact of the disproportionate change in spending power on particular areas is shown in Figure 1, which highlights areas of the country with either cuts in spending power of more than -10% (twice the national average) or growth in spending power of over +2.5% for the next two years. Figure 2 shows the black and minority ethnic population proportion in each area.

The change at a regional level is shown in Figure 3. The two-year reduction in spending power in the Southeast of -0.6% contrasts sharply with the cuts in London and the northern regions of between -8.8% and -6.4%.

The disproportionate pattern of cuts challenges the continuing assertion that the grant settlement for 2014/15 is fair to all parts of the country. It runs contrary to the principles of fairness set out by Chancellor George Osborne in the 2010 Spending Review process.

He said then: ‘The government is determined to take decisions in a way that is in line with its values of freedom, fairness and responsibility. Therefore the government will… limit, as far as possible, the impact of reductions in spending on the poorest and most vulnerable in society, and on those regions heavily dependent on the public sector.’

Osborne added: ‘The government is committed to carrying out Britain’s unavoidable deficit reduction plan in a way that strengthens and unites the country. The Spending Review will be guided by the principles of freedom, fairness and responsibility, in order to demonstrate that we are all in this together. In light of its commitments to fairness and social mobility, the government will look closely at the effects of its decisions on different groups in society, especially the least well-off, and on different regions.’

The disproportionate impact of previous grant settlements has been highlighted by independent bodies – such as the Audit Commission, the National Audit Office and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. While the DCLG could have chosen to limit the impact, its decisions deepen the disproportionate effect on deprived areas to such a degree that there appears to be a statistically significant correlation between the largest cuts and areas with the highest black and minority ethnic populations.

The DCLG’s current assertion of fairness is based on a crude comparison of the absolute difference in spending power between councils such as the London Borough of Newham or Newcastle upon Tyne and Wokingham or Windsor. This is used to justify the fairness of grant settlements, with no regard to the considerable differences in circumstances or service pressures that the councils face. The independent report produced by the House of Commons Library for 2014/15 does not support assertions of fairness for the change in grant or spending power next year.

Looking ahead to 2015/16 and beyond, the disproportionate pattern of cuts is set to continue each year under the new grant system as the overall funding total for local government is cut. This is because it reflects a decision by the DCLG to allow the funding adjustment for resource equalisation to be cut significantly each year and by the way in which ‘top-slices’ and ‘hold-backs’ are made.

Modelling the impact of continuing changes in spending power in future years shows that the gap in spending power will not just close. In fact, it will cross over, resulting in the spending power of the most deprived councils being less than that of the least deprived councils by a significant margin.

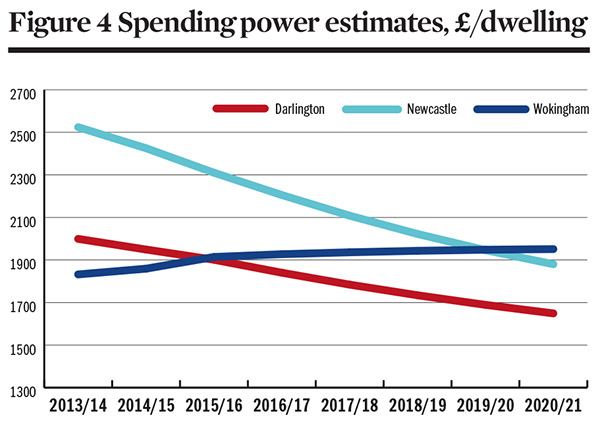

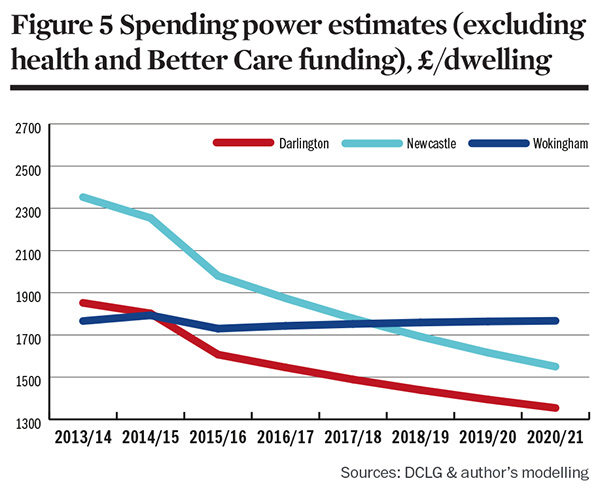

Figures 4 and 5 show the estimated effect on Wokingham, Newcastle and Darlington with and without public health and Better Care Funding and assuming similar annual levels of funding cuts to 2014/15. Darlington’s spending power falls below Wokingham’s in 2014/15 or 2015/16 and continues to fall. Newcastle’s spending power falls below Wokingham’s in 2017/18 or 2019/20 depending on the assumptions used and continues to fall.

All councils in the Northeast look likely to see their spending power fall below the spending power of the wealthiest councils despite having huge additional spending pressures. One of the main causes of this effect is the annual erosion of the council tax resource adjustment.

This represents another fundamental change – moving away from a funding principle that was applied to the council tax system in 1993/94 by the last Conservative government. This continued the principle of resource equalisation that had been accepted for decades after the 1948 Exchequer Equalisation Act.

However, Communities Secretary Eric Pickles did restore the council tax resource amount (CTRA) – to -£6.323bn in 2013/14. But its lack of visibility within general funding in 2014/15 means that it will receive no protection, unlike other funding items that are separately identified – such as the 2011/12 council tax freeze grant, which receives cash protection.

This means that it appears to be cut by -11.1% to -£5.620bn. Multiplying a negative amount by a -11.1% cut results in a cashback grant increase of £702m, with a higher cashback distributed towards the wealthiest councils in the country – those with the highest council tax bases. This has to be funded by a compensating additional cut of £702m to the most grant-dependent councils. Over the two years to 2015/16 the adjustment appears to be cut by -25% (-£1.58bn). The adjustment will be cut each year under the current approach.

This is also a very important change because it is the adjustment that compensates councils for different levels of student council tax exemptions. The significant erosion of this adjustment means that areas with above average numbers of student council tax exemptions will see a growing shortfall in their funding each year.

Having talked to colleagues in authorities around the country there was little recognition of the true scale of the change from the erosion of the council tax resource amount. This is mainly because unlike other changes (such as the council tax freeze grant) it was not adequately highlighted in the consultation. The distributional impact of this change could mean the loss of millions of pounds each year. For larger councils, such as Birmingham, this could amount to more than £13m next year and more than £30m by 2015/16.

DCLG officials were asked to show the impact of the change in November and of a simple alternative option that would have protected the adjustment at its cash level of -£6.323bn, in the same way that the 2011/12 council tax freeze grant was protected. They responded to my concerns by saying that the issue was sufficiently clear in their consultation proposals, and have yet to produce the illustrations requested.

Paul Woods is the director of resources at Newcastle City Council. This feature was first published in the March edition of Public Finance magazine