By Richard Johnstone | 1 March 2013

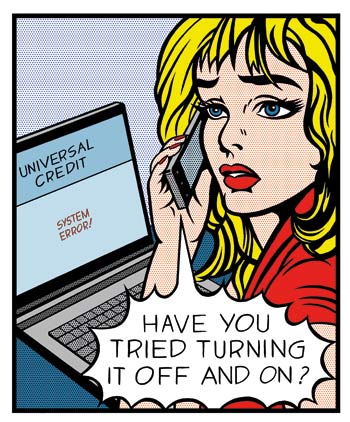

The government’s track record on IT projects is notoriously poor. So is the launch of the Universal Credit going to break the mould or repeat the big, costly failures of the past?

Trials begin next month on the biggest reform the UK benefits system has ever seen. Universal Credit will merge six existing payments into one, and be provided to an estimated 19 million claimants across the country.

As well as a huge change to the structure of benefits, it will also be the most significant information technology project undertaken by the coalition government. The challenge is immense, with the reform creating the nation’s first truly digital welfare service. It is intended that the vast majority of users will claim online and check payment details through a single account.

Concerns have already been raised that the scheme is too risky. Add in the UK government’s poor track record in IT projects, which have often come in late and over budget, and questions are being asked about whether Universal Credit can succeed.

The Public Accounts Committee certainly has its doubts. Ahead of April’s four pathfinder trials and a national rollout from October, it warned of ‘substantial risks’ due to dependence on the development of a new real-time IT system by Revenue & Customs. The botched introduction of previous flagship systems, such as the NHS National Programme for IT, did not inspire confidence, the MPs claimed.

Since the government came to power in 2010, it has attempted to make a fresh start. Its Information and communications technology strategy, published in March 2011, accepted that major IT projects had ‘a really bad name’. Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude pledged that the government’s ‘unenviable reputation for big, costly failures’ would change.

This strategy was followed last November by a cross-government Digital strategy and accompanying Digital efficiency report, which set out ambitions to make Whitehall ‘digital by default’. In addition to the Universal Credit, more than 650 government transactions are set to move online to cut administration costs. Services such as paying for car tax and applying for a passport currently cost £6bn–£9bn to run each year.

All services comprising more than 10,000 transactions annually now have a target to carry out 82% of their dealings online. Savings could total £1.8bn as a result, including £1.2bn by the end of the Comprehensive Spending Review period in 2014/15.

Maude’s pledge to create ‘modern, efficient, digital-by-default public services that are fit for the twenty-first century’ reflects a view that the UK has fallen behind in the use of technology in government. This is despite it being one of the first countries to embrace the IT revolution, at the turn of the millennium.

At the time, ministers were caught in a rush to put all documents and forms online, according to John Borras, a former director of technology in the Cabinet Office. But this proved to be a dead end, says Borras.

‘We did a couple of years and people weren’t using it. There was no benefit in printing off a form, and then filling it in and posting it to the department,’ he adds. Little thought had been given to how the citizen ‘wanted to deal with government’, he says.

More than a decade on and this remains a concern, particularly with Universal Credit. MPs on the Commons work and pensions select committee have warned that moving services online can make it difficult for vulnerable people without internet access to claim.

Borras agrees that a ‘digital by default’ Universal Credit is a ‘formidable challenge’, and warns that the government might need to take further action to ensure everyone can use the service. ‘You may get a financial return [by moving services online], but the question is whether we are delivering the needs of our customers. Personally I would question whether that’s the case.

‘Then you have to look at whether there’s another model by which you can deliver – computers in libraries and supermarkets, or it might need to be face to face.’

He says Revenue & Customs’ launch of online tax returns and payments between 1999 and 2004 was the first big success in digital public services. This showed what could be done by prioritising what the user wanted. More than 18 million transactions for corporation tax, Pay As You Earn and VAT are now completed online. But these appear to be all-too-rare successes.

Sir Ian Magee, a senior fellow at the Institute for Government, looked at the government’s use of IT in two reports, System error and System upgrade. Until 2005, he was second permanent secretary at the then Department for Constitutional Affairs and head of profession for operational delivery for the civil service. He has also been chief executive officer of the Information Technology Services Agency.

Public sector schemes face challenges that are as difficult as they get, Magee says. ‘There’s policy complexity, silo mentality between departments and question marks over understanding between business leaders – by that I mean permanent secretaries.’

This has led to problems such as costly over-specification of technology and late additions to already complex requirements, as well as a lack of consideration for the end user.

Those close to the NHS National Programme for IT provide similar testimony. Chris Exeter worked on its development as private secretary to the Department of Health’s director general of informatics. He says that the £11.4bn programme tried to ‘integrate different parts of the NHS through an infrastructure that had not existed up to that point’. However, it was ‘subject to policy creep’ from ministers and absorbed more functions as it progressed.

Exeter, who is now a senior fellow at the Institute of Global Health Innovation at Imperial College London, says that electronic booking of hospital appointments is a good example.

‘This was being delivered on time and on budget but, towards the end of that programme, the government introduced Choose and Book – enabling people, once they had been referred to a specialist, to decide which hospital they went to and therefore book the time. That’s a more advanced system, so there was an element of additional services and requirements being added.’

He calls the chopping and changing a ‘cultural problem in Whitehall rather than a technological problem’. So, have enough lessons been learnt to benefit schemes such as the Universal Credit? ‘My answer to that question is no, there hasn’t been. My fear is we are still looking at it from a single departmental perspective.’

Although there are plans to use data from a parallel Revenue & Customs system, he says it could be more effective to integrate them further, and reduce the risk of one or other going wrong. ‘It’s a massive programme, but it could be far better to think about linking together [the system] between benefits and Revenue & Customs.’

Magee agrees on the need to change how projects are managed. He particularly backs reforms to split major developments into smaller parts, with lessons shared between each – known as the ‘agile’ approach.

Full details will be published by the Cabinet Office soon, but the digital-by-default standards now require the use of ‘agile’ principles. This will include monthly updates based on feedback from actual users.

Officials at the Department for Work and Pensions insist Universal Credit is being developed to these standards. They call it an exemplar for how future schemes will look. Although a new policy, it makes use of many existing IT systems, and is ‘being developed and tested with real claimants to ensure that it works and is ready to go from day one,’ the department says.

However, Magee highlights a wider scepticism about whether government is learning the lessons, and also wonders whether civil servants are ready to change. ‘The government talks the right game as far as “agile” is concerned, but it needs to show examples of building around people’s requirements rather than what’s best for the executive.’ He adds: ‘The question is: are people geared up to doing that, or are they so imbued in the traditional way of delivery that they find it quite hard to adapt to utilisation of the user experience. That’s a big question.’

Magee believes that too often government itself doesn’t know how projects are progressing. This leads to ‘some really difficult questions’ about how senior civil servants keep developments like Universal Credit on track. ‘That applies to government more generally,’ he says. ‘Which is the major project that gets senior people’s attention? Is it, say, the West Coast rail line or the Universal Credit?’

One sign of change would be if the government stopped falling into crisis mode when technology misfired. ‘It’s all about seeing effective IT as part of a solution, rather than a problem that government has to confront from time to time, and swallow the pain of being roundly criticised by the media and the Public Accounts Committee,’ he says.

‘Government is great in a crisis, but some of these crises could be averted with better thinking up the line.’

This article first appeared in the March edition of Public Finance