By Nigel Keogh | 1 October 2011

Plans to increase staff pension contributions not only anger unions, they also threaten a clash between fairness to all and protecting the lower paid

Public services face widespread disruption on November 30, with unions undertaking a day of action over government plans to increase employee pension contributions. So what do the controversial changes actually entail?.

Public services face widespread disruption on November 30, with unions undertaking a day of action over government plans to increase employee pension contributions. So what do the controversial changes actually entail?.

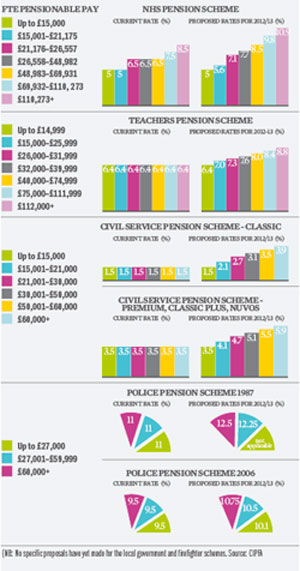

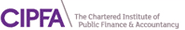

To protect lower earners, ministers propose that those earning under £15,000 should not pay any increase and those on £15,000–£21,000 should pay up to 0.6% extra in 2012/13 and no more than a 1.5 percentage point rise in total by 2014/15. There would also be a cap on the total increase for higher earners – 6 percentage points by 2014/15 (2.4% in 2012/13 on a pro-rata basis).

Such tiered contribution rates have previously been used only in the local government and NHS schemes. The result is that those on fairly modest levels of pay and above will pay progressively larger contributions to protect lower earners.

This might address concerns that higher contributions will speed up the exodus of low-paid workers from schemes. However, it also potentially clashes with the planned shift from final salary to career average benefits, one of the main recommendations of Lord Hutton’s Independent Public Service Pensions Commission.

In a final salary pension scheme, there is a strong case for tiered contributions, the Pensions Policy Institute has shown. Otherwise, people whose pay rises significantly towards their end of their careers end up getting a larger pension compared with what they have paid in than someone on a more steady earnings path. With tiered contributions, individuals pay a larger percentage of their salaries as their earnings rise, which goes some way towards ameliorating this imbalance.

However, this ‘high-flyer effect’ does not materialise in career average schemes. This is because pension accrues annually based on pensionable service and pensionable pay, which is revalued according to an agreed index annually until retirement. It is not based on salary at retirement. This establishes a direct link between the amount the individual contributes and the amount of pension they receive in any year.

For example, A and B are full-time employees in a career average pension scheme where pension accrues at 1/80 of pensionable pay per year. The employee contribution rate is 6%. A’s pensionable pay is £20,000 and so s/he accrues a pension entitlement of £250 in the year and pays contributions of £1,200. A therefore pays £4.80 per pound of pension. B’s pensionable pay is £40,000 and so s/he accrues a pension entitlement of £500 in the year and pays contributions of £2,400. The cost per pound of pension is again £4.80.

So B might end up with a pension twice that of A but will also have paid twice as much in contributions.

However, if a career average scheme is combined with tiered contributions, those earning over £21,000 might pay more per pound of pension than those earning less. If tiered rates were applied to the example above, say 6% at £20,000 and 8% at £40,000, the cost per pound of pension for B would rise to £6.40 with no extra pension benefit.

Whether tiered contributions survive the likely transition to career average pension schemes remains to be seen. A balance will need to be struck between meeting the potentially conflicting principles of fairness for all scheme members, which featured in Lord Hutton’s report, and protecting the lower paid from higher contributions.

Nigel Keogh is technical manager for pensions

at CIPFA

Plans to increase staff pension contributions not only anger unions, they also threaten a clash between fairness to all and protecting the lower paid

Public services face widespread disruption on November 30, with unions undertaking a day of action over government plans to increase employee pension contributions. So what do the controversial changes actually entail?.

Public services face widespread disruption on November 30, with unions undertaking a day of action over government plans to increase employee pension contributions. So what do the controversial changes actually entail?. To protect lower earners, ministers propose that those earning under £15,000 should not pay any increase and those on £15,000–£21,000 should pay up to 0.6% extra in 2012/13 and no more than a 1.5 percentage point rise in total by 2014/15. There would also be a cap on the total increase for higher earners – 6 percentage points by 2014/15 (2.4% in 2012/13 on a pro-rata basis).

Such tiered contribution rates have previously been used only in the local government and NHS schemes. The result is that those on fairly modest levels of pay and above will pay progressively larger contributions to protect lower earners.

This might address concerns that higher contributions will speed up the exodus of low-paid workers from schemes. However, it also potentially clashes with the planned shift from final salary to career average benefits, one of the main recommendations of Lord Hutton’s Independent Public Service Pensions Commission.

In a final salary pension scheme, there is a strong case for tiered contributions, the Pensions Policy Institute has shown. Otherwise, people whose pay rises significantly towards their end of their careers end up getting a larger pension compared with what they have paid in than someone on a more steady earnings path. With tiered contributions, individuals pay a larger percentage of their salaries as their earnings rise, which goes some way towards ameliorating this imbalance.

However, this ‘high-flyer effect’ does not materialise in career average schemes. This is because pension accrues annually based on pensionable service and pensionable pay, which is revalued according to an agreed index annually until retirement. It is not based on salary at retirement. This establishes a direct link between the amount the individual contributes and the amount of pension they receive in any year.

For example, A and B are full-time employees in a career average pension scheme where pension accrues at 1/80 of pensionable pay per year. The employee contribution rate is 6%. A’s pensionable pay is £20,000 and so s/he accrues a pension entitlement of £250 in the year and pays contributions of £1,200. A therefore pays £4.80 per pound of pension. B’s pensionable pay is £40,000 and so s/he accrues a pension entitlement of £500 in the year and pays contributions of £2,400. The cost per pound of pension is again £4.80.

So B might end up with a pension twice that of A but will also have paid twice as much in contributions.

However, if a career average scheme is combined with tiered contributions, those earning over £21,000 might pay more per pound of pension than those earning less. If tiered rates were applied to the example above, say 6% at £20,000 and 8% at £40,000, the cost per pound of pension for B would rise to £6.40 with no extra pension benefit.

Whether tiered contributions survive the likely transition to career average pension schemes remains to be seen. A balance will need to be struck between meeting the potentially conflicting principles of fairness for all scheme members, which featured in Lord Hutton’s report, and protecting the lower paid from higher contributions.

Nigel Keogh is technical manager for pensions

at CIPFA