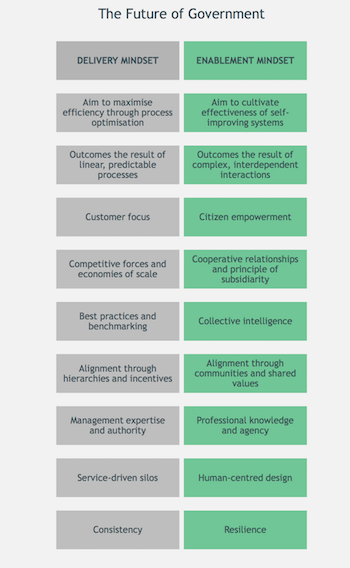

In recent decades, many governments around the world have embraced a service delivery mindset inspired by management practices from the private sector.

Having spent over 15 years working in the field of government performance myself, including a range of departments including the Prime Minister’s Office and the Delivery and Strategy Units, much of my career has involved adhering to this mindset, which holds that citizens can be thought of as customers of public services, and the same tools of process optimisation can be applied to a welfare service, for example as to a bank.

But now a different mindset is emerging in many innovative governments and public agencies around the world as they focus on enablement rather than delivery – an approach that aims to cultivate the conditions from which good solutions are more likely to emerge.

The enablement mindset is an alternative approach that encompasses three concepts; subsidiarity, localism and place.

Subsidiarity is the idea that decision-making rights should reside at the lowest possible level in a system. Recognising that much of the information about how to improve a system is embedded in the system itself, it follows that we should push authority to information and not the other way round. In public services this implies that, wherever possible, local actors should be empowered to shape solutions including frontline professionals such as teachers, doctors and social workers.

Localism stresses the importance of local accountability mechanisms and decision rights. Around the world, people have far greater trust in government bodies that are closer to them, because they have shorter accountability loops and can develop more locally appropriate solutions. Both representative democratic mechanisms and participatory mechanisms that open up deliberation and decision-making can flourish far more easily at the local level.

Place should be the dominant organising principle rather than hierarchical service silos. Place-based solutions start with an understanding of the assets, stakeholders and relationships in a locality and build from there, recognising that how success is defined and pursued might look very different in different places.

One example is the Buurtzorg model of community care in the Netherlands, which handed autonomy to healthcare workers supporting people in their own homes. This holistic approach allows small, self- managing teams of nurses to take responsibility for 50-60 patients in a neighbourhood and decide how best to organise themselves. There are no targets or best practices imposed from above, instead, the focus is solely on the needs of patients.

Under the previous delivery method of management costs had doubled and service quality declined, but with the new model of enablement far higher patient and staff satisfaction has been achieved, for no more cost. The Buurtzorg model has since been replicated internationally by teams in Sweden, Japan and the United States.

We might describe the delivery mindset as envisaging the state as a giant machine ready to be optimised. By contrast, the enablement mindset would view public systems more like a garden that requires cultivation rather than control. This makes a profound difference to how we conceptualise what government is trying to achieve and how it goes about it.

The concept of enablement has profound implications for those politicians and public servants sitting at the top of hierarchies with a mandate to improve outcomes. It could really be true that the less they control, manage and measure, the better the outcomes will be.

For example, large, centrally run programmes are unlikely to succeed when applied to complex systems. Even when deployed with the best of intentions, central programmes can quickly deteriorate into box-ticking exercises that lack the support of those who are essential to their success. They can also be costly to administer and frequently fail to deliver, even on their own terms.

Similarly, centrally set performance targets and KPIs imply that ‘the centre’ understands which outcomes are most important and that they can be measured by metrics alone rather than a more rounded evaluation of what is creating better outcomes for people. As well as disempowering lower levels of the system, there is mounting evidence that such targets, especially when linked to incentives, risk encouraging perverse behaviours such as creaming (focusing on the easiest cases), gaming (for example, lowering standards to improve pass rates) and data manipulation (such as the underreporting of unfavourable results).

This is not to argue against the value of data but rather that it should flow horizontally within a system, informing practice and improvement in situ rather than from on high. In this way, the true value of the information can be used to help services continuously improve.

We will be further exploring and debating the implications of enablement as part of our Future of Government project. Contact us at [email protected] if you work in the public sector or in government and would like to contribute your thoughts and reactions