Put down your “no more cuts” banners – austerity is ending.

So announced the Prime Minister in her speech to the Conservative Party Conference yesterday.

Calling time on austerity is sensible politics, and has been debated by conservatives since the 2017 election.

There are signs of public opinion moving towards favouring more spending (and the taxes to pay for it).

However, the PM has taken a risk as her statement will be thrown back at her by Labour every time evidence of ongoing spending restraint emerges.

Indeed that response has already started.

So, is austerity about to end? Well, it depends on how you define it of course.

Let’s run through four definitions to assess the state of austerity.

- The Deficit

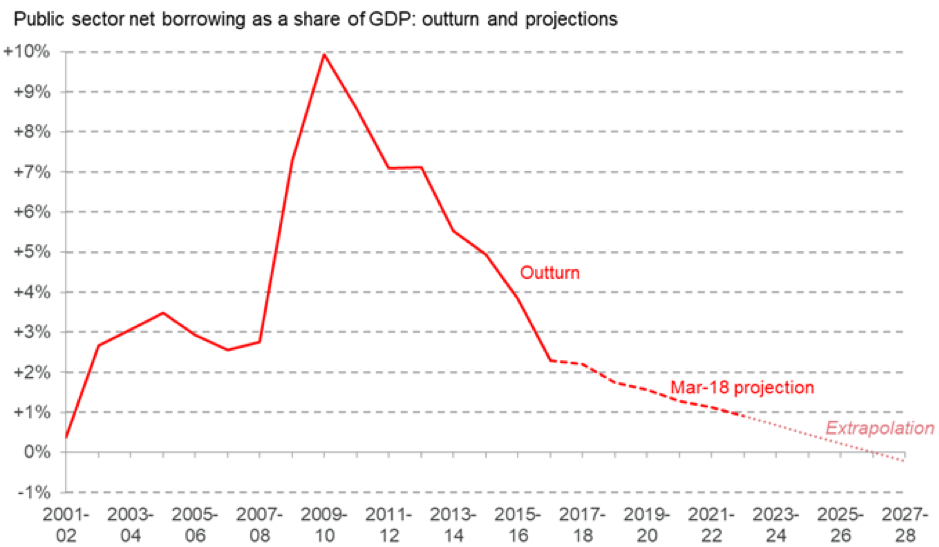

Austerity can mean many things, but is often most associated with the deficit.

The Treasury is formally committed to the long-held ambition to balance the budget – but achieving that is still a very long way off.

At the Spring Statement in March the government didn’t appear to be on track to reach that goal until 2027-28, with further tax rises and spending cuts required to get us there. That’s less an end to austerity and more a decade of it to go.

- Public Spending

For most people ending austerity is really about the programme of reductions in public spending – be that the cash local government has to spend or social security cuts – rather than the abstract issue of the government’s deficit.

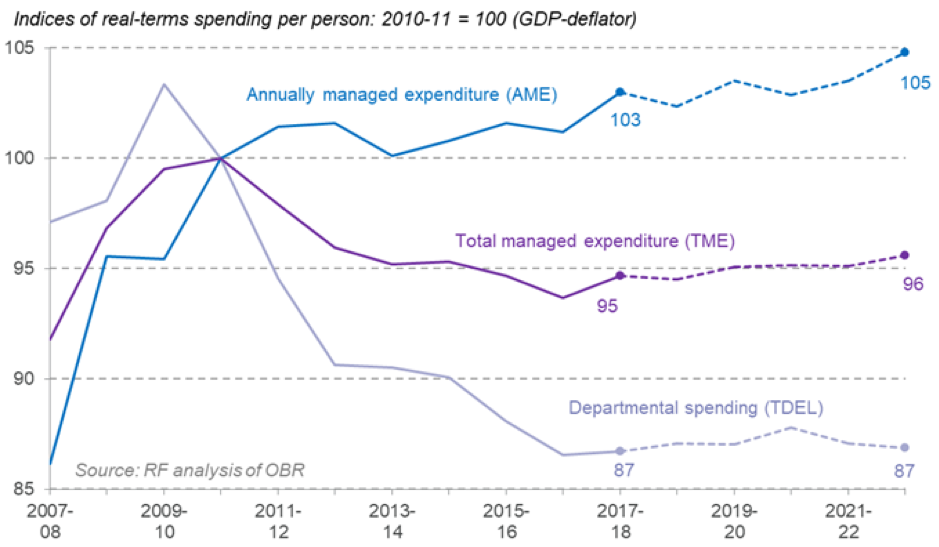

The latest public spending figures from the Spring Statement allow us to see what the government has pencilled in on that front. Here there might superficially be some better news for the ‘we’re ending austerity’ argument.

In terms of real-terms spending per person, overall government expenditure (TME) is already set to be rising slightly, having fallen by 5 per cent since 2010. Yes that small rise is driven entirely by increases in spending on debt interest and other non-public service areas (AME).

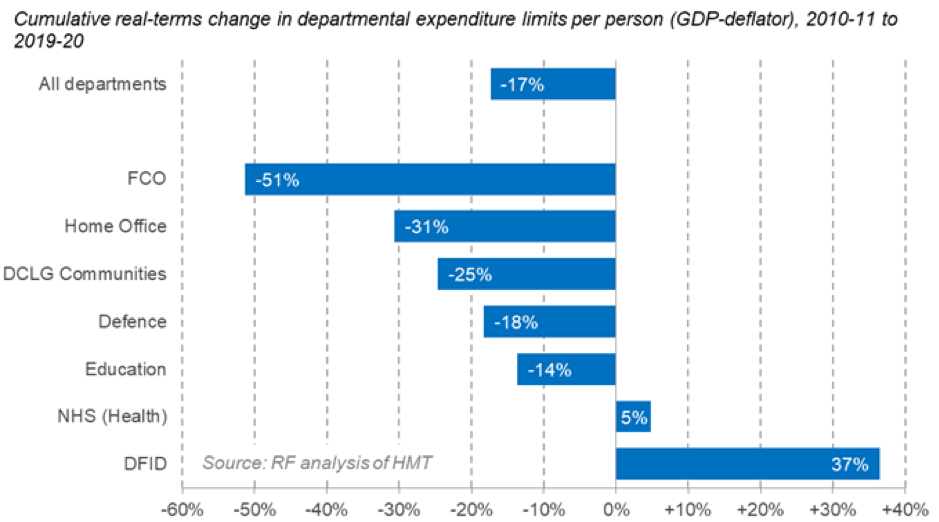

But even if we focus on departmental spending (DEL), the trajectory looks basically flat over the coming year. Not very austere you might think.

- Day-to-Day departmental spending

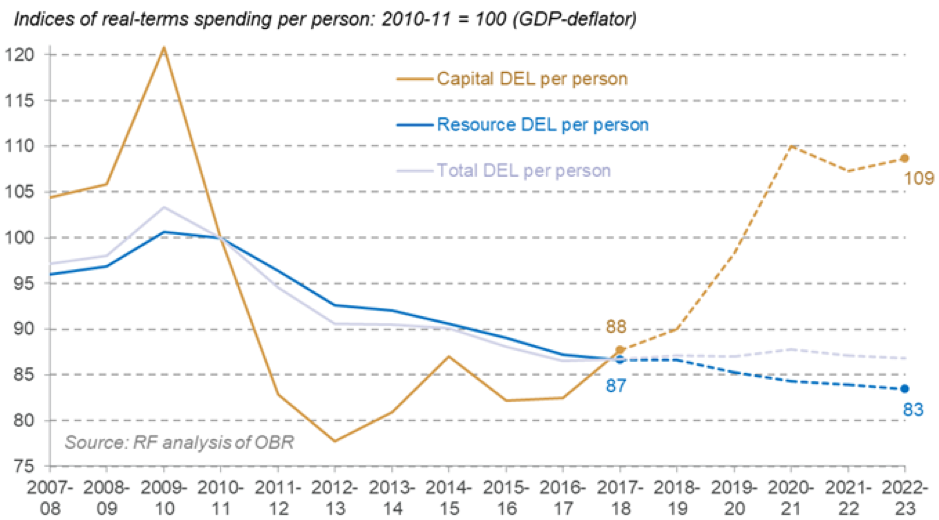

Although overall departmental spending is flat, this is being driven by a planned capital splurge that isn’t any use for running schools or hospitals on a day-to-day basis.

Focusing instead on resource spending (RDEL) – what we use to pay teachers’ and nurses’ salaries, run prisons and libraries – real spending per person is on course to fall further in the coming years.

To get a sense of the scale of the ongoing cuts to day to day departmental spending that are pencilled in we can ask what would it take to at least halt the slide in day-to-day departmental spending per person?

At the moment, such spending is set to fall from £4,806 per person in 2018-19 to £4,627 in 2022-23 (in 2017-18 prices).

Making up the difference would lifting the nominal RDEL budget in 2022-23 from a projected £342.2 billion to £355.4 billion.

- Benefits

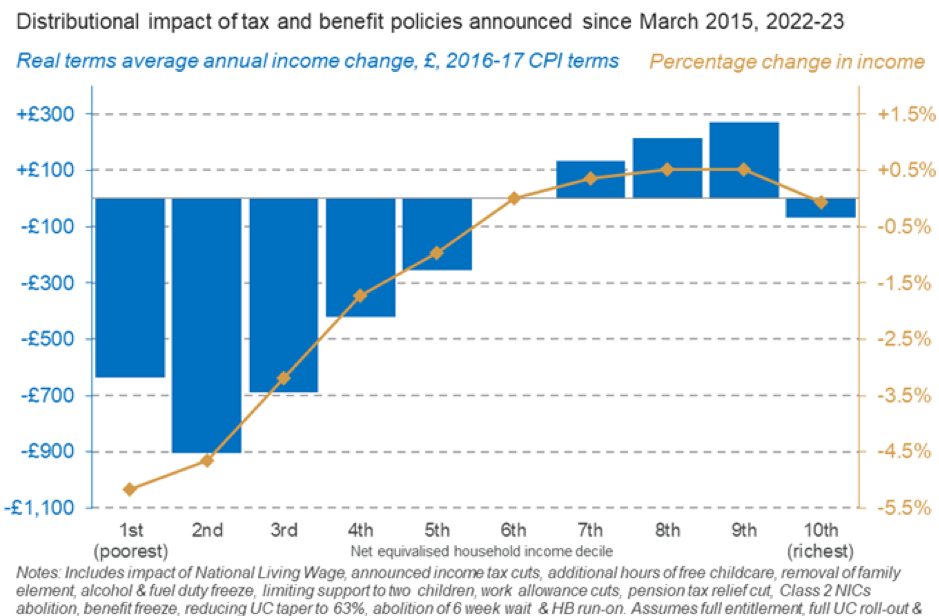

We must not forget that it’s hard to say austerity is over for ‘just about managing’ families while their benefits are being cut over the next few years.

Indeed the inflation figures in just a few weeks’ time will reveal the scale of the working age benefit freeze set for next April, a freeze that this year has meant an average loss of £315 for families with children.

Ultimately, as a think-tank focused on improving living standards, we’d define austerity by how it touches the lives of real people – from their local services to their benefit support.

That’s really how politicians should view it too.

And on that basis, austerity definitely isn’t over.

This doesn’t mean this speech means nothing when it comes to ending austerity.

Looking to the longer term, in many ways May’s speech itself was a sign that the political will necessary to maintain austerity is ebbing away.

After all it involved announcing scrapping a fuel duty rise (costing about a billion) and lifting the cap on councils' borrowing for housing (which means higher borrowing and debt).

So yes the speech has generally been well received, but it will have gone down very badly indeed in the Treasury.

What today really shows is that while austerity is here for a while longer, many Tories wish it just wasn’t.