What is the best way to divide up a pie? Should everyone get an equal slice? Or should those who contributed more to the making of the pie get a larger share? Do you incentivise the flabby by giving them just a sliver? And is it double helpings for those that have been running on empty?

How to cut up the local government funding pie is currently under review. The fair funding review, announced by then communities secretary Sajid Javid in December last year, will reassess and update spending needs and tax-raising capacities and set new baseline funding allocations.

An initial consultation closed in March, and specifics for a second consultation are expected to emerge in late spring or early summer next year ahead of the Spending Review, with transition to the new system from April 2020.

The review is more than a technical exercise and inevitably throws up some big existential questions about what local government should do and the how the tension between national standards and expectations and local discretion and delivery should be managed.

On 12 September, CIPFA and the Institute for Fiscal Studies invited a range of local government stakeholders to consider and unpick some of the issues coming out of this process.

IFS analysis

The IFS is currently running a major project, partly funded by CIPFA, into local government funding, looking at the impact of the fair funding review, as well as other changes to the finance system including plans for business rates retention and the impact of cuts on the sector.

David Phillips, associate director at the IFS, kicked off discussion with the observation that local government has had to adapt to some big financial changes, not least because of sharp reductions in grant.

He also highlighted a shift towards more financial incentives in the system, with measures such as the New Homes Bonus and plans for business rate retention introduced to encourage councils to support more house building and foster local economic growth. This is the context in which the fair funding review takes place.

Phillips’ colleague Tom Harris then led a detailed presentation on the current funding system and some of the possible effects of change. He pointed to considerable variation in assessed needs: one in ten local authorities have assessed needs at less than 85% of the national average, while one in ten have assessed needs greater than 125% of the national average, he said.

“High assessed needs are seen in inner London boroughs and other urban areas, low assessed needs in leafy suburbs and county councils.”

Poorer councils more dependent on government grant have seen larger falls in spending as government chose not to take needs fully into account when cutting grants. This begs the question: did this address previous unfairness to richer councils or unfairly penalise poorer councils?

“Assessing need is inherently subjective and requires political and expert judgement,” Harris said. “How do we ensure judgement is exercised transparently and subject to scrutiny?”

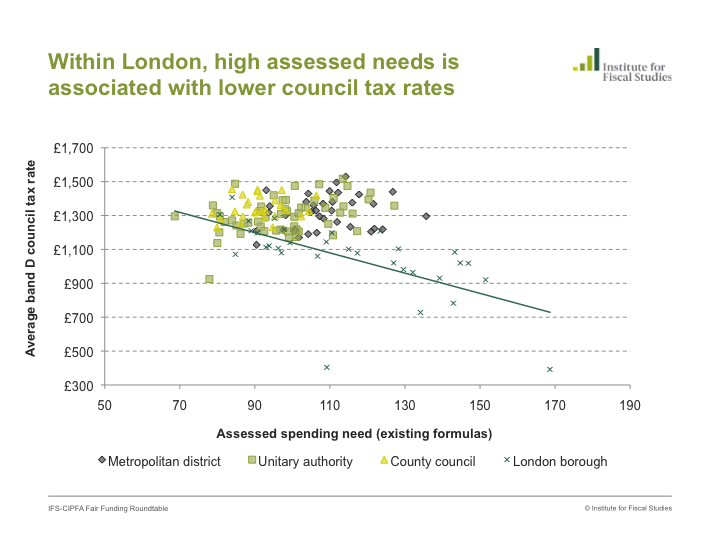

Councils’ tax revenues also differ significantly because of variation in the size of council tax bases (the number and value of properties) and in the rates applied by councils. In London, councils with higher tax bases and higher assessed needs tend to set lower tax rates (see graph below), but the IFS found no systematic relationship between bases and rates anywhere else in the country. Could this mean particular problems with the way the current system treats London boroughs?

“The government needs to think about how to bring together revenue raising capacity and spending needs in an overall funding system,” said Phillips.

“To what extent should the system offset differences?...If you don’t do much offsetting, councils have stronger incentives to tackle spending needs and boost revenue raising capacity. But councils with high needs or low revenue-raising capacity may struggle to fund the same range and quality of services as in more affluent parts of the country.”

“There’s a need for much more information to be published about how funding allocations have been determined to enable scrutiny.”

The fair funding review, Phillips said, offered an opportunity to make the local government funding system more simple and transparent. One of the “big takeaways” from the IFS’s research was to see transparency as a goal.

“We think there’s a need for much more information to be published about how funding allocations have been determined to enable scrutiny.

“It allows councils to hold government to account, and also allows voters to hold councils to account.

“It will allow critique of the system and it will also allow analysis of trends underneath the bonnet of the system.”

Phillips concluded by noting that the fair funding review was merely a debate about how to carve up the local government funding pie, not one about the size of the pie.

“When the pie is shrinking, what issues will that throw up?” he asked.

“Making sure that local authorities remain sustainable and continue to provide public services over the long term needs to be at the core of all these discussions,” said Joanne Pitt, CIPFA’s local government policy manager who facilitated the discussion.

Responding for the County Councils Network, head of policy and communications James Maker agreed that more transparency would be beneficial.

“Our members are very clear that to deliver a fair funding review there will be winners and losers but that shouldn’t be used a reason not to reassess need,” he told the discussion.

But the sector also needed a “bigger quantum” and the network would “push that message as much as possible”.

Simplicity and transparency

Giving a personal view, Aileen Murphie, director MHCLG and local government value for money at the National Audit Office, said funding systems should be kept as simple as possible. “Simplicity is all.”

She added that the fair funding review would help address some of the issues highlighted by the NAO about local government’s financial sustainability, but observed: “The variability is baked in now. The question then becomes how radical a transition is it? How much do you want to change things?

“The balance between incentive and grant is a difficult one and depends on what your political outlook is.”

“Making the system simpler is an important aim but we don’t want to sacrifice fairness to achieve this.”

Nicola Morton, head of local government finance at the Local Government Association, agreed that the current system was “exceptionally complex”.

“It is often said that there is a trade-off between simplicity and fairness. Making the system simpler is an important aim but we don’t want to sacrifice fairness to achieve this.

“But what is fair to one authority may not seem fair to another. This is particularly the case in the context of significant cuts in funding to local government since 2010 and a funding gap of £3.9bn in 2019-20.”

“There is also a difference between transparency and complexity. A lot can be done to improve the transparency of the system by explaining it in an easier-to-understand way.”

Philosophical questions

Local government is an “incomplete system”, observed Andy Theedom, a director at PwC, and limited, by central government, in how it can use the revenue it raises locally.

“What we need to think about instead is what are the key constraints that you might want to address to unlock system-wide change in a way that is politically acceptable, recognising there is basically a philosophical question about whether it is local determination or one-size-fits all?” he said.

“There are some incentives in the system, but there are loads of bars to stop genuine incentives.”

Paul Dossett, partner at Grant Thornton, agreed the fair funding discussion raised political and philosophical questions about the role and function of local government.

“Is it there to make decisions about what local people want and do things local people want or is it there just to redistribute government funding?” he asked.

Dossett added that many more incentives could be built into the system, such as tourist taxes, which would allow more local revenue raising.

“At the moment we’re in this strange hybrid where the government is talking about incentives, and there are some incentives in the system, but there are loads of bars to stop genuine incentives.”

Maker of the CCN cited the New Homes Bonus as something intended to incentive housing growth, but which had instead disrupted and destabilised the funding system, redistributing against need and away from upper tier authorities.

“MHCLG’s own analysis found it hadn’t incentivised housing growth and hadn’t been spent on the things it had intended to,” he said.

“You can’t have housing and business growth without transport infrastructure, schools, social care, all those things that make communities [and are governed and provided by upper tier authorities]. You have to look at how incentives work.”

Local government would “adapt to survive” ventured David Smith of EY. He cited councils establishing housing companies to build more affordable housing in their local area and secure a future council tax revenue stream.

“That’s adapting to survive… it’s going to change with the regulations and the landscape. The incentive is to keep people in the borough and generate council tax receipts for the future.”

The current funding system might not be perfect, but perhaps just needed adapting and not reinventing, Smith suggested.

Extreme cases

Some participants suggested that changes to funding allocation would not make very much difference to the most councils. Westminster, for example, is able to collect significant amounts of revenue from parking charges, however, this is not the case for most authorities.

Phillips said the IFS’s analysis had shown that changes to the funding formula affected councils at both end of the spectrum the most, while effects were fairly modest for the bulk of councils in the middle of the pack.

“How much should a system be designed that works for the extremes versus just getting it right for everyone else?” he asked.

“If we go for simplicity, that would probably work for the bulk of councils. Do you then need something special for the extremes?”

“What’s so unfair with the current system? Can we really boil it down and describe it?”

Theedom suggested that better outcomes could be secured by encouraging local public services to work more effectively together rather than by making minor adjustments to funding allocations.

“Fairness is about what does it feel like to be a user of local public services, rather than what does it feel like to have X pounds more or less.

“What’s so unfair with the current system? Can we really boil it down and describe it? Because if we can’t, we can’t solve the problem.”

View from Whitehall

However, Stuart Hoggan, deputy director, local government finance settlement, at MHCLG, said: “I don’t know why we’re having a discussion about whether the current system is up to scratch or not. There is a strong consensus that it’s clearly not.”

As part of the fair funding review, the government was “starting with a blank sheet of paper” and taking no element of the current system for granted, he said. Each element would have to “get over a hurdle” in order to prove its worth.

“I have no doubt that we could make the system more simple and more transparent,” Hoggan said. “There are natural limits to that and we shouldn’t seek to over-simplify but we can do better than the current formula.”

While the needs side could be simplified fairly easily, he acknowledged that the resource side was “more difficult” because council tax varies to such a degree between authorities.

Maximising data

The discussion also considered whether more use could be made of data. “Councils have plenty of data, or at least have access to plenty of data,” said Guy Clifton, head of local government advisory at Grant Thornton.

“But it’s not currently being used in the right way or maximised to its full potential.”

“If we are not measuring the right things, how can we hope to understand how we can resolve and improve things?”

He added that it was important to capture the right data.

“For example, The CIPFA accounting code doesn’t capture anything on older people falling over, but the costs associated with this across the public sector are significant,” Clifton said, adding that anti-social behaviour and substance misuse were other examples of major cost drivers for which public sector data is not easily accessible.

“If we are not measuring the right things, how can we hope to understand how we can resolve and improve things?”

Smith suggested more use could be potentially made of Big Data in assessing spending need and determining allocations.

“The systems don’t talk to one another, we know that, but if in local government you internally click on something that says ‘I’ve got another extreme adult social care case’, why can’t that go back to the centre and score or rank it to say ‘based on funding this year you’re going to need more for next year’.

“The point about Big Data and artificial intelligence is it learns from the past. After a few years you could have not a fair system but a perfect system.”

A perfect system might setting the bar a bit high, but there appears to be broad consensus that we can find a better way to slice the pie.