21 October 2005

The education white paper aims to complete the government's reforms by hugely extending parental choice and providing better schooling all round. But, asks Martin Bentham, will this latest upheaval do what it says on the tin?

In a few days' time, Ruth Kelly will stand at the Commons dispatch box to announce the details of the government's latest blueprint for the future of the nation's schools. The education secretary's long-awaited white paper is being billed as the final piece in the jigsaw of school transformation started by Labour in 1997. It will set out plans to give greater freedom to schools, improve standards in less successful institutions and increase the number of places in good schools.

New measures to improve classroom discipline will also be announced, along with a promise to give parents far greater information on how their children are performing as they progress through school. Kelly's aides say the aim is simple, but ambitious at the same time. 'It's about increasing the number of good schools and the number of places in good schools, providing more personalised teaching for pupils, giving better information to parents, and driving up standards as far as possible,' says one senior Whitehall official.

Prime Minister Tony Blair himself has described the purpose as being to 'escape the straitjacket of the traditional comprehensive school and embrace the idea of genuinely independent non-fee paying state schools'.

The vision might sound appealing but, even before publication of the white paper, the debate has already begun about whether the reality will be able to match the rhetoric. Among the questions being asked is: if schools are to be given greater freedom to set their own admissions policies, what will happen to the most challenging pupils – those who, to put it bluntly, no-one seems to want? Similarly, is there not a danger of a 'free for all' scramble among schools to recruit the best pupils, which will make wider planning of places almost impossible?

What, too, will be the role of the local education authority in future? Ministers have said that this will change from being a provider of education to being a 'commissioner' – but what will this mean in practice, and what will the consequences be for those who work in town halls now? Most importantly of all, will all the promised choice really deliver what parents and pupils want and need – good-quality education for all?

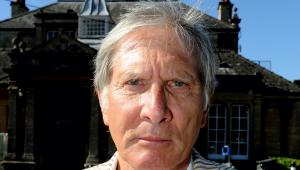

'The government is hoping that by having a variety of schools and allowing parents to choose, it can improve performance because pupils, and the money that goes with them, will go to schools that do well,' says Alan Smithers, professor of education at Buckingham University and one of the country's leading commentators on education. 'It's a theory that works very well in genuine markets, but the problem is that in a market some people get better deals than others and some miss out altogether, whereas in education everyone needs a good deal. The challenge that the white paper has to address is to show how diversity and choice can scale up to work not just in a few schools, but across the whole education system.'

The first plank of the government's strategy is to increase the number of good schools and, as ministers see it, to increase choice by ensuring that different types of school are available for parents to consider. Kelly and Blair have already set out much of what will be in the white paper on this subject in their recent speeches. The most controversial reform is, of course, the plan to open 200 city academies by 2010, backed by private sponsors and operating independently from the rest of the state system. The government insists that academies are successful, popular with parents and often provide hope in areas where previously there was little cause for optimism.

To emphasise their case, ministers point both to the results of a PricewaterhouseCoopers survey, published in June, which found that nine out of ten parents in city academies were satisfied with their child's education, and to recent figures showing an 8% rise at academies in the number of pupils obtaining five or more GCSEs at grade C or above. But the same statistics revealed that results had not improved at four out of the country's 14 new academies, while opponents argue that the improvements achieved elsewhere are principally the result of the extra investment received by the academies and their ability to attract pupils from outside the catchment of the schools they replace.

Equally significant in ministerial eyes, however, will be the continued growth in the number of specialist, faith and foundation schools. All but 200 schools are expected to be specialist institutions by next September, and changes that came into effect in August already make it easier for schools to have foundation status, and thus more scope to run their own affairs. More generally, greater financial 'freedoms and flexibilities' – as yet undefined – are also promised for all schools.

The prime minister made it clear what he wants last week: 'By the end of this third term, I want every school that wants to be, to be able to be an independent,

non-fee paying state school, with the freedom to innovate and develop in the way it wants and the way the parents of the school want, subject to certain common standards.'

In addition, the white paper will include provisions to make it easier for other providers – including groups of parents, educational charities and faith groups – to set up new schools. There will also be a purge on under-performing schools. The government has promised to introduce powers that will allow failing schools to be shut within one year.

'Coasting' schools – those that Ofsted inspectors say are failing to get the best out of their pupils – will also be targeted, particularly through an extension of 'federations', in which one high-performing school effectively takes over the running of one or more of its less successful neighbours. A proposal to give local authorities the power to force struggling schools to federate will be contained in the white paper.

The second, equally challenging, aspiration is to widen access to all these schools. The white paper will set out plans to make it easier for schools to expand and to push local authorities, where reluctant, into supporting such expansions.

Ministers say that federation will also play a part by spreading good practice from successful schools to their neighbours – hence increasing the number of places available at schools with high standards. But they accept that, whatever they do, there will still be competition for places at the most sought-after schools. Here the government's aim – as with universities – will be to increase the social mix of those gaining places, reducing 'selection by mortgage' and the current middle-class domination. The extent of this was highlighted earlier this month by the Sutton Trust, which found that only 3% of children attending the top 200 state schools qualified for free school meals, compared with a national average of 14.3% and 12.3% in the postcode areas of the schools.

One response expected in the white paper is a promise to provide better help and information for parents from poorer backgrounds to help them negotiate the complex school admissions process. 'Choice advisers', already used in the NHS, are one way in which this might happen. Also expected are school bus subsidies to help pupils whose parents cannot afford to live in expensive houses near good schools. But a nationwide 'banding' system, compelling each school to take fixed proportions of pupils in different ability bands, is unlikely, although officials concede that more schools might choose to use this method.

John Dunford, the general secretary of the Secondary Heads Association, questions whether the government's laudable aspirations can be met, fearing that the reforms will in fact result in a more socially segregated education system. He also argues that the entire white paper is unnecessary and will simply cause further distracting upheaval.

'The rhetoric about choice is false. Parents exercise a preference, they do not choose schools. The schools choose them, and if schools are getting greater freedom to set their admissions policies, then the danger is that we will get more polarisation, not less,' he says.

'Middle-class parents are always more adept at working their way through the admissions system and the only answer is to have schools working together to co-ordinate their admissions policies. I do not see anything in what the government is proposing at this stage that will improve things. We have had 20 education Bills in the past 20 years and what we really need is a year off. White papers normally lead to legislation, but if this does, it looks like being a Bill for the sake of it, not because it is needed.'

While the planned reforms might be unpopular with the education profession, ministers believe that parents will respond more enthusiastically, particularly to the promises of new 'micro-level' data that will track how pupils are performing year by year and a new complaints procedure, which will allow parents to report concerns to Ofsted.

Parents will also be urged to play their part in improving school discipline. Proposals for implementing the government's 'respect' agenda in schools will be unveiled, although calls for curbs on parents' right to appeal against school exclusions are thought to have been rejected, not least because of concern that disputes would then end up in court.

The final plank of the government's master plan is to transform the role of the local education authority. Town hall staff will be asked to act as 'advocates' for parents, putting pressure on under-performing schools, helping to bring in new providers where parents want new schools, and giving families assistance and information to help them gain places at the schools of their choice.

Graham Lane, the Local Government Association's former spokesman on education, says that while he accepts that the role of town halls in running the day-to-day business of schools is rightfully in the past, giving greater autonomy to schools, particularly over admissions policies, is a step too far.

He argues that in the rush to diversity, the most disadvantaged pupils could be left behind, with damaging consequences across education. He shares the view of Estelle Morris, the former education secretary, that ministers have mistakenly switched their focus to 'structures, not standards'. 'The problem with academies and diversity of provision is that if there are no levers to persuade these schools to have a broad intake, some won't do it. Will they discriminate, for instance, against pupils who are going to cost them more money, those with special needs or whose first language is not English, or against those who are under-achieving at 11 and will take more effort to teach? What, too, about those with social and behavioural problems?

Lane says: 'You can see that some other schools are going to be left with disproportionately more challenging pupils. I think that the result of this will be that it will be more difficult to raise standards in all schools, which is what local authorities seek to achieve.'

Indeed, perhaps the real test of whether the government will succeed in widening opportunity and raising standards will depend less on the legislation that emerges out of the white paper, and more on whether the drive to improve teaching and learning can continue to pay dividends.

It might well be that schemes such as the Black Pupils' Achievement Programme, which uses unspectacular but effective methods such as mentoring and greater parental involvement, combined with efforts of individual schools and teachers to tailor teaching more sharply on the needs of individual pupils, will ultimately be more important than the headline-grabbing battles over academies, faith schools and the like.

One thing appears clear, however. With education high on the government's agenda once more, and the prime minister determined to leave a lasting legacy before he finally stands down, the pace of change for schools, pupils and parents alike is likely only to increase over the coming years.

PFoct2005