The collapse of contracting giant Carillion one year ago sent shockwaves through both the private and public sectors.

It was Britain’s second largest construction company, and its liquidation has been named as the “largest ever in the UK”.

Creaking under the weight of £1.5bn in debts, Carillion’s demise, according to the National Audit Office, cost the public purse £148m as it picked up 420 abandoned public service contracts – in organisations ranging from schools and hospitals to prisons and the armed forces.

At the policy level, the Carillion story led to a thorough interrogation of the outsourcing model.

Outsourcing had grown in popularity since being kickstarted in the 1980s by then prime minister Margaret Thatcher, when local authorities were effectively forced to open inhouse services to the private sector to cut costs. From 2010, outsourcing was championed enthusiastically by Cabinet Office minister Francis Maude, whose Open Public Services white paper set out plans for a diverse marketplace for public services.

What a difference five or six years can make. MPs on the works and pensions, business, and public administration committees all made some trenchant comments. “The failure of Carillion reflects long-term failures of government understanding about the design, letting and management of contracts and outsourcing,” said the public administration committee in its report last summer.

The Carillion crisis gave opponents of outsourcing ammunition to launch a full-scale attack, and the government has had to shift position. Current Cabinet Office minister David Lidington has reaffirmed the government’s commitment to outsourcing, but intends to bring in a raft of new regulations to improve transparency and secure social value. A ‘living wills’ pilot is testing contingency arrangements in the event of another Carillion-style collapse.

Despite this, the debate rumbles on, especially with ongoing concerns over another large government contractor, Interserve.

This company’s troubles also became evident at the start of last year and it has been battling to stay afloat ever since. In December, it was seeking a second rescue deal as it struggled with £500m of debt.

Interserve has so far survived, with the government allowing it to continue to bid for public contracts, confident that it is not in the same dire financial situation as Carillion. But it will surely have spooked a local authority sector that looks like it was already starting to have second thoughts about outsourcing, as PF reported in March last year.

We highlighted Southwark council, which saved £4.35m after bringing its customer services back inhouse in 2013. Now, an exclusive PF investigation via freedom of information requests shines a light on council outsourcing over the past five financial years.

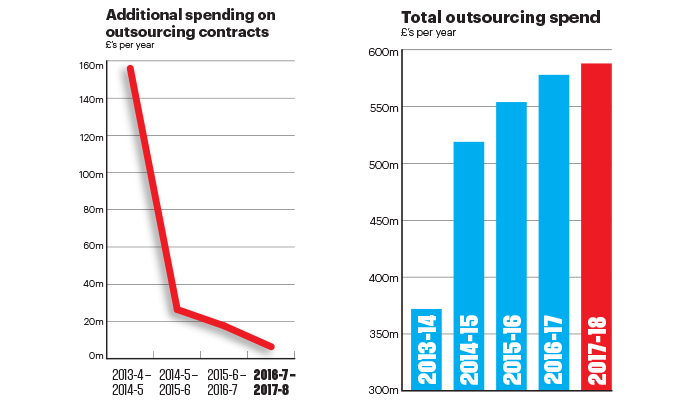

It reveals a dramatic slowdown in the amount of money local authorities have been spending [see graphs below]. Carillion’s collapse happened towards the end of the period that PF examined: was it the nail in the coffin for local government outsourcing?

FOI responses from 60 councils across England show a stark tailing off in the value of outsourced contracts. Where there was a 39% increase in the value of contracts between 2013-14 and 2014-15, this had almost flattened to just 1.6% between 2016-17 and 2017-18, with much smaller rises in the intervening years.

The most common services outsourced over the five-year period were waste management (17% of respondents), facilities maintenance and management (17%) and leisure services management (13%). A range of contracts were signed over the five-year period, from snow clearing to waste management to stray dog kennelling.

The most common services outsourced over the five-year period were waste management (17% of respondents), facilities maintenance and management (17%) and leisure services management (13%). A range of contracts were signed over the five-year period, from snow clearing to waste management to stray dog kennelling.

There were fewer similarities in the services councils chose to insource during that time, with authorities bringing back inhouse everything from cleaning services to highways maintenance to IT services.

PF analysis finds examples of councils that have made considerable savings by bringing services back inhouse.

East Riding of Yorkshire Council is one of the councils that put a figure on how much insourcing had saved it.

The local authority has reduced costs by £2m since 2013 after bringing back inhouse services like staff training, occupational health, payroll, IT and print and design. The council did not respond to questions from PF on why it made these decisions.

Derby City Council has also saved more than £1m in the past two years after bringing highways maintenance – a contract previously held by Carillion – back under council control. David Kinsey, head of highways, says: “We were confident we could run things more efficiently.”

He points out this was not because the council was unhappy with the service provided by the contractor. “It would be easy for me to sit here and say it was all because of the big bad contractor, but, actually, when we reflect on it, there were questions to be asked about whether we were writing the right contracts and whether we managed them effectively.”

Notably, not all contracts brought back under council control have been successful. Maidstone Borough Council brought a cafeteria within council property back inhouse at a cost of £220,000 between 2016 and 2018, but subsequently decided to re-outsource the management.

Notably, not all contracts brought back under council control have been successful. Maidstone Borough Council brought a cafeteria within council property back inhouse at a cost of £220,000 between 2016 and 2018, but subsequently decided to re-outsource the management.

Laurence Tricker, programme and projects manager at Maidstone, explains: “The decision was made based on a period of trading by the council during which losses were made. Since being contracted out, the café provides rental income and we have reduced our overall management costs.”

The membership organisation the Association for Public Service Excellence surveyed 208 senior local government officers in 2017, before the Carillion collapse. It found that 73% had or were in the process of considering insourcing a service, with 45% having already completed the process.

APSE’s head of communications, Mo Baines, says it was austerity that had driven “an increased need for efficiencies and improvements to service quality”.

She adds: “While major contract failures like the collapse of Carillion have focused minds, its contribution to the volume of insourcing in local government is of less significance than those contracts already being insourced by local councils.”

Mayor of Hackney Philip Glanville says his council has been on a 10-year journey to bring services back inhouse.

“We have seen that at almost every step you get a more coordinated response, save money, create better services and improve terms and conditions for the workforce.”

Between 2010 and 2014, the council brought back inhouse its recycling services, saving £600,000. It also took back control of its housing management service, reducing its costs by £300,000.

Matt Dykes, senior policy officer at the TUC, believes outsourcing has had its day. “There has been a growing trend for taking services back inhouse,” he explains. “Someone might suggest that we have reached peak outsourcing – there’s not much else now that can be externalised, and councils are down to core services only.”

Colin Haslam, professor of accounting and finance at Queen Mary University of London, agrees that local authority outsourcing has reached its peak.

Many councils had already started the process of “remunicipalisation” as he calls it – the localised provision of services.

Haslam believes the Carillion collapse is likely to mean more local authorities will bring services back inhouse, because of “an increasing risk in relation to the large corporate outsourcers, like Capita, Serco, G4S and Carillion”.

Outsourcing commentator John Tizard also agrees that Carillion’s legacy is likely to be muted local authority interest in outsourcing. “There have been some very high-profile failures in outsourcing, which has made many in the public sector – not least local government – question [its] usefulness.”

Tizard tells PF that the backslide in outsourcing is partly because of the lack of financial flexibility the model offers.

“In a period of tightening budgets, austerity and uncertainty, it is increasingly recognised that long-term contracts, which lock up sizable parts of your budget, further reduce financial flexibility and consequently the ability to protect frontline services that are not outsourced,” he explains.

A survey by the New Local Government Network from October last year suggests that Carillion has “dented public confidence in partnership arrangements”.

‘To cope with financial and demand pressures, councils are increasingly finding they need more flexibility and direct control over services’

Jessica Studdert, NLGN

NLGN’s poll of nearly 200 council leaders found that 39% wanted to outsource less over the next two years, compared with 15% who were looking to outsource more.

Jessica Studdert, deputy director of NLGN, echoes Tizard. “To cope with financial and demand pressures, councils are increasingly finding they need more flexibility and direct control over services – outsourced contracts tend to be long-term and can be unresponsive to changing circumstances,” she tells PF.

With no sign of financial pressures on councils easing, it could be easy to see why long-term and costly contracts with third parties would appear less attractive.

It is not just the local government sector’s views on outsourcing that might have been damaged over the past year.

Haslam claims private providers have become “increasingly defensive about taking on any further contracts, and are even handing them back”. Private contractors often view government contracts as too “onerous”, pushing them into loss-making positions, he suggests.

Tizard agrees that the private sector, too, is re-evaluating its position in a post-Carillion world.

“The likelihood is that they will increase their risk premium in their charges – I think many contractors will now be looking for a better return and therefore higher charges,” he predicts.

Kerry Hallard, chief executive of the Global Sourcing Association, an industry group, believes local government outsourcing should continue and that Carillion’s failure was not a result of this method of service provision. “Carillion wasn’t an outsourcing failure. Carillion was a corporate governance failure,” she tells PF.

Hallard expresses disdain for the “anti-outsourcing rhetoric” that followed Carillion’s liquidation, including government comments. “There’s no positive communication that comes from government, it is just obsessed with kicking rather than applauding its service providers,” she says.

But Hallard concedes that outsourcing is not always effective and that there is scope for change. “Outsourcing shouldn’t be focused just on driving out cost any more – that’s old school,” she claims.

Instead, she believes greater efforts should be made to bring SMEs into the fold, with fewer contracts going to the small number of big players.

In Hackney, Glanville agrees there needs to be greater consideration of SMEs in the government’s portfolio of contractors.

“Too often, big companies are going through the motions and delivering poor-quality services,” he tells PF.

Walter Akers, partner at consultancy RSM UK, explains why local authorities might prefer larger contractors: “There is a bias towards larger organisations, because they score better on risk and in the procurement process because they’ve got scale, they’ve got strong balance sheets – they’ve got experience.”

He also believes Carillion should be a wake-up call for councils when entering into contracts with large private organisations. “Councils think they can continue operating the way they always have after they’ve signed these big commercial deals, and experience shows they can’t. That’s where they end up spending more money longer term than if they kept services inhouse,” he tells PF. Councils should be more savvy in their contract management, he explains.

‘We have seen that at almost every step you get a more coordinated response, save money, create better services and improve terms and conditions for the workforce’

Philip Glanville, mayor of Hackney

Akers also points out that, often, local authorities outsource a service to a large organisation that does not necessarily have better skills. “Why was Carillion – primarily a construction firm – running libraries and providing school meals? It’s like going to an Italian restaurant and ordering a curry,” he suggests.

At the TUC, Dykes predicts that more council insourcing is to come. “It won’t change quickly, because you have had 30 years of this mindset and culture, and there will be long-term contracts that may be very difficult to get out of,” he says. “But things are changing already.”

Tizard tells PF: “The current Conservative government has said it sees outsourcing as the principal model for service delivery, but local government is perhaps more sophisticated, and local authorities led by Tories and Labour are all questioning outsourcing,” he says.

PF’s FOI research shows that 60 councils in 2017-18 still contracted out £588m of services. But Studdert says confidence in outsourcing has been shaken and notes a declining appetite among councils.

She adds: “That doesn’t mean an end to the role of the private sector in public provision altogether. It means that future partnerships need to be much more clearly built around the overriding imperative to drive deep social impact with public spend.

“If partnerships are built on a greater sense of shared endeavour and long-term value creation, this should recognise the innate strengths of each and absolute clarity of roles.”

Back to the source

Back to the source

Margaret Thatcher started an increase in public sector outsourcing when she brought in compulsory competitive tendering in 1980.

This effectively forced local authorities to open up inhouse services to private competition in an effort to cut costs. It was initially introduced for construction, maintenance and highways work by the 1980 Local Government, Planning and Land Act.

The policy was subsequently repackaged under New Labour. After winning the 1997 election, Tony Blair’s government replaced CCT with best value, forcing councils to look at outsourcing services, although the policy was also intended to consider quality alongside cost.

Further outsourcing was encouraged in the 2011 Open Public Services white paper introduced by the coalition government. This suggested that public services should be open to a range of providers – public, private and third sector – with control decentralised to the lowest possible level.