The Office for National Statistics has recently released its statistics on regional taxation and spending, and much has been made of the differences in revenue raised in different regions of the UK.

The Financial Times went so far as to suggest that London and the South East of England ‘subsidise’ the rest of the UK. There is little that should surprise us in these figures, however alarmingly portrayed.

The whole purpose of a progressive tax system is that some parts of the economy support and protect others. If the richest firms and individuals choose to congregate in one small corner of the nation then this will be the result.

This intuition is borne out when you drill down into the statistics.

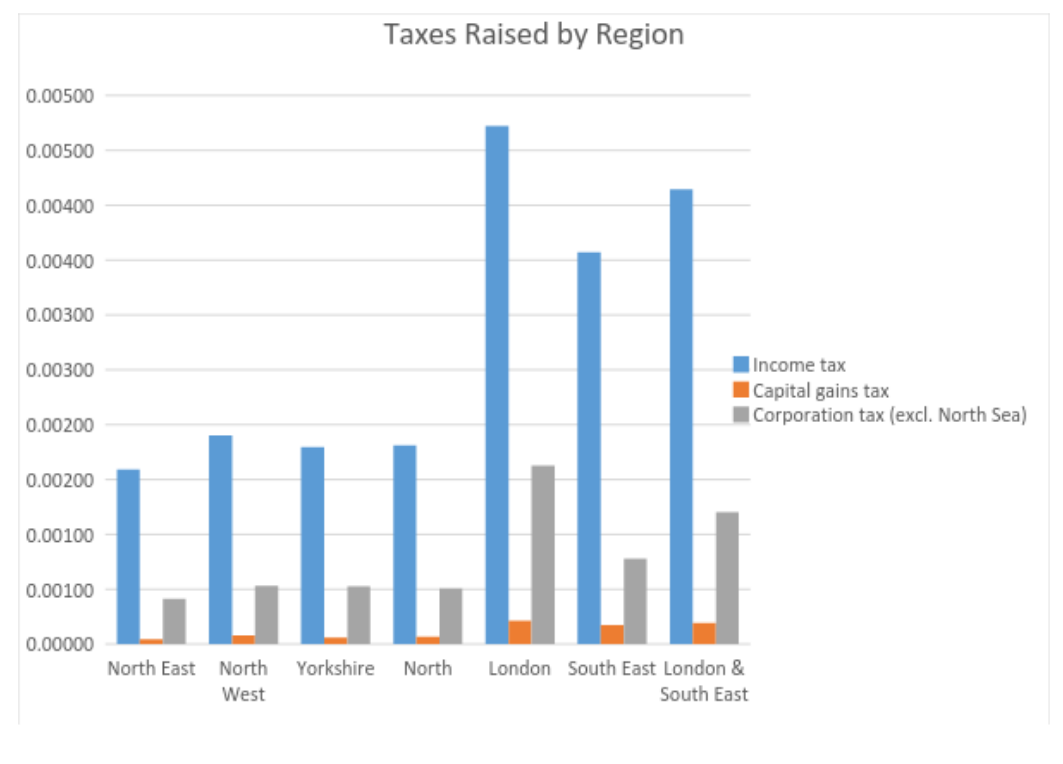

London and the South East pay more income tax, more capital gains tax, more corporation tax, more national insurance, and more of a variety of other smaller taxes [see the first graph below].

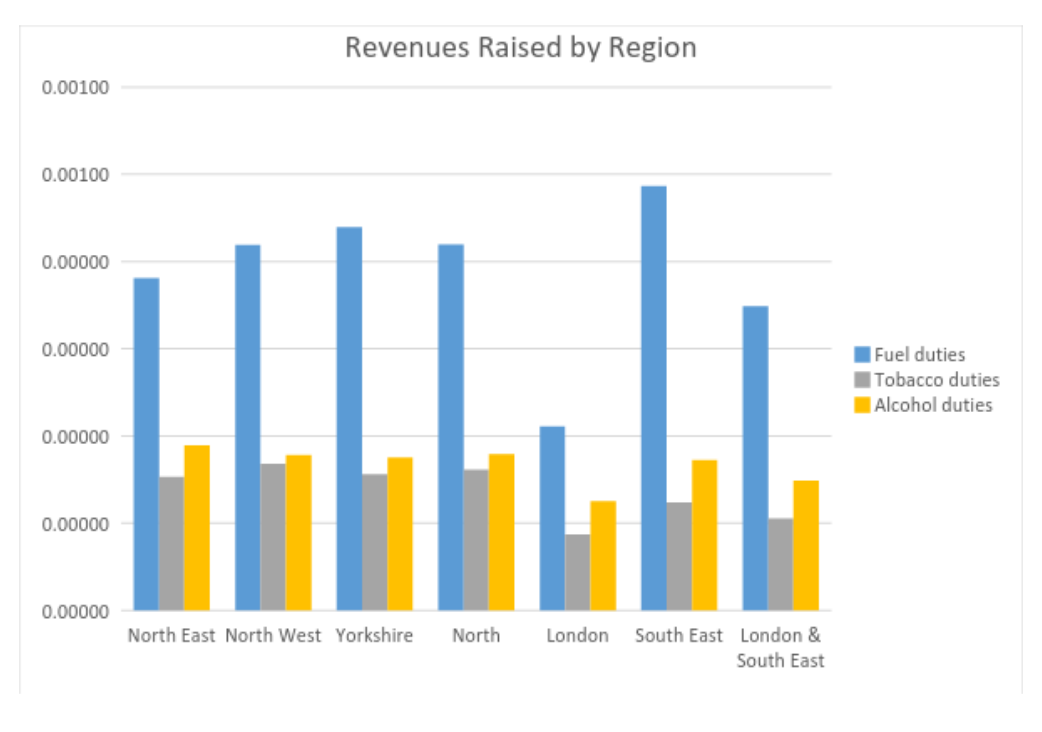

The North, on the other hand, pays more fuel and vehicle excise duties, more tobacco and alcohol duties, and more betting and gambling duty [see the second graph].

This is clearly because most large companies – not least financial services – are centred in the capital.

This has nothing to do with Londoners ‘subsidising’ the rest of the country – it has arisen out of decades of proactive policy that has been designed to expand London’s economy at the expense of the rest of the country.

If those same policies had been focused on Manchester, then things would be very different.

The statistics on fuel and vehicle excise duty also support this point.

Because the North has received so little transport investment in previous years – IPPR North’s research shows a £1,500 per capita gap in public investment in transport between London and the North – the public transport system is not nearly as developed as London’s, which creates its own barriers to greater private sector investment.

The other taxes are clearly correlated with the high levels of deprivation found in many areas of the North. These things are not inevitable – they have resulted from a London-centric policy agenda.

But the most concerning thing about this narrative is not just that it ignores these points, it is that the subtext reads ‘industrious southerners bankroll lazy northerners’. You can find similar versions of this narrative all around the world – in Europe it’s the hard-working Germans subsidising profligate Greeks, and in the USA it’s the brilliant North Westerners supporting the dull South.

But in each of these cases, there are both historical and more proximate reasons for the alleged ‘backwardness’ of one party.

Southern European economies were later to modernise than Northern ones, and have their growth has been stalled by the Euro, which gives Germany incredibly favourable terms of trade at the expense of damaging the competitiveness of southern European exports.

In the US, the South is still grappling with the legacy of slavery and segregation that defined all of its social, political, and economic life until as late as the 1960s.

The narrative of Northern ‘backwardness’ in the UK similarly serves to obscure the historical relationship between North and South, as well as propping up a deeply unjust status quo.

The UK’s regional disparities have grown significantly since the 1980s when a combination of political and economic forces transformed the global economy. As Northern industry floundered, power was systematically transferred to a new financial elite in the City of London.

But there is a governance problem too. Outside London and the devolved nations, there just aren’t the decision-making bodies with the autonomy to mobilise the appropriate local players, institutions, knowledge and capital to respond to wave upon wave of global change.

This is not just a ‘leadership’ problem, England is almost unique in its absence of any regional tier for strategic economic planning, apart from London.

It is all too easy to forget that the North-South divide has resulted from proactive policy decisions made by central government that favour the South at the expense of the North.

But just as policy decisions gave rise to this situation, they can also reverse it.

Central government must commit to investing in the long-term productive capacity of the North’s economy. It must invest in infrastructure, education, and public services. It must provide a proactive, place-based industrial strategy that allows the North to take back its place as one of the world’s foremost exporters of manufactured goods.

It must commit to regional institutions and real devolution to allow Northerners to take charge of their own destinies.

The only way to rebalance the UK’s grossly unequal economy is to support the regions to support themselves. The North’s natural energy, industry and independence will do the rest.

Grace Blakeley is speaking at the CIPFA conference on Wednesday next week.